[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

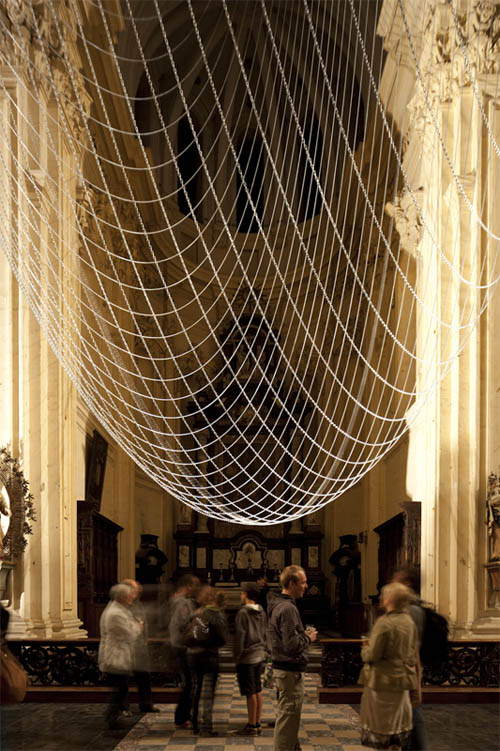

Looking at “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh, installed inside the St. Michiel Church in Leuven, Belgium, is like seeing the underlying geometric logic of Western space bleed through from a hidden dimension.

The project was at least partially inspired, the architects write, by their recognition that the church itself actually has no dome: their intervention “takes this seemingly trivial fact as a starting point and generate[s] the missing dome in a remarkable way.”

Using the design technique of the catenary, a new structure emerges in the church. The Upside Dome is a real size scale model, comprised of hundreds of meters of chain, which is literally and figuratively the counterpart of the unfinished dome.

Abstract, bulbous, heavy with itself, this network of chains thus forms an inverted counter-dome—a reflective surrogate, a back-to-front double, an upside dome—inside the nave.

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

The actual installation shots are pretty cool, as well: glimpses of the church’s innards—its otherwise unseen attics and backspaces—complete with long chains dropped down from above.

[Images: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Images: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

The final result is both model and realization, then, simultaneously a demonstration and the final product.

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

In a sense, the geometry of gravity itself collides with the ornamental excess of Baroque architecture in a surprisingly appropriate and optically interesting way: the installation suggests a kind of minimalist Baroque, where emerging nests of curved surfaces take shape, mocking and repeating the logic of the buildings around it.

[Images: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Images: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

Way back in March 2005, meanwhile, I caught a lecture by architect Mark Goulthorpe at the University of Pennsylvania, where he demonstrated a piece of software that I believe had been produced in-house at his firm; it allowed the architect to model the hanging of chains in virtual catenary curves, and thus to generate a huge variety of possible architectural shapes for future projects. He produced, with the click of a mouse, live there in the lecture hall, new species of curves in space.

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

[Image: “Upside Dome” by Gijs Van Vaerenbergh; photo by Jeroen Verrecht].

But the method of analog calculation seen in “Upside Dome“—that is, drooping pieces of chain or string through space until they stabilize—gives force and form to gravity and to the potential architecture tucked away in empty space.

The software you saw Mark Goulthorpe demonstrate was probably CADenary. It was written by Axel Killian and used in a class at MIT taught by John Ochsendorf (and others) on computational form-finding, digital-Gaudi style.

This is how Gaudi designed. Interesting to see his modelling technique become art itself.

Geoff, I love your blog and read it virtually every day, but I do have to say the lack of critical insight is a bit disappointing at times. I know you have it in you.

Really, the fact that this is a huge intrusive thing hanging in the middle of a church between the altar and the congregants either escaped your notice or isn't, you feel, worthy of commentary?! I'm not even a Christian, but that intrusion seems problematic, on the borderline of offensive really.

That, from a duo that describes their practice as having "an important focus on public space?" Pity I don't have your knack for spinning a yarn, or I'd work in a quick reference to the "Las Vegas Death Ray" mentioned in your last post.

