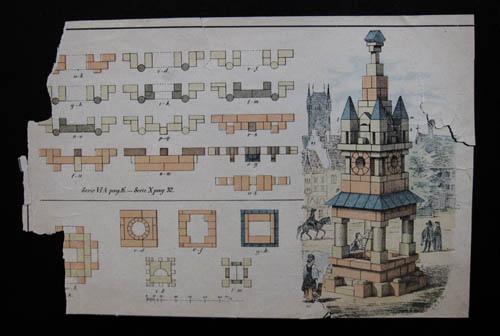

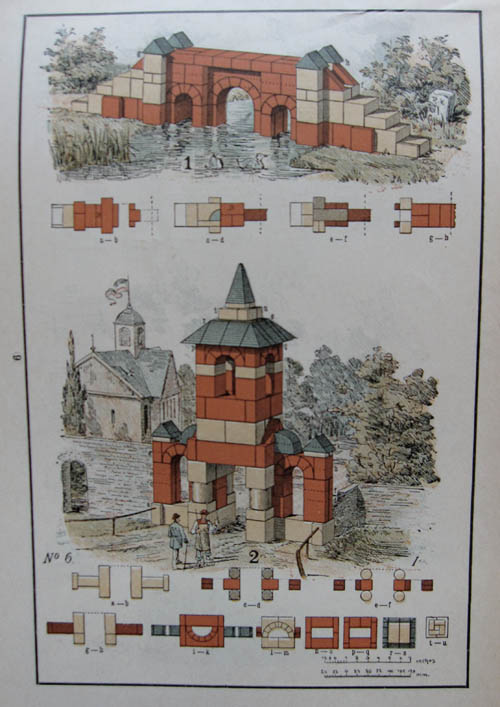

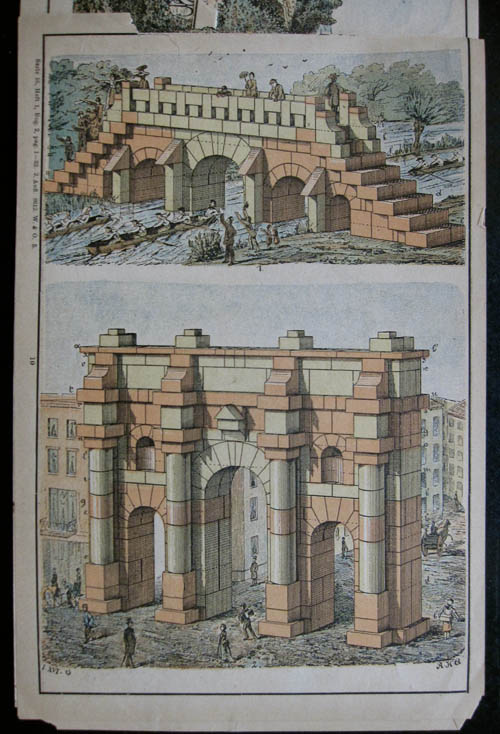

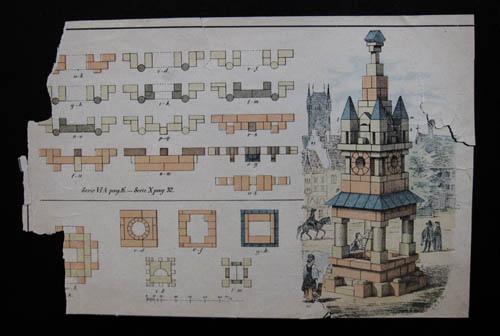

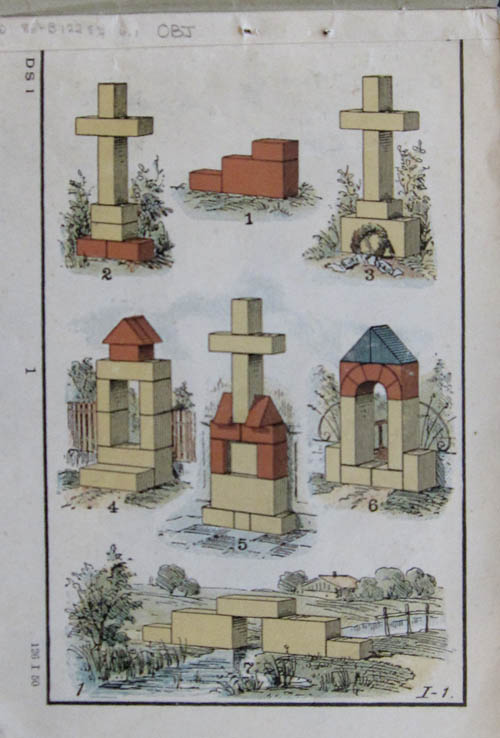

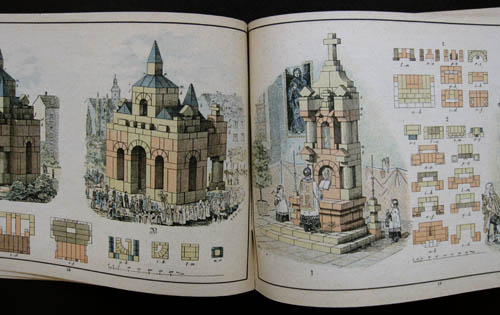

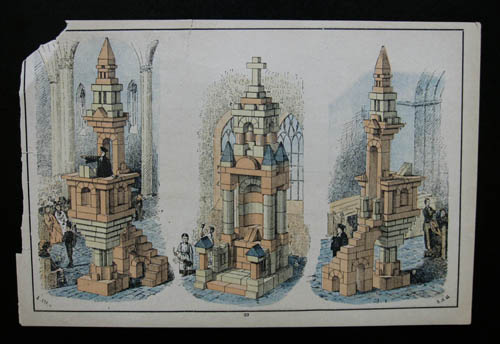

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the CCA].

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the CCA].

While down in the CCA archives last week, I had some time to explore a number of old instructional booklets for wooden children’s toys.

