[Image: Recording a landscape; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

[Image: Recording a landscape; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

Last winter, Past Horizons Archaeology ran some remarkable photos from a site in NW Russia, close to the border with Norway, where more than a thousands petroglyphs have been discovered carved into the horizontal surface of the local bedrock.

Most of the site had been buried under 5,000 years’ worth of mud, soil, and plant roots, and was only recently cleared by Jan Magne Gjerde, who otherwise works as a project manager at Norway’s Tromsø University Museum.

[Image: The team looks down at the earth they will soon record; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

[Image: The team looks down at the earth they will soon record; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

“In the summer of 2005,” we read, “Gjerde drove more than 1000 kilometres east to Lake Kanozero,” where the glyphs are located.

“Together with Russian colleagues he discovered what he calls some of the world’s oldest animated cartoons.” The glyphs, in other words, constituted a narrative—in this case, of a bear hunt. The sprawling series of images depict “a hunter who is heading uphill on skis and tracking a bear. The ski tracks are just as one would expect for someone going up a slope with a good distance between the strides. The hunter then gets his feet together, skis down a slope, stops, removes his skis, takes four steps—and plunges his spear into the bear.”

Indeed, “The figures depicted in the Lake Kanozero rock carvings include moose, boats, whales, humans, harpoon lines, beavers and all kinds of other ordinary and extraordinary images and scenes from the distant past.”

[Image: The petroglyphs; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

[Image: The petroglyphs; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

Interestingly, though, “Boats represent one of the most popular motifs in the rock art of Kanozero; they form 16% of all figures,” historians E.M. Kolpakov and V.Y. Shumkin explain in a paper published in Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia.

[Image: Boat glyphs from Lake Kanozero, courtesy of Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia].

[Image: Boat glyphs from Lake Kanozero, courtesy of Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia].

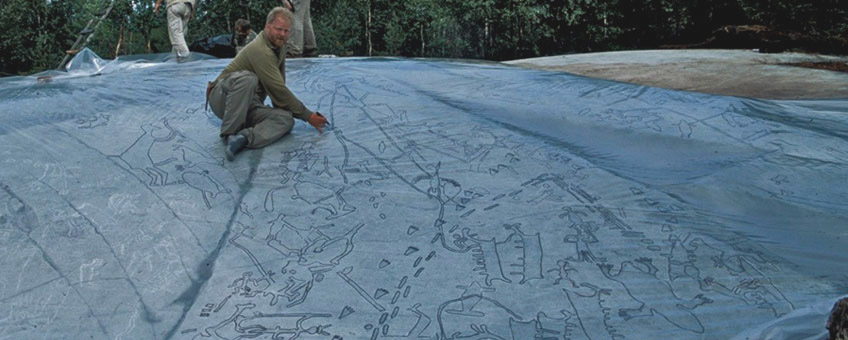

In addition to the obvious interest of the site itself, though, the ensuing method of documentation is pretty awesome: Jan Magne Gjerde and his team camped out for ten days and traced all of the petroglyphs with chalk, covered the whole thing with huge plastic sheets, and then traced onto the sheets with felt-tip pen the graphic storyboards seen on the rocks below. This could then “be brought back home and properly photographed and documented.”  [Image: The petroglyphs and their tracing paper; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

[Image: The petroglyphs and their tracing paper; photo courtesy of Jan Magne Gjerde, via Past Horizons Archaeology].

It should be published as a graphic novel! The world’s oldest comic book.

Meanwhile, as part of the ongoing Venue project—which has slowly been accumulating posts, for those of you who haven’t checked in for a while—we have been visiting a number of petroglyph sites out west in the United States, including images of animal hunts and atlatl-throwing etched into the rocks outside Las Vegas, of all places, and Utah’s famous “Newspaper Rock,” a kind of literary pilgrimage site, or monument to narrative media.

But these sorts of sites also always make me think that we cannot be far away from having easily deployable, personally affordable, field-rugged 3D milling machines capable of carving petroglyphs of our own into hard rocks anywhere in the world. Set up a Petroglyph National Sacrifice Zone or a Petroglyph Park on private rocky land somewhere in the Peak District or the mountains northeast of Yuma and build up the scaffolding for your inscription robot -slash- writing machine, and a future mythology of rock glyphs might emerge, carved two inches deep in solid granite.

[Image: Field scaffolding set up to study rock art in Egypt; photo ©RMAH, Brussels, courtesy of YaleNews].

[Image: Field scaffolding set up to study rock art in Egypt; photo ©RMAH, Brussels, courtesy of YaleNews].

Literature becomes a place you visit, a rock-carving district of canyons and massifs tattooed with bands and sprays of plots and character arcs. Shelled, self-repairing robots chisel all day and night, GPS-stabilized and surrounded by clouds of rock dust. Goggled supervisors—librarians of geology partially deafened by chisels—wander the site, preparing themselves to someday lead tours through this labyrinth of glyphs and words.