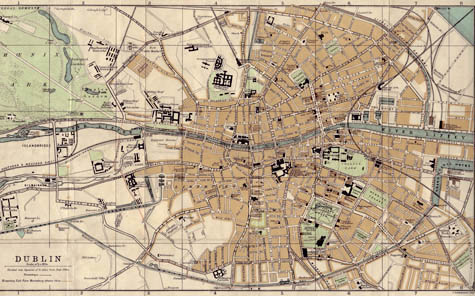

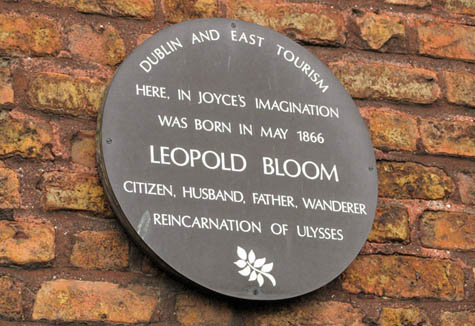

Yesterday, as James Joyce fans will know, was Bloomsday: June 16th. The day Leopold Bloom made his famous walk around Dublin in Joyce’s 1922 novel Ulysses.

[Image: Street map of Dublin].

[Image: Street map of Dublin].

Ulysses – considered something of the ultimate in literary modernism, as much for its mythical remaking of everyday life as for its often impenetrable abstraction, presaging Joyce’s later linguistic kaleidoscope, Finnegan’s Wake – was, for me, utterly transformed when my brother suggested that it was actually an attempt at descriptive realism.

That is, should you want to describe a man’s walk around the city in as detailed and realistic a way as possible, capturing every minor event and instant, then you would have to include the circumstances of that walk in their often bewildering totality: every fragmentary thought process, directionless flight of fancy, and irrelevant detail noticed along the way, via a million and one dead-ends. Things remembered and then forgotten. Deja vu.

That daydream you had early today? That was, Ulysses suggests, part of the infrastructure of the city you live in.

The city here becomes a kind of experiential labyrinth: it is something you walk through, certainly, but it is also something that rears up mythically to consume the thoughts of everyone residing within it.

To say that Ulysses, then, is one of the most realistic urban novels ever written surely sounds like a joke to anyone not connected to academia – yet, once the apparent absurdity of such a statement wears off, it seems utterly ingenious.

After all, how do you map the city down to its every last conceivable detail? And what if cartography is not the most appropriate tool to use?

What if narrative – endlessly diverting narrative, latching onto distractions in every passing window and side-street, with no possible conversation or observation omitted – is the best way to diagram the urban world?

In such a constellated wealth of minor points, “realism” becomes a useless haze – like listening to every conversation at a party simultaneously. And that’s before you add internal monologues and descriptive details from the pubs and sidewalks all around you.

In any case, there are many secondary points to make here. For instance, I’d actually suggest that the narrative position just outlined actually describes not a person at all but a surveillance camera – that is, the Ulysses of the 21st century would actually be produced via CCTV: it would be Total Information Awareness in narrative form.

But the whole point of this post was actually to ask two things:

But the whole point of this post was actually to ask two things:

1) What if Ulysses had been written before the construction of Dublin? That is, what if Dublin did not, in fact, precede and inspire Joyce’s novel, but the city had, itself, actually been derived from Joyce’s book?

At the very least, this would be an awesome proposition for a design studio: read Ulysses and then design the city it describes… The differing responses would be fascinating.

Further, this raises the question of whether a city has ever been built, directly inspired by a work of fiction. Of course, you could stretch the term fiction a bit, and say that those fundamental fictions of a nation’s founding myths might have inspired a city – or an historic preservation district – or perhaps you could even say, as if channeling Michael Sorkin, that the city’s zoning code is itself a monumental act of narrative modernism.

But what about an actual novel? If you can take, say, Moonraker by Ian Fleming and turn it into a film – that is, Moonraker, directed by Lewis Gilbert – then could you also take a novel – here, Ulysses – and turn it into a city?

2) If you fed Ulysses into a milling machine – that is, if you input not a CAD file but a massive Microsoft Word document containing the complete text of Ulysses – what might be the spatial result? Would the streets and pubs and bedrooms and stairwells of Dublin be milled from a single block of wood?

What if you fed Ulysses through a 3D printer?

Oddly, I’m reminded here of something that has long fascinated me: quipu, the so-called knot language of the Inca. Quipu, to make a very long story short, is a way of braiding strands of animal hair or colored yarn together, using specific types of knot; these knots, arrayed in specific orders, thus communicate things to others – whether that’s accounting information or perhaps even cultural myths.

It was a form of writing, in other words, although its words were 3D shapes.

As a brief aside, the possible paranoias of a quipu translator have always seemed particularly stunning to me: for instance, someone over-immersed in the world of Andean knot-languages becomes convinced that, in the drooping symmetry of a basketball net or in the shoelaces of strangers walking past on the street, there might be written messages: epic poems, secret codes, unintended diary entries.