One such book, called The Art of Architecture of Building With Given Model Stones, explains that “It will be seen from the title of this book that it is intended to be a guide in the construction of larger buildings with the aid of model stones, indefinite in number, but of certain fixed shapes.”

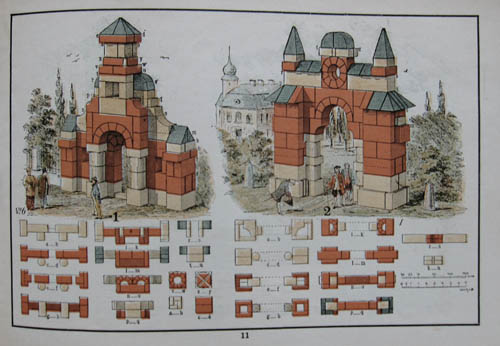

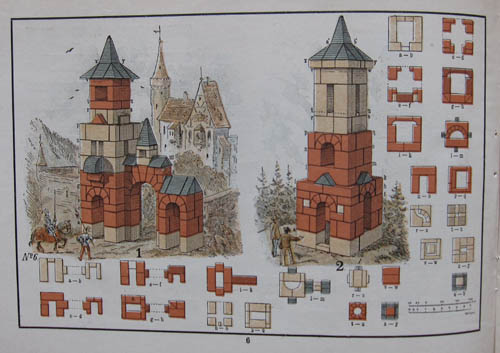

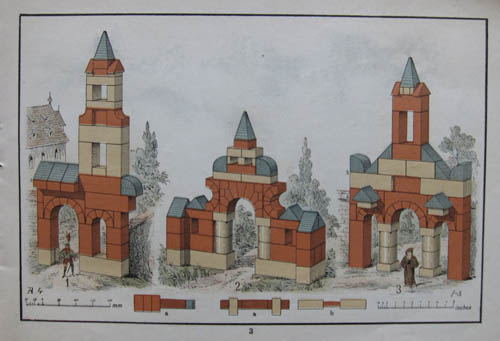

[Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the CCA].

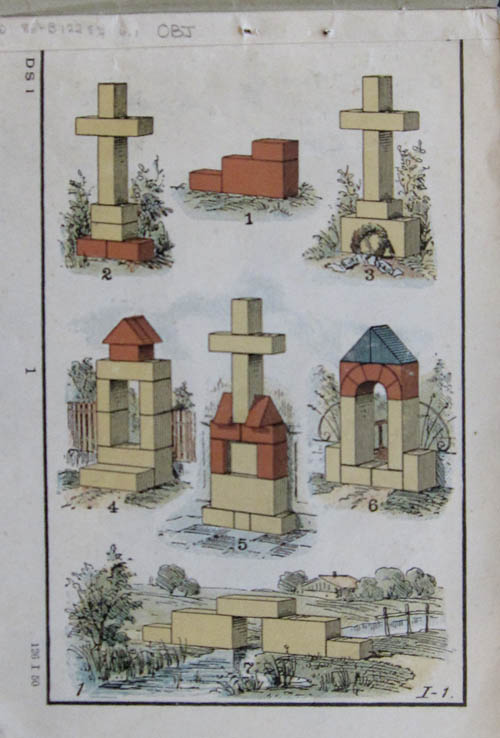

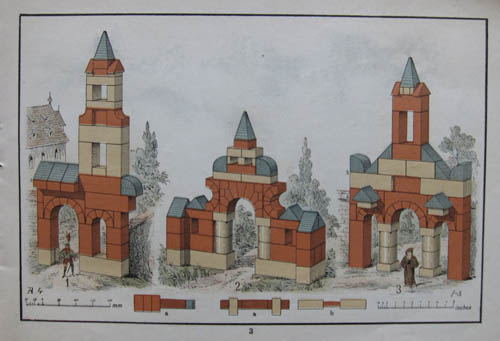

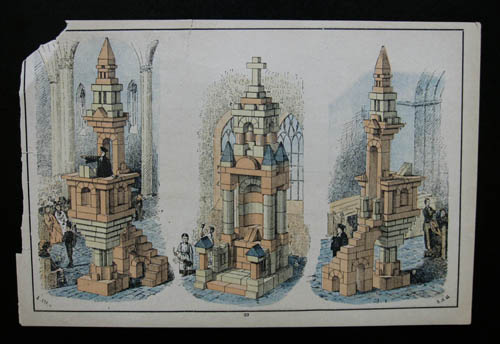

From the very basic—

[Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the CCA].

