[Image: Stalag Luft III from The Great Escape; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: Stalag Luft III from The Great Escape; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

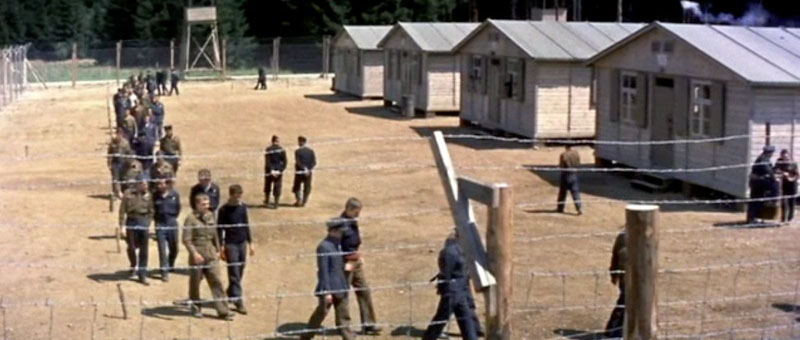

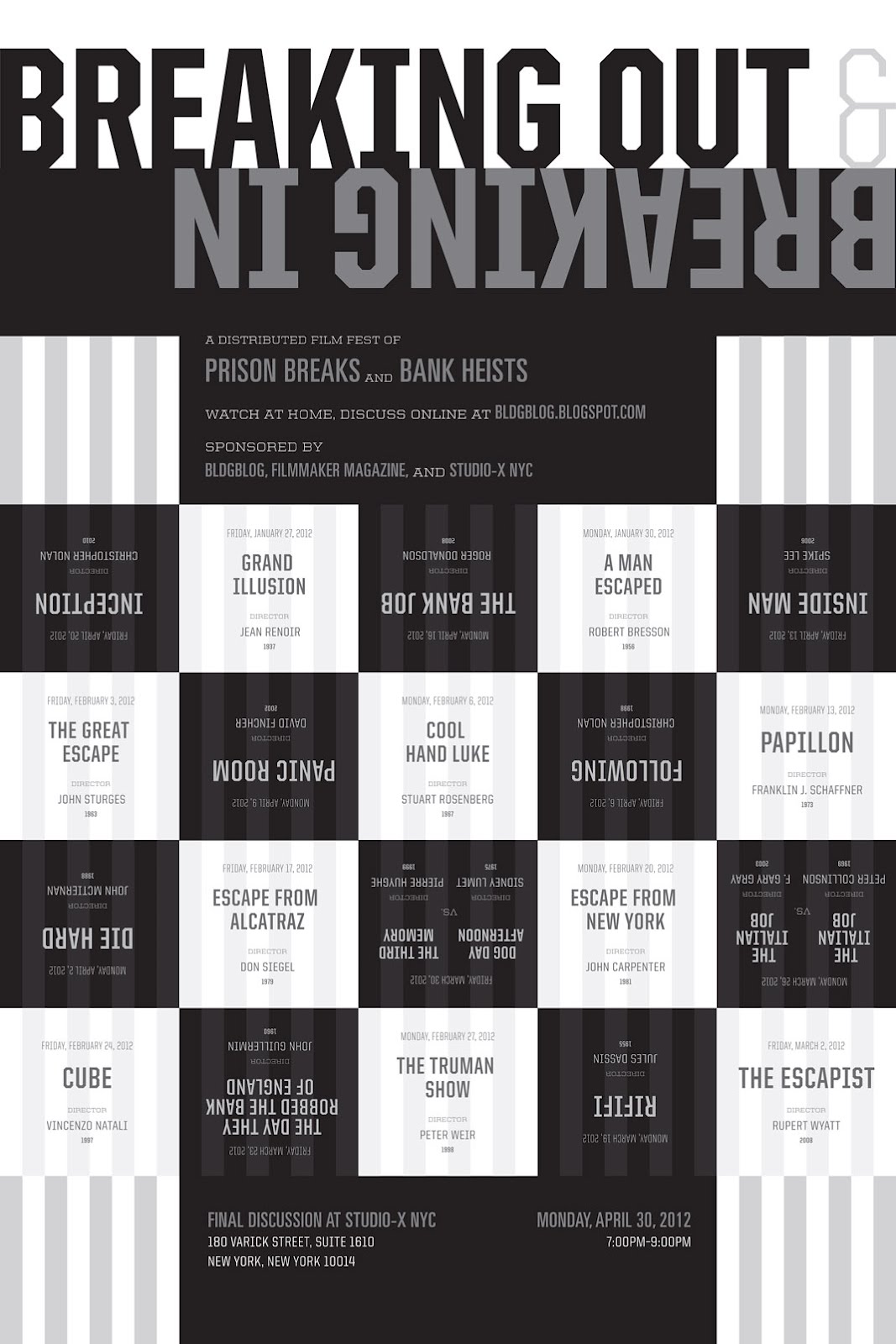

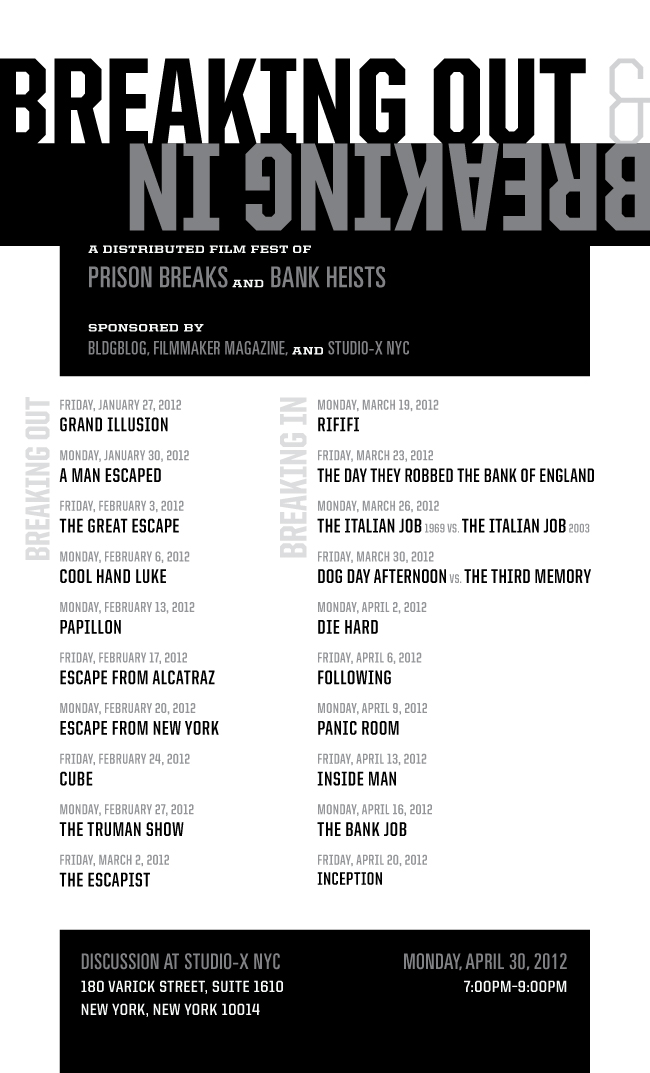

Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists—co-sponsored by BLDGBLOG, Filmmaker Magazine, and Studio-X NYC—continued recently with The Great Escape (1963), directed by John Sturges.

For those of you new to the fest, from January to April 2012 we will be watching a curated series of films at home, then discussing those films online; here is the complete schedule.

[Image: A guard tower from The Great Escape; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: A guard tower from The Great Escape; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