Instead of Freudian dream-analysis, you perform quipu knot-analysis, even examining the micro-fibers of strangers’ clothing for hidden meanings… (It’s worth mentioning that this exact idea actually appears in the unwatchably annoying film Wanted).

In any case, I mention quipu here because I can’t even believe how cool it would be if 3D printers might someday be used to create word-objects: little amorphous and abstract three-dimensional shapes that aren’t just works of art, they are a new form of writing.

Like quipu, they are 3D linguistics: words in space.

The idea here that all those high-end design items you see lining the shelves of boutique shops in downtown Milan or Moscow or Manhattan are actually strange new, highly literal forms of communication, makes the mind reel.

Spy films of the future! MI6’s man in Havana goes into a specialty cookware shop where the salt and pepper shakers are not at all what they seem…

Or, inspired by Alfred Hitchcock, the FBI begins leaving little figurines in empty hotel rooms, knowing that the next guest will be an undercover informer – and those abstract statuettes left behind in the cupboard actually encode the next location of rendezvous…

And so on.

So the point of this long tangent is this: if you fed Ulysses through a 3D printer, what might the resulting shapes be?

What if the unexpected blobs and shapes could be considered a translation of the novel?

[Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in Dublin].

[Image: Historical maker for the birthplace of Leopold Bloom in Dublin].

Inspired by Bloomsday, then, it seems well-timed to ask not only how our cities can best be mapped – and if narrative is, in fact, the ideal cartographic strategy – but what other physical possibilities exist for narrative expression. Put another way: what if James Joyce had been raised in an era of cheap 3D printers?

After all, given the possibilities outlined above, we might even someday be justified in concluding that Dublin itself is a written text, and that Ulysses is simply its most famous translation.

This post reminded me of the chapter of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities that tells of a city built based on dreams of pursuing a woman through winding streets. But isn't this all well explored in the concept of "psychogeography" – the interaction of the built environment with the inner narrative?

I strongly recommend you two sci-fi books, about language and environment construction: Babel-17 by Samuel Delany, and The Embeding, by Ian Watson.

As I recall, in the wonderful "Intercities", Stefan Hertmans mentions that though Ulysses is set in Dublin, Joyce was actually living in Trieste when writing it and that, according to Hertmans, traces of that other city can be found throughout the book.

Which raises an interesting question; If Dublin were recreated from Ulysses, would we find in the street map bits of Trieste? Wander away from the banks of the Liffey and find yourself on the Via Machiavelli?

And further; How much of any city could be reproduced from a human-hand source without accidentally incorporating fill-in data from any other city known to the author/architect?

And finally; What does this say about our (actual) experience of (actual) cities?

Thought provoking. Cheers, Geoff.

To the suggestion that ordinary objects may be forms of communication- I would like to ask (or state) isn't that the point of design? I believe that it is. While they don't all communicate in verbal languages -or knots for that matter- though some can talk at us, when we experience an environment don't we read and understand the space and its inhabitants based on the objects and the placement of those objects surrounding us?

Then wouldn't the only question in design be: is the space or object effectively communicating with its intended audience.

To tie this back to Ulysses- maybe narrative is the most effective way in order to understand an environment but those pieces of the city that cause us to react are going to be different for everyone. Thats was so great about these experiences they morph with us and constantly bring a new experience and will never be as flat as any map no matter how 3D it is.

I'll echo Will's mention of psychogeography: the Songlines of indigenous Australians refer to geographical landmarks or other navigatory aids.

I had a little city map as my only guide during my first read of Ulysses. It was mostly useless in so far as I had never visited Dublin; for it could have been anywhere in the world, particularly as the myriad themes and abstractions were universal in nature.

If you plot out the novel's geography, it reveals a sort of cross with *I think* NE–>SW and SE–>NW axes [Jorn Barger has a lot of this stuff on his sprawling Joyce site], symbolic of the christian/catholic cross of course.

I don't know that you could – as Joyce jokingly or perhaps even seriously opined was possible – reconstruct Dublin, if it was destroyed, from Ulysses alone; I don't know that narrative by itself (in this case anyway) is sufficient to spatially arrange it all, or even just the path travelled on that day in the novel. The narrative gives untold depth to the map though; so I think it's fairer to say that narrative allows for unlimited dimensional extension from a mathematicographical 2-D grid.

Aside from the though-provoking re-creation of a dream landscape Dublin/Trieste in Ulysses, the idea of a Dublin re-created from Ulysses is an interesting concept.

The Dublin of Leopold Bloom is in some ways long gone. The Easter Rising of 1916, centred around the General Post Office on O'Connell Street, laid waste to a large swath of Dublin's core as the British artillery whaled away on the GPO and other rebel-held buildings in central Dublin. The city was also damaged during the Anglo-Irish War of 1920-1 and the Irish Civil War of 1922-3, to say nothing of rebuilding, renovation, and gentrification projects around the core of the city and the re-making O'Connell Street to reflect the grandiosity necessary for a capital city.

But, Geoff, you bring up a larger issue I've been contemplating of late, which is the reconfiguration of the urban landscape