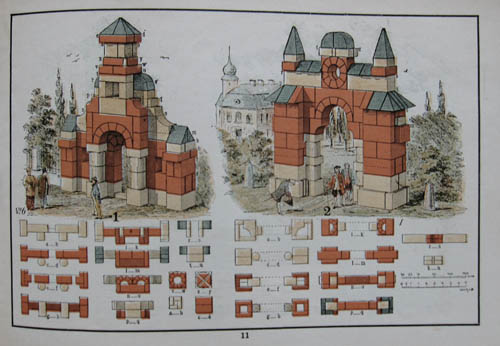

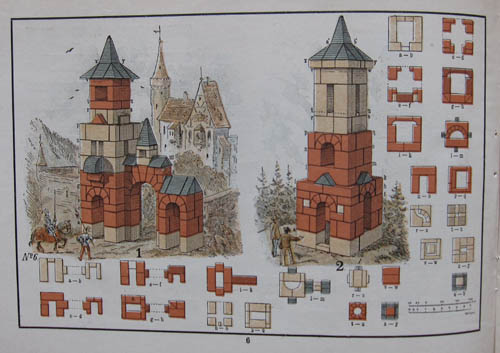

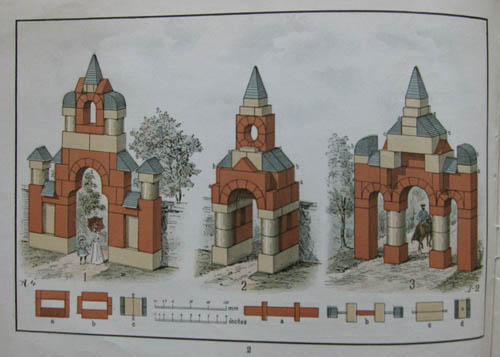

—to the much more complex—

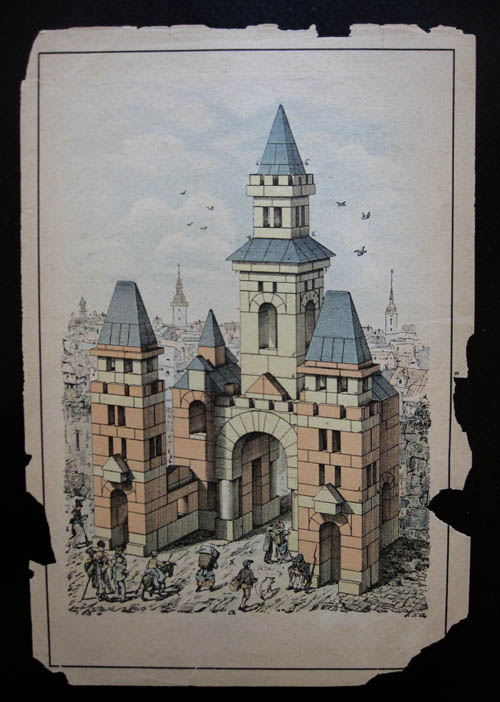

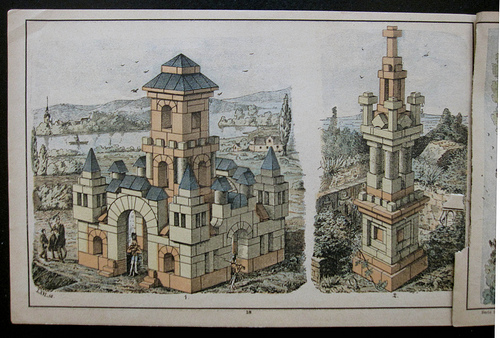

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the CCA].

—these toys were imagined as pedagogical tools for the training of the young human mind.

As such, Richter’s toys did not at all seem out of place down there in the CCA archive, stored near other such fading boxed sets as the “Object-Teaching Forms and Solids” of A.H. Andrews & Co., Chicago, dating from 1890, or even “Kinsey’s Ornamental Lock Block and Toy” set, from 1875, which unfortunately used tiny wooden swastikas—hundreds of swastikas—to teach children how they, too, can fill space with interlocking, modular parts.

[Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the CCA].

Produced in the late 1800s by a company called Richter’s—”Designed and Executed by Dr. Richter’s Art-Department,” then located at 74-80 Washington Street, New York, NY—the blocks and their instructional manuals that you see here were no mere playthings; they were marketed as intellectual stimulants, Frobelian educational props, for teaching children nothing less than how to think.

At this point I might offer a slightly long quotation from the Los Angeles-based Institute For Figuring about the origins and purpose of Frobelian education:

Most of us today experienced kindergarten as a loose assortment of playful activities—a kind of preparatory ground for school proper. But in its original incarnation kindergarten was a formalized system that drew its inspiration from the science of crystallography. During its early years in the nineteenth century, kindergarten was based around a system of abstract exercises that aimed to instill in young children an understanding of the mathematically generated logic underlying the ebb and flow of creation. This revolutionary system was developed by the German scientist Friedrich Froebel whose vision of childhood education changed the course of our culture laying the grounds for modernist art, architecture and design. Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Buckminster Fuller are all documented attendees of kindergarten. Other “form-givers” of the modern era—including Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky and Georges Braque—were educated in an environment permeated with Frobelian influence.

I might also then suggest that we seem sorely lacking today in analogue children’s toys inspired by an instructional need to teach lessons in space, relation, cause, effect, etc.

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the CCA].

In any case, Richter’s blocks worked, we’re told by the company itself, because “instruction must be united with amusement.”

Indeed, an entire philosophy of child-rearing is outlined in these toy manuals. They seem to have been written more with the purpose of explaining how the human brain processes information than for telling future consumers how to use their new toys.

They are not product manuals at all, then, but manifestos of human cognitive development.

[Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

Richter’s system, in particular, “trains [children] to habits of orderliness and tidiness, especially when they know what they must keep the boxes they already possess intact, if they wish to be able to build the designs of the next Supplement Box.”

Raised in a world of these carefully regulated Supplements, Richter-building children learn to master consumer self-control and the rudiments of cognition itself—as if undergoing training in some woodblock remake of Inception.

