It’s not difficult to imagine finding unexpected affinities between a specific animal species and certain types of architectural ornament, whether it’s pigeons nesting on the tops of ruined columns in Rome, bats colonizing the attic windows of single-family Victorian homes, or bees, moths, wasps, and other bugs breeding in the cracks of terracotta egg-and-dart.

[Image: A bird in Rome].

[Image: A bird in Rome].

However, it would be interesting to see if any of the following scenarios might be true:

1) Ornamental details from a particular phase of, say, the Baroque—or the Gothic, or Dravidian temple design—are found to attract a specific species of bird, whose size, nesting needs, etc., correspond exactly to the proportional details of this decorative style. Because of the foods those birds eat, however, and, thus, what seeds they later spread around their flight paths, their guano results in a very specific kind of forest growing around each building (or its ruins). The buildings catalyze their own ecological context, in other words, ringed by forests they indirectly helped create.

2) A particular type of early modern warehouse or other such industrial structure is found to house a specific species of bird, perhaps because only its frame can fit through gaps in the brickwork, precluding colonization by other species. Thus, while all other bird species in the local ecosystem have gone extinct—due to habitat loss, food-web collapse, or whatever—these birds, regally ensconced inside their protective warehouses, manage to survive. They are thus saved by 19th-century architecture—perhaps even by one architecture office’s work. A species that only lives inside buildings by Anthony George Lyster.

3) When the type of stone used to build a region’s churches erodes, weathering away to nothing, its remnant minerals fertilize a specific type of weed or small flowering plant, one that would otherwise eventually have died off. Thus, whenever you see a particular flower, you can deduce from its presence that a church built during this particular phase of architectural history once stood there. The flowers are archaeological indicators, we might say: botanical traces of architectural history.

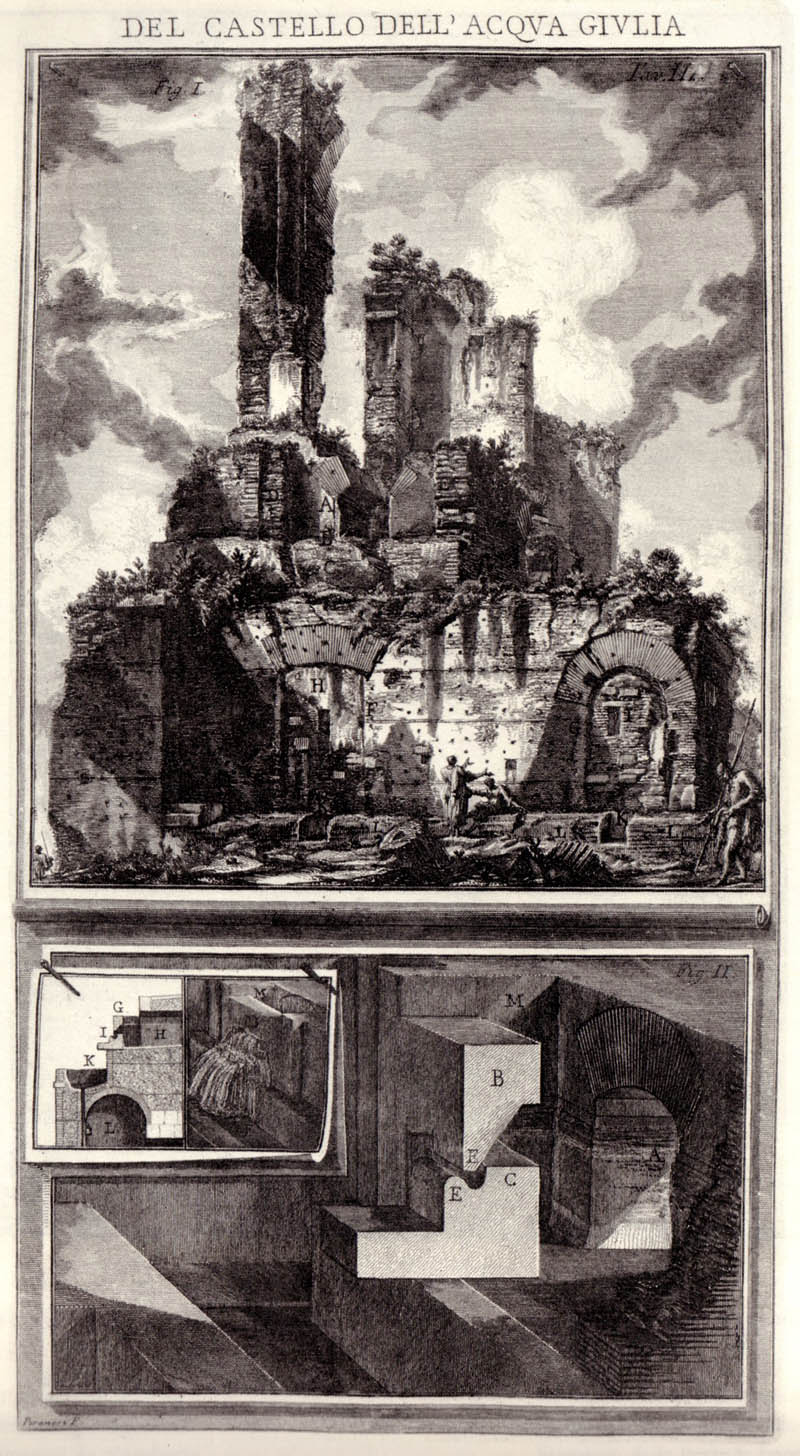

[Image: Del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia by Piranesi].

[Image: Del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia by Piranesi].