As usual, I’ll be focusing on the spatial premise of the film, not its directing, characterization, or dialogue; the idea is not to experiment in film criticism but to explore various scenarios of escape.

Also, as usual: there are spoilers ahead!

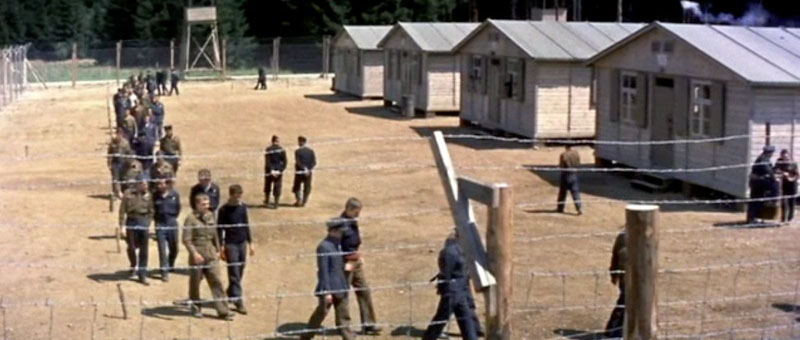

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

The film opens with the arrival of several truckloads of Allied war prisoners at a well-fortified German camp in the forests of western Poland. The lighthearted and substantially less than serious tone of the film is immediately made clear, however, not only through the jaunty title score but in the actions of the prisoners themselves as they spill out into their new environment.