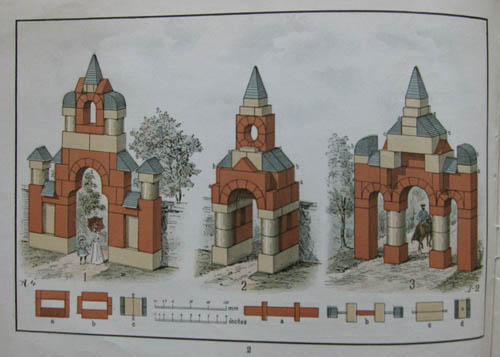

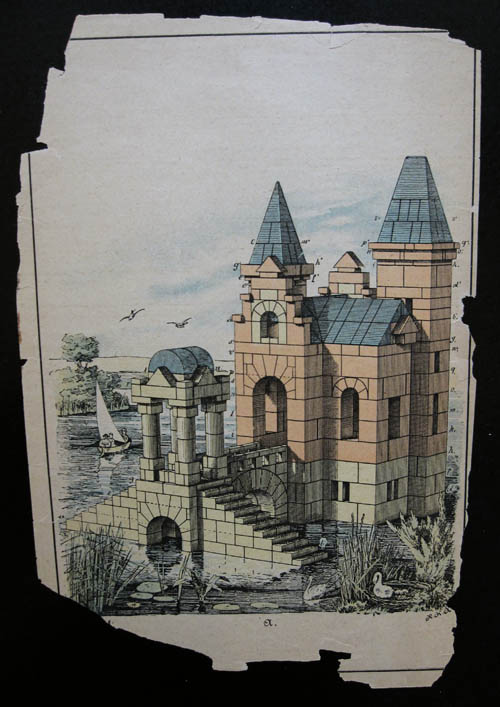

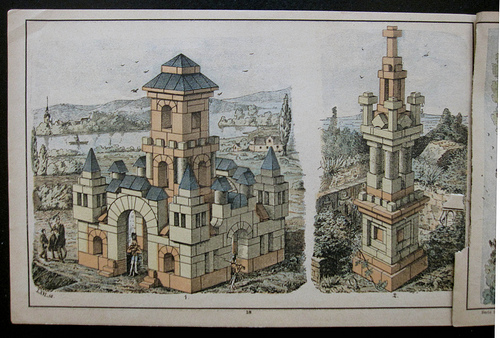

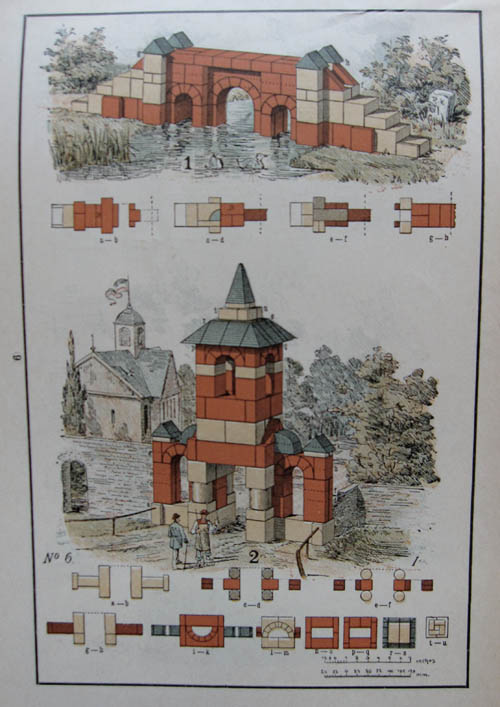

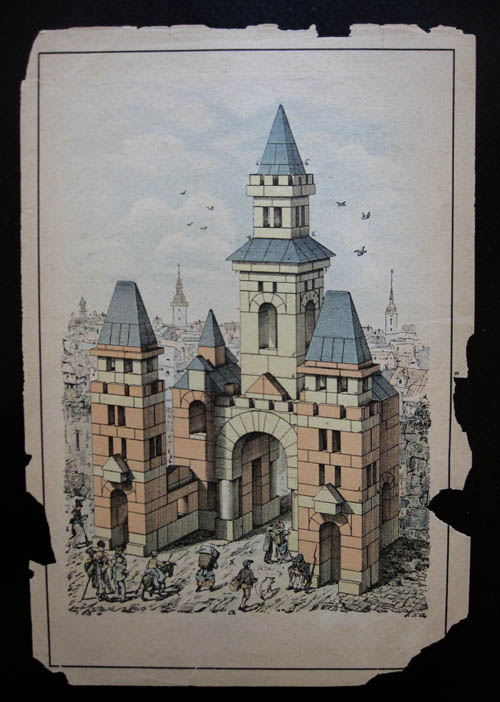

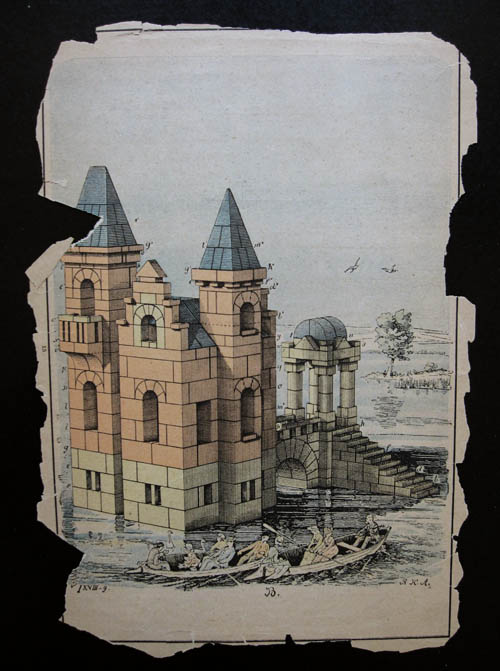

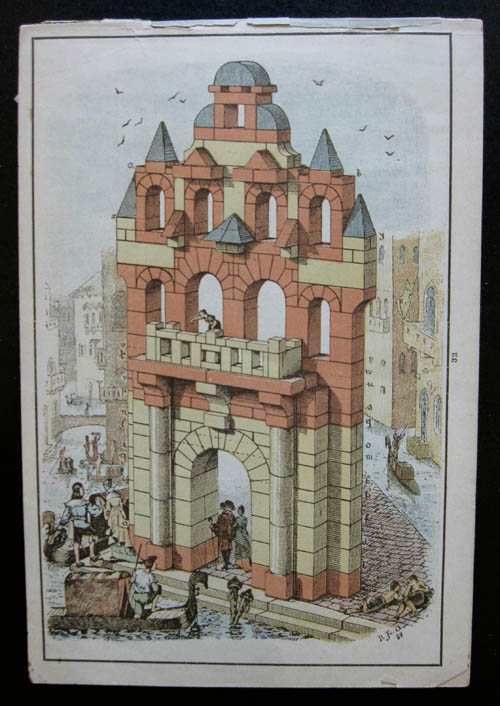

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the CCA].

There are ample warnings against straying from these directions. Not paying attention to the order of Supplements, for instance, as if your child is being initiated into a Masonic cult of basic geometric shapes, means that the child’s mind may become lost.