The St. Michiel Church has vertical columns and what appear to be circular arches. Catenary arches, whether upright or hanging don't really have anything to do with that. (Gaudi's columns lean for a reason)

Those are two fundamentally different systems, two different "underlying geometric logics" and this is after all a blog about architecture, building, etc. written by someone that I know to be somewhat learned in those subjects. Maybe I'm wrong in assuming some structures courses somewhere in that learning process.

To call this thing either a model or a "calculation" is really a stretch too. It's an archithingie.

Archithingies are fine by me, a lot of designers would never have built anything if it weren't for them. Let's just acknowledge them for what they are please. And maybe every once in a while, something besides just cheerleading when you tell us about them.

I said I love your blog didn't I?

jujol,

Thanks for writing that comment. I read this blog regularly also, and often feel the same way…

Jujol, fair enough – I know there are many people would like to see a more "critical" approach on this blog, but I also think that many of those people mistake an attitude of personal negativity for architectural criticism.

The intrusiveness of this piece, for instance, is precisely why it's visually compelling for me, and the fact that it's inside a church certainly didn't escape my notice. A question for you might be: Why is introducing geometry into a church space "on the borderline of offensive"? After all, Baroque ornament itself is the presence of geometry – often quite large-scale – inside a church space; is the frivolous presence of excess surface area somehow against Christian principles?

For me, the stripped-down, abstract mathematical form seen here seems to be a very interesting variation on the Baroque interior it hangs within, like bare geometry itself bulging into the world through religious space.

I appreciate, again, that many readers would like me, at the very least, to pause every once in a while and point out at least some of the downsides of the projects I refer to, and to make it clear, in the process, where those projects have gone wrong. At the same time, though, I don't see how writing that this project is an "archithingie" would be enough to keep me interested in blogging about architecture in the first place.

Geoff, I'm sure you don't need me to tell you this but the interesting thing about this blog is the way you use architecture as the starting point for imaginative speculation and you also highlight architects who are doing that.

It's like a type of pure architectural research and I personally admire it very much because of my belief that it highlights the way cultural memes adapt and evolve. It also in its way participates in that process of adaptation. Cultural adaptation is now fundamental to human survival given the way our memes have led us to the brink of extinction.

Don't let sourpusses like jujol or norbert put you off. If they just want architectural porn there is plenty of that to be found elsewhere.

It's an interesting occupation of the negative space, but it somehow looms a little too large (pun intended) to have visual appeal in this particular venue. I really wonder what the folks that attend that church regularly have to say about it. For me it invokes a "the sky is falling" feeling rather than anything charged with a purpose, spiritually or otherwise.

This reminds me of Frei Otto's upside down chain models which he used to design his tensile fabric structures back in the 1960's.

As JHF points out, this is how Gaudi worked: an inverted model of the Sagrada Familia hangs in exhibition in the basement of the cathedral. As the real building above is still in progress, it's very much a model of an imagined building.

First of all, thanks for posting this, including the behind-the-scenes photos. Very interesting!

While I find the installation intriguing, in some ways beautiful, and very interesting to "watch" being mounted, I find the piece itself oddly unsatisfying – the shapes we're used to perceiving in domes are spherical and feel somehow complete, even though the viewer has to invent the invisible bottom half when looking up at one.

Despite the light materials and elegant construction, this feels droopy, off-kilter and therefore invasive – although I'd hesitate to say "obscene", as one reader did, except in its vague resemblance to a nut-sack.

Is it permanent? (the installation, not the resemblance).

I'm not sure it's just insubstantial naysaying to have reservations over this design, it really doesn't seem to be as effective as it could be, being neither quite an inverted dome or quite an inverted spire, and the potential this has for negatively impacting the principal use of the building is a significant problem.

Nonetheless, it is certainly a brave and spectacular piece which on balance – I feel – succeeds more than it fails.

Oh… it's a giant net to catch all the childrens.

Cool, Jeroen – thanks.

Thanks from me, as well, Jeroen.