Right away, escape is on their minds; we see them kneeling down to look for weaknesses beneath the boarding houses, scanning the barbed perimeter fence, and discussing the logistics of tunneling out into the woods beyond. In fact, several half-baked attempts at escape are made in the first few minutes of the film.

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

The prisoners disguise themselves as rural day workers, for instance, hoping to sneak out through the front gate, yard tools in hand—but they are spotted right away and sent back. Then several men camouflage themselves beneath forest debris, riding out on trucks under piles of pine branches—before the stabs of a menacing pitchfork convince them to pop out from this botanical ruse and surrender.

[Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

In short order, we learn that the camp was specifically built for these men. Flipping through the files of his newly arrived prisoners, and speaking with obvious exasperation as he reads their dossiers of escape—”escaped, recaptured, escaped, recaptured,” Luftwaffe Colonel von Luger sighs, throwing files across his desk—the superintendent explains that the camp is, in fact, inescapable.

“There will be no escapes from this camp,” he says flatly—to which the British Captain Ramsey replies that “it is the sworn duty of all officers to try to escape. If they can’t, it is their sworn duty to cause the enemy to use an inordinate number of troops to guard them, and their sworn duty to harass the enemy to the best of their ability.”

Escape is part of the soldiers’ contract; it is something they are literally required to try to do.

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

But “it must stop,” the Nazi insists—however, “it is because we expect the opposite that we have brought you here. This is a new camp. It has been built to hold you and your men. It is organized to incorporate all we have learned of security measures. And, in me, you will not be dealing with the common jailer.”

Here, it’s worth recalling that the film is based on a true story, and that the actual camp—called Stalag Luft III—was located for very specific topographical reasons, as if applying the concept of terroir to prison construction. More specifically, the sandy soil upon which the camp was built was seen as all but impossible to tunnel through.

Last month, on his fantastic blog Through the Sandglass, geologist Michael Welland discussed the film’s geology of escape: “The prisoner of war camp was built, intentionally, on the sandy soils of the forests of today’s western Poland, along the banks of the Bóbr river. Intentionally, because the river valley is filled with sandy sediments deposited from melt waters of the Ice Age glaciers and carried by the ancestral Bóbr. And sand is difficult to tunnel through. Very difficult.” Additionally—and much more visibly—”the excavated sand from the tunnels was immediately visible if deposited against the darker topsoil” outside, which leads to one of the escapees’ more interesting innovations.

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

One of the British POWs fabricates a kind of illicit earth-moving garment meant to be worn inside the prisoners’ trousers; filled with dark soil from the tunnels soon underway beneath the boarding houses, these string-operated bags can be dumped surreptitiously into the gardens outside. This is reminiscent, of course, of the garden scene in Grand Illusion, which we watched last month, but it also allows for the oddly comic sight of prisoner after prisoner walking out into the garden, only to evacuate this terrestrial excess down their pant legs, literally soiling the sandy ground.

But this is not the only method the prisoners use for getting rid of surplus soil. In a surreal scene inside the camp’s erstwhile cafeteria and study hall, exaggerated shudders begin to pass through the roof of the building, lurching and convulsing as if in an earthquake—which, in a sense, is exactly what’s happening, as we learn that the diggers have begun storing their dirt above the rafters in the attic of the hall. Alas, the unbelievable rolling seismicity of this scene is the last we see or hear of this comically artificial tectonic activity.

[Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

Which brings us to the buildings.

As in A Man Escaped, we see that, by dismantling the everyday environment in which we are trapped, we might reveal hidden tools of escape—and then to assemble ways out. In this case, the boarding houses are taken apart from within, their wooden planks strategically removed so as not to induce structural collapse (save for one scene involving an over-enthusiastic campmate collapsing through his newly weakened bed frame).

In the architectural equivalent of cutting hair with thinning scissors, the buildings are lightened of their wood, which is then taken below ground and assembled into bracing for the tunnels.

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile Matta-Clark of the camp; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile Matta-Clark of the camp; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

As all this unfolds, the tunnels expand below.

In a well-composed shot, we see Charles Bronson—who has been unspooling string from one end of the tunnel to the other—join two fellow diggers to form a kind of string trigonometry at the tunnel head. Using a plumb bob and pencil, they—incorrectly, as we learn later—determine the tunnel’s length.

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

But it’s all for naught. The tunnel (one of three simultaneous excavations) is soon discovered. One of the Nazi guards inadvertently reveals it when he spills tea onto the floor of a boarding house kitchen; the water rapidly drains down through the tiles without trace, indicating some sort of void below. And into the void go the Nazis.