The children should not be permitted to construct [the designs in this book] until they have thoroughly mastered the First Stage. In this way the little architects, even the smallest of them, will be able of their own initiative successfully to overcome the various architectural problems of the present Book, and parents will soon get to recognize the importance of the Anchor Blocks as a means of inducing children to think for themselves.

However, “When once they are mastered, building becomes an unfailing source of joy as well as of instruction for children and their elders alike.”

At that point, the successful little builder “should show his parents as many well constructed buildings as possible and get them occasionally to join him in building.”

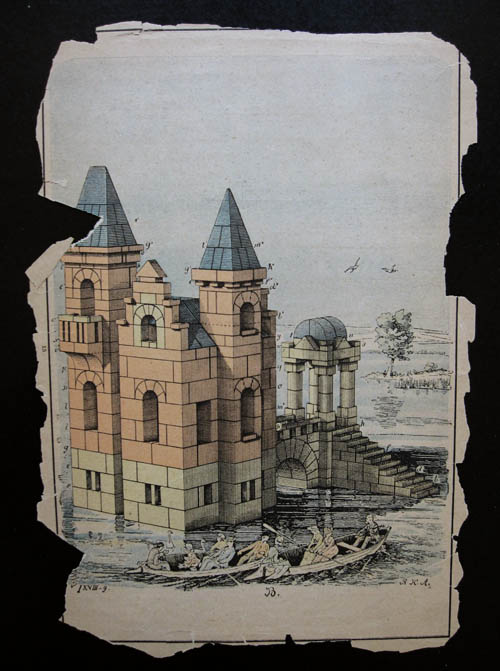

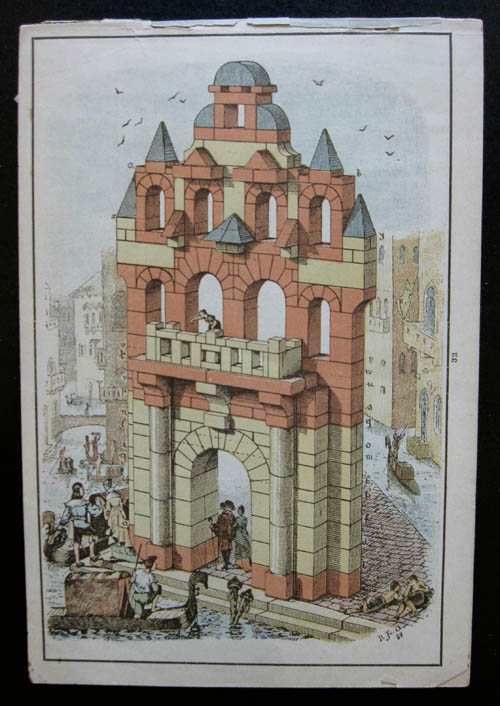

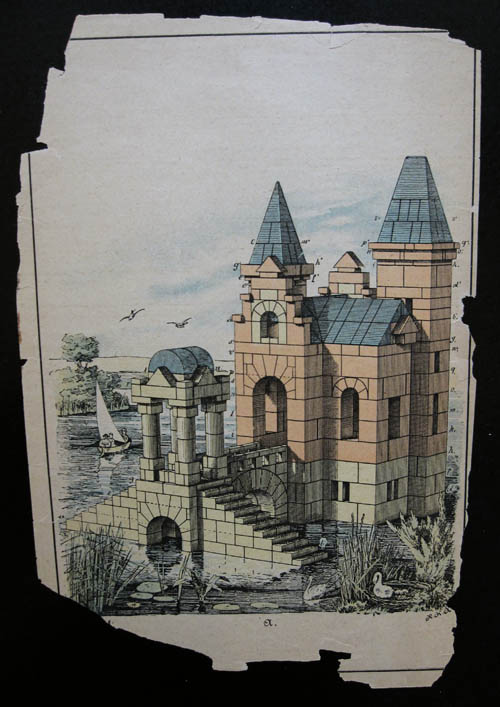

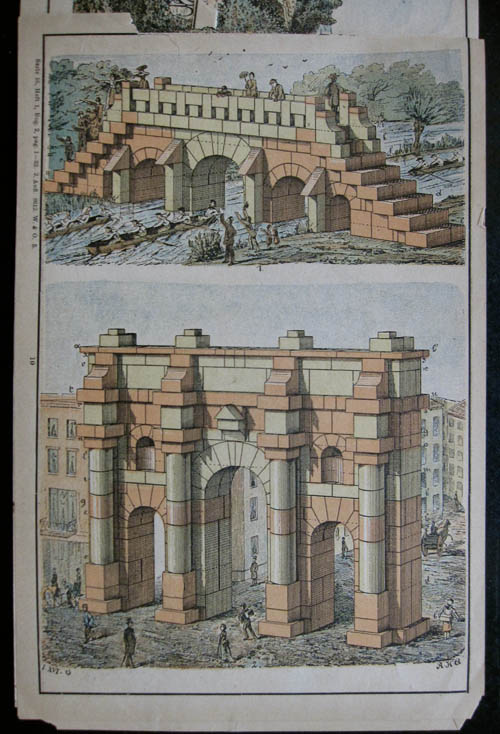

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the CCA].

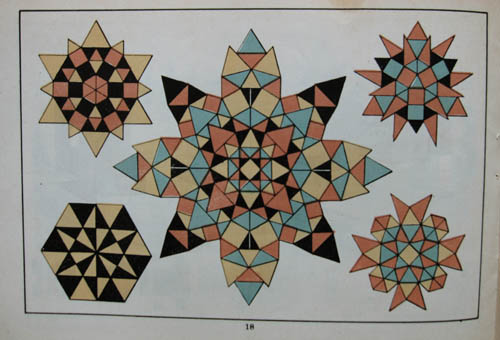

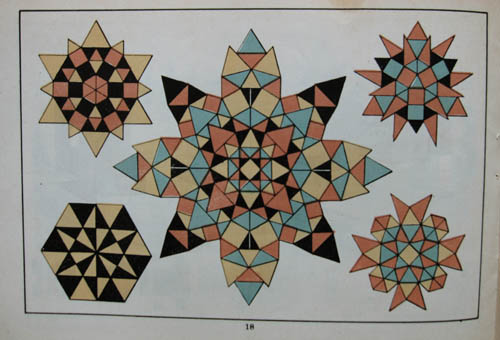

Note the gender. These toys were specifically marketed as cognitive training devices for boys. Girls were instead given flat, two-dimensional patterns, called “mosaic-games,” not at all unlike quilting templates, to play with, instead.