In all three cases, these buildings’ unanticipated side-effects would ripple outward to influence the evolutionary development of other, future species, whose ecological origins are thus at least partially predicated on the existence of a specific phase of, for example, Baroque architecture or 19th-century warehouse design. So when those architects were designing their buildings, they were also indirectly designing future species.

I doubt it's influenced any evolution or anything, but my apartment building's parking floors are built from ornamental bricks like the ones in the image linked below; almost every single center hole is now occupied by a little finches' nest, since they're too high up for rodents, and all the other birds around are too big.

http://images.cdn.fotopedia.com/154r509v8jcbi-_dYRzgYirGg-image.jpg

I suspect some of what you hypothesize here could be true. But what's cool is that it's testable! Just need to find some funding and the right researcher/student 🙂

Very interesting — did anything in particular prompt this line of speculation?

Visiting Valletta (Malta), a fortification city build up entirely of limestone, it stroke me that the thread has changes over time. From 1500 century earth level intrusion to WWII bombardments it has lost almost all protective nature.

The biggest thread to limestone fortifications in our time seems to be bio deterioration caused by pollutants, salt, algae and fungi and these micro scale processes care mostly about stone properties and climate and less about wether its baroque or warehouse architecture.

I have been wondering if it makes sense to talk about "wall ecologies" to frame a discussion like the one you put up here. I think it has to include several scales if it has to make sense, i.e. I am not sure if the Neufert-approach can give the full answer.

Reading Subnature by D. Gissen makes me think that 'dankness', 'matter', 'dust' and 'puddles' could be the breeding ground for species to nest. Would there be any kind of prevailing angle, basin, ornament, plantings that comes along with any specific type of architecture that we could look for? It could be about pattern recognition and combinations. Lets say olive trees and the caryatids in Roman Villa makes a perfect environment for a specific insect that has been in coevolution with a specific beetle that can actually dwell in the curls of her hair.

Oxford Rock Break Down Laboratory

http://www.geog.ox.ac.uk/research/landscape/rubble/#intro

Yea, the sparrow hath found an house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, [even] thine altars, O LORD of hosts, my King, and my God. Psalm 84

I remember reading about how Herzog & De Meuron's winery in the Napa Valley had unintentionally created the optimal housing for local snakes in the walls of the building. I can't remember reading whether or not this was perceived as a bad thing. I imagine the snakes would do well to kill off all rodents in the winery.

Hi Geoff…

I know a couple of things that touch on this.

1) There are places on British castle ruin walls where specific species of lichen or moss (I forget which now) have taken hold because they prefer more acidic conditions and hundreds of years ago these particular spots on the walls were where the latrines were.

2) There are documented cases of plants gaining a foothold in new areas around small boulders because birds like to sit on the rocks and while they are there they defecate and pass on seeds that they ate elsewhere. Subsequent rain washes the seeds down to the base of the rock where in takes root.

3) Richard Dawkins' great book "The Extended Phenotype" has some great stuff about species altering the environment around them, facts that could be projected out into the man-made environment.

4) And of course piers and docks are just totally great environments for many species of barnacle and mussel.

Brian, I would love to test these ideas somehow, especially the forest one. It would be incredibly exciting, I think, to see that, say, church bell towers built during a specific phase of architectural history came to house a species of, for instance, sparrows—to keep the sparrow theme going—which, in turn, led to the proliferation of thickets or forest cover due to seeds being spread specifically by those sparrows.

In other words, the bell towers—architectural objects—become radiation points, or facilitators, for future landscapes.

Remove the bell towers, and you remove the sparrows, and you remove the conditions by which the forests were maintained. In the absence of the bell towers, the landscape around it begins to change.

Stephen, nothing in particular—I was just looking at birds congregating on top of a ruin and this is what I started thinking about.

Anders, "wall ecologies" would be an awesome thing to explore further! Maybe even consider submitting a short paper about that idea—or a series of hypothetical cross-sections—to the Animal Architecture call-for-ideas. You have about three weeks to put something together.

Chris, have you read the admittedly probably very over-simplified narrative of island formation? In a nutshell: undersea volcanic activity heats the water, killing fish; birds from nearby islands or the mainland fly out to feed on those fish; soon, new rock forms break the waterline, forming dry land; the birds start crapping onto those rock surfaces, delivering seeds and rudimentary soils/fertilizers; the landmass continues to grow due to the undersea volcanic activity mentioned above; the seeds begin to sprout.

Soon you have an island covered in meadows and forests, and it can all be traced back to dead fish and bird crap (again, I sense this is horribly over-simplified).

Anyway, the idea here is to analyze a particular phase of architectural history, in terms similar to that volcanic island, to see if certain buildings, building types, or classes of architectural ornament have facilitated the creation of new landscape ecologies.

I'm reminded of the beehives they found while reconstructing the roof of Rosslyn Chapel. Here's the link to the "Times" article:

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/scotland/article7080735.ece#cid=OTC-RSS&attr=797084

Liminal, I love that story; here's my own spin on it from last year.

I think these scenarios are good counter-arguments against the thinking that human infrastructure development destroys the natural ecology of the area of activity. Instead human infrastructure can be thought of not as 'destroyer' but as a 'game-changer' as these structures could create an entirely new ecology as mentioned in your scenarios above.

There's always been advocates of eco-friendly buildings, green technology etc. But I say, let's build what needs to be built and then just let the natural course of life grow around it. Come to thnk of it, constructing an eco-friendly building that encourages the propagation of a certain species of sparrows is more 'artificial' than constructing a building and letting nature decide what birds it wants to house there.

"Termites show the way to the eco-cities of the future" (in the New Scientist)

=> http://www.allbusiness.com/science-technology/earth-atmospheric-science/13959379-1.html