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

In any case, I could recount the events of the film ad nauseam, as its procedural tracking of the tunneling process—which, luckily for the prisoners, included two other escape routes from which to choose next—lends itself well to description. But I’ll instead just make a few final points, and then recommend that you check out the movie yourselves:

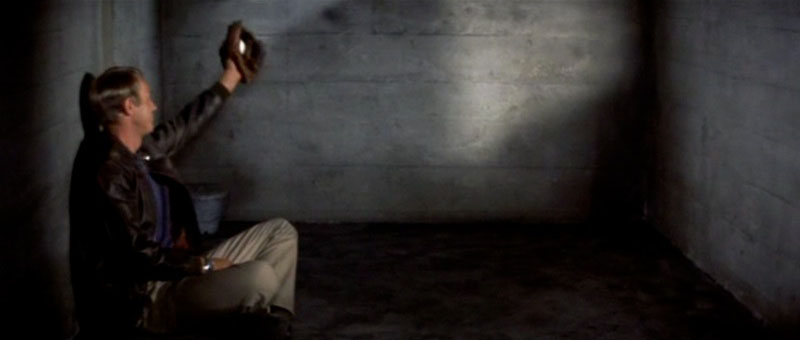

At one point early in the film, Steve McQueen’s baseball-tossing character, Captain Virgil Hilts, proposes an absolutely idiotic method of escape, in which he and a fellow inmate will literally burrow through the earth “like moles,” passing the dirt behind them, one at a time, as if swimming breaststroke through the solid matter of the planet. After detailing his ridiculous idea, McQueen self-confidently juts his head forward, making a kind of monkey face, as his future collaborator tries not to laugh beside him.

[Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

Unsurprisingly, however, the plan doesn’t work.

[Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

Captain Hilts and his Scottish sidekick are almost immediately recaptured and sent to “the cooler,” a building filled with unfurnished concrete cells (perhaps foreshadowing McQueen’s role in Papillon a decade later).

But fear not! Oh, ye McQueenites. Captain Hilts later finds his odd terrestrial fantasy indirectly fulfilled when he has an opportunity to pop his head up out of a hole in the earth—like a mole!—and look back at the camp from which he is about to escape. He is beyond the camp’s perimeter, though there is still a long way to go.

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

Later, with freedom nearly within his grasp and his fellow inmates scattered throughout the Polish and German countrysides, McQueen tries to jump a stolen Nazi motorcycle over a barbed-wire border into Switzerland.

[Image: Border games; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Image: Border games; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

But that, too, does not work, and McQueen is thrown back into the cooler.

The rest of the film is peppered with counterfeit documents and rewoven clothes, secret desks inside tabletops and cupboards full of smuggled foods, homemade potato whiskey and, all along, the spaces of the tunnels themselves, three simultaneous acts of excavation that, in their real-life versions, were a “legendary feat of engineering,” according to the New York Times.

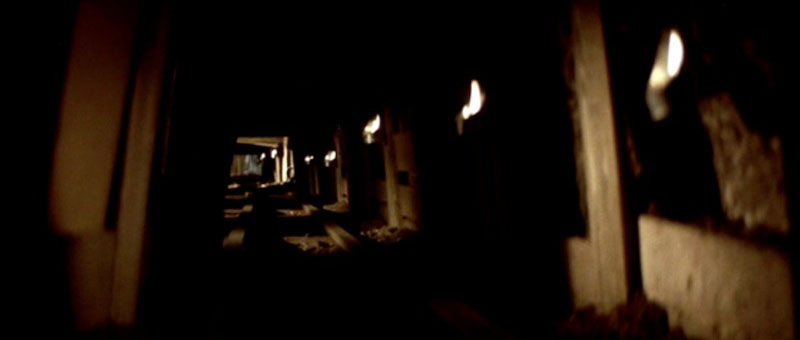

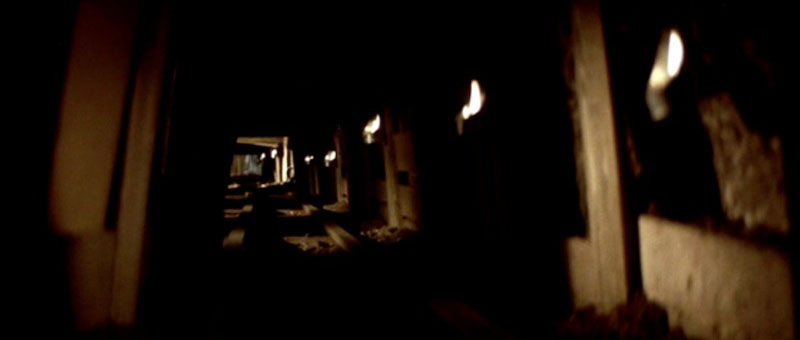

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of Metro Goldwyn Mayer].