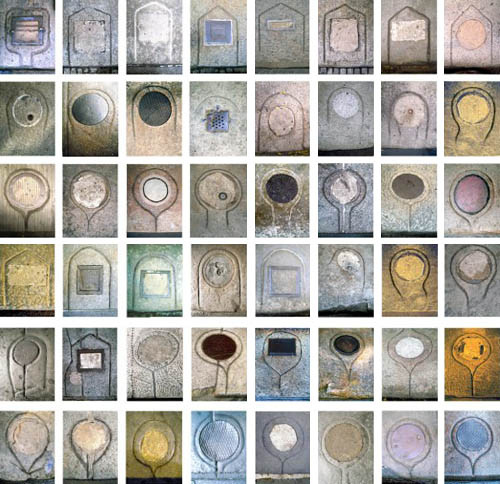

[Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the CCA].

“We have also introduced a number of most interesting marble mosaic-games specially designed for girls,” Dr. Richter’s guidebooks explain. “Contained in a handsome wooden box, [these consist] of a laying-plate and a number of specially shaped stones, which are made with the utmost precision. The patterns which can be laid with these stones are quite charming and often produce most striking and unexpected effects.”

This vision of girls reduced more or less to the status of imbeciles, tripping out on “quite charming” patterns while pushing little pieces of colored stone around on a “laying-plate,” would be a hilarious anachronism if it wasn’t also so tragic.

Men will learn to build and inhabit three-dimensional space; women can make mosaics, push rocks around, sew quilts together, and drool.

[Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

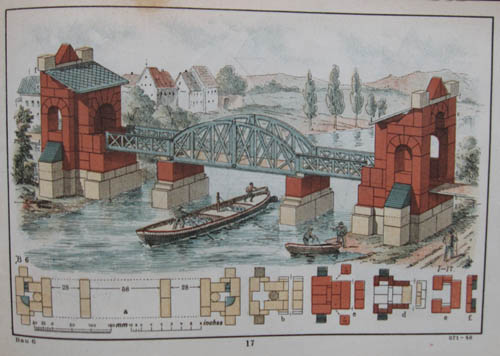

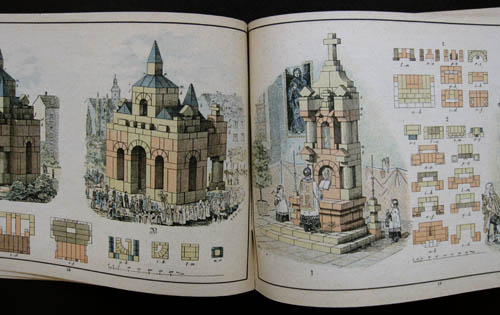

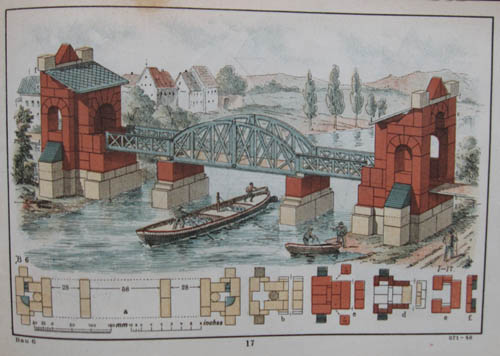

I photographed nearly one hundred pages of designs from the Richter series; I’ve included just a few here to give a sense for the overall visual language of the pavilions, churches, altars, towers, bridges, houses, walls, and more into which the woodblock pieces were meant to be assembled.

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the CCA].

However, if this sort of thing interests you beyond a single blog post, I’d recommend taking a look at the Institute For Figuring’s Inventing Kindergarten page; but I would also point you toward the CCA’s exhibition Potential Architecture: Construction Toys from the CCA Collection (1991-1992), with architecturally-themed children’s toys selected by Norman Brosterman.

A pamphlet was published to coincide with that show, and is itself worth checking out.

[Image: Courtesy of the CCA].

[Image: Courtesy of the CCA].

In describing the exhibition, the CCA wrote that Brosterman chose to focus on “twenty-one construction toys, made in the hundred years from 1850 to 1950.” These are toys, now held in the CCA’s underground archives, “that were designed to challenge a child’s creativity. The toys illustrate how children learn to invent relationships between space, structure, and building forms, and hence to better understand the world around them.”

Each one of these modular toy sets “invited children to organize its prefabricated toy buildings into entire cities”—a remark that once again brings to mind those early, all too brief training scenes seen in Inception, where Leonardo DiCaprio describes the flexible architecture of urban maze-creation to a pupil named Ariadne, who then takes to her lessons suspiciously well.

But might a dream academy of Inception-scale urban alteration be the Frobelian education to come, for a future, highly fortunate generation of children? In a kindergarten of machine-assisted sleep, they will assemble cities indefinite in number, but of certain fixed shapes, outdoing any urban form that’s come before.

#CCA

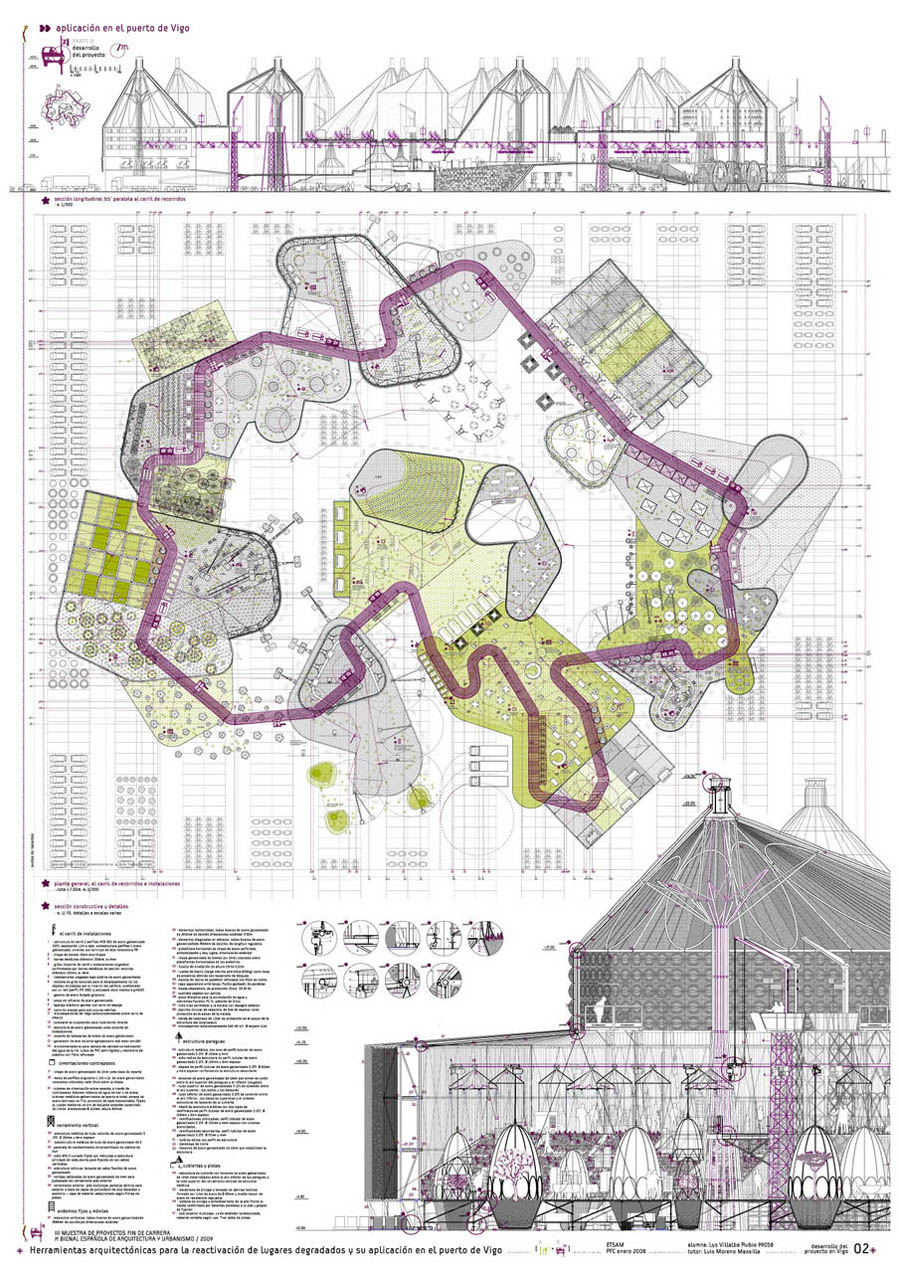

[Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio].

[Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio]. [Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio].

[Image: From a project by Lys Villalba Rubio]. [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library].

[Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library]. [Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library].

[Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library]. [Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library].

[Image: Watership Down by Maier Yagod and Jon Reed at the Cleveland Public Library].

[Image: A film still from

[Image: A film still from  [Image: A 20,000 square-foot underground shelter by

[Image: A 20,000 square-foot underground shelter by  [Image: Photo by Spencer Weiner for the

[Image: Photo by Spencer Weiner for the

[Images:

[Images:  [Images: Photos by Linda Pollak, courtesy of

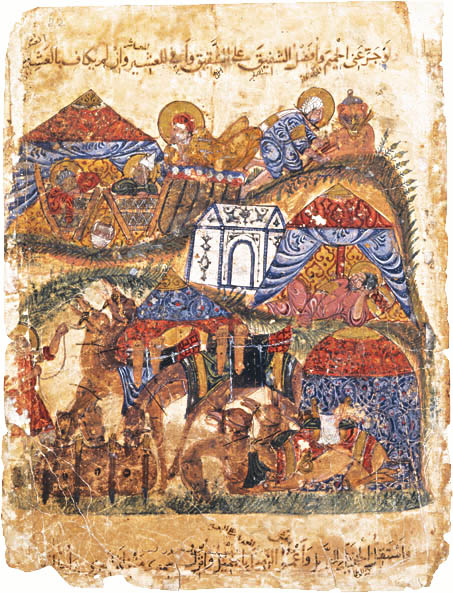

[Images: Photos by Linda Pollak, courtesy of  [Image: Institute of Oriental Studies, St. Petersburg/Giraudon/Art Resource, via Saudi Aramco World].

[Image: Institute of Oriental Studies, St. Petersburg/Giraudon/Art Resource, via Saudi Aramco World].