As that article goes on to explain, a team of “British-based engineers, battlefield archaeologists and historians” recently tried to repeat the feat of digging these tunnels, producing a “replica tunnel” to test their theories of how the originals were created:

The team’s task was to employ “reverse engineering” by uncovering the tunnels and what remained of the tunnelers’ jury-rigged equipment to replicate the wartime fliers’ ingenuity. Ultimately, the team members were stunned that, even without the menace of the ever-watchful Nazi camp guards, they were unable to match their wartime counterparts fully, particularly in the most crucial skill, digging a tunnel 30 feet below the camp surface without repeated collapses of the sandy soil above.

The archaeological side of this 2011 investigation revealed the extent of the “improvisational engineering” we mentioned earlier, whereby everyday spaces and objects are dismantled and reassembled into tools of escape. For instance, the archaeologists uncovered “a set of rusting trolley wheels, the metal scavenged from remnants of a campsite stove and a coil spring taken from prison gramophones; wood paneling for the tunnel’s roof and sidewalls, fashioned from the prisoners’ bed boards; and a ventilation pump with a bellows and piping made from a prisoner’s kitbag, ice hockey sticks and tins of powdered milk. The pièce de résistance was a rusting radio made from a biscuit box, the wiring stolen from the prisoners’ huts and batteries scrounged from German guards.”

For more, check out the film itself.

(Thanks to Peter Smith for pointing out the New York Times article when it first came out! Up next: Escape from Alcatraz on Friday, February 17; posts about Cool Hand Luke and Papillon are forthcoming soon).

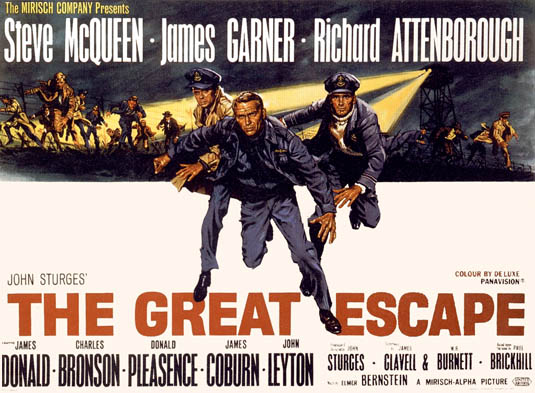

[Image: The Great Escape from MGM].

[Image: The Great Escape from MGM]. [Image: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Image: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Images: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Images: From The Great Escape, courtesy of MGM].

[Image: Stalag Luft III from

[Image: Stalag Luft III from  [Image: A guard tower from

[Image: A guard tower from

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of

[Images: Establishing the camp; courtesy of

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of

[Images: Looking for weaknesses; courtesy of  [Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of

[Image: Humans disguised as trees; courtesy of

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of

[Images: Reading the files of failed escapes; courtesy of

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of

[Images: The relaxing technique of soiling a garden down your pant legs; courtesy of  [Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of

[Image: James Garner looks up with alarm as artificial earthquake waves shudder through the roof; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile

[Images: Steve McQueen as erstwhile

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of

[Images: Measuring the tunnel; courtesy of

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of

[Images: Discovering the tunnel with tea; courtesy of  [Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of

[Image: Steve McQueen wants to burrow through the earth like a mole; courtesy of  [Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of

[Image: Steve McQueen’s mole fantasy remains tragically unfulfilled; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of

[Images: Steve McQueen as topography: the actor’s head emerges from the surface of the earth; courtesy of  [Image: Border games; courtesy of

[Image: Border games; courtesy of

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of

[Images: One of the tunnels; courtesy of

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: A view of the exhibition at

[Image: A view of the exhibition at

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: The manifesto from

[Image: The manifesto from

[Images: Excerpts from David Knight’s “growing database of arcane, marginalized, or forgotten planning practices,” part of

[Images: Excerpts from David Knight’s “growing database of arcane, marginalized, or forgotten planning practices,” part of

[Image: A printer known as the

[Image: A printer known as the  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Posters for

[Image: Posters for

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: Breaking Out and Breaking In poster by

[Image: Breaking Out and Breaking In poster by  [Image: Breaking Out and Breaking In poster by

[Image: Breaking Out and Breaking In poster by

[Image: The expansion of Manhattan island, via

[Image: The expansion of Manhattan island, via