[Images: The

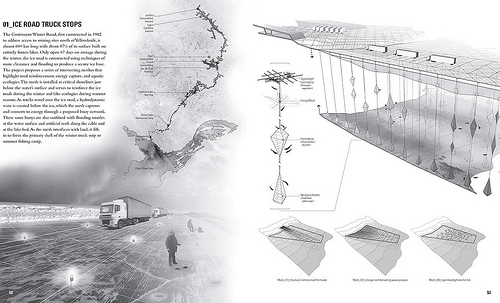

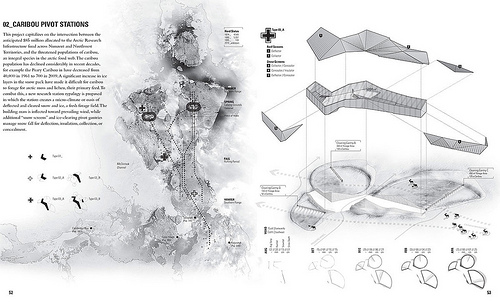

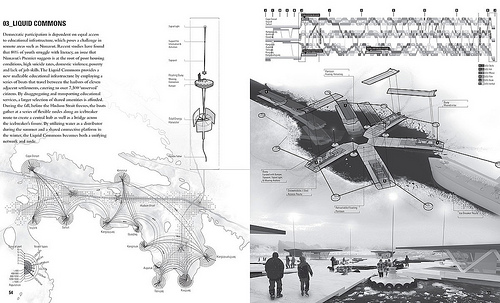

[Images: The  So far, I’ve covered graduate research presentations here at the

So far, I’ve covered graduate research presentations here at the

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the

[Image: One of many pages from the voluminous archive of Richter’s toy manuals at the  [Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the

[Image: Page from a Richter’s toy manual; courtesy of the  [Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the

[Image: An early stage in assembling Richter’s “anchor blocks”; courtesy of the

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the

[Images: Complex spatial objects from an advanced stage of the Richter’s toy system; courtesy of the  [Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the

[Images: Into the hypnotic spreads of a geometrical universe; courtesy of the

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the

[Images: Variation, adaptation, memory; courtesy of the  [Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the

[Image: Cognitive tools in the guise of toys, manufactured by Richter’s; courtesy of the

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the

[Images: The same building, rotated 90-degrees; by Richter’s. Courtesy of the

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the

[Images: Another structure, rotated 180-degrees for ease of spatial perception; courtesy of the  [Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the

[Image: A “mosaic-game” from Richter’s; courtesy of the  [Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the

[Image: Richter blocks, courtesy of the

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the

[Images: Richter blocks, courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

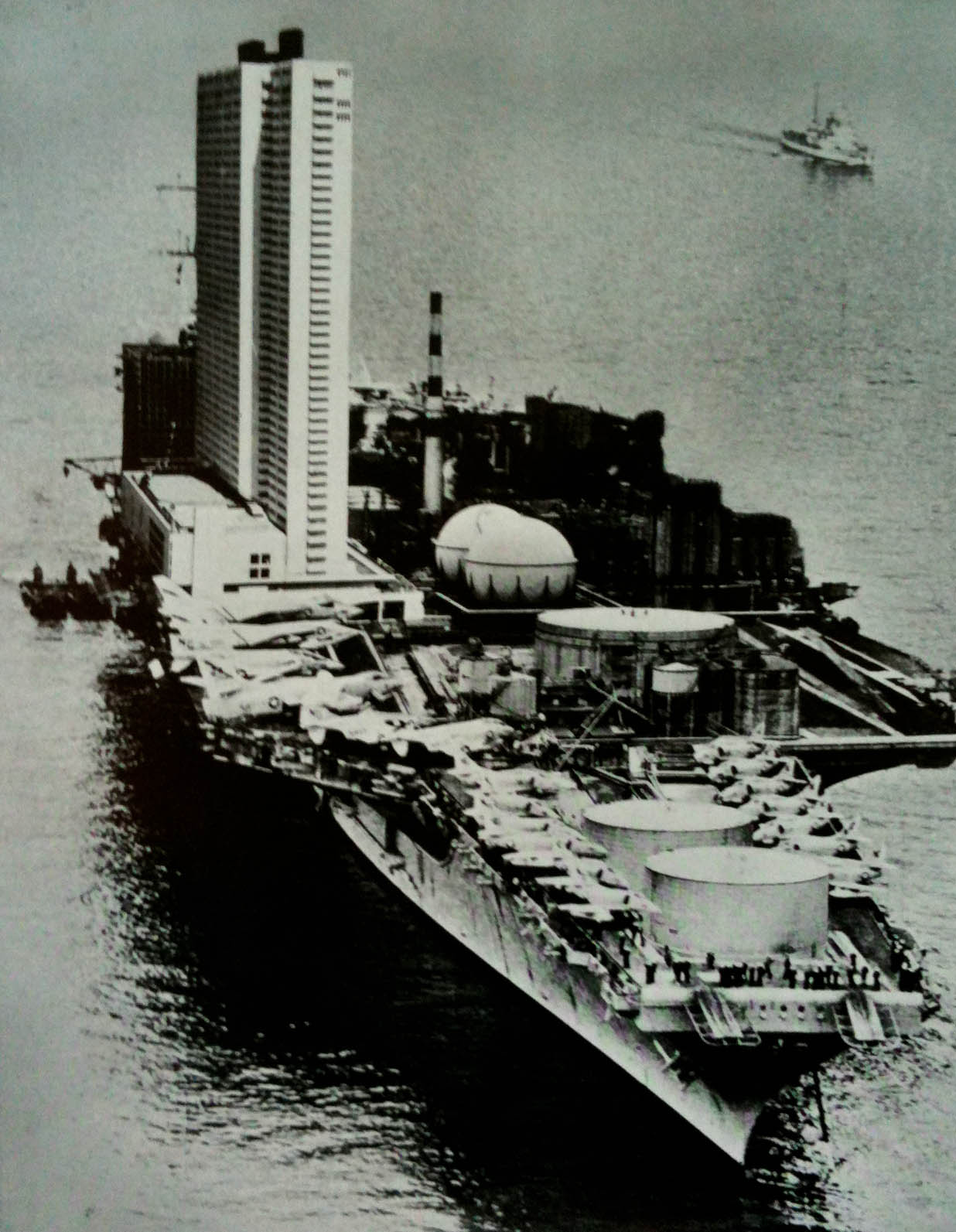

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from

[Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from  [Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from

[Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from  [Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from

[Image: By Tsunehisa Kimura, from

[Images: Ships botanically assembling themselves in the forest, from “

[Images: Ships botanically assembling themselves in the forest, from “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: The Ontario Food Terminal; image via

[Image: The Ontario Food Terminal; image via  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Photo by Emily Berl for

[Image: Photo by Emily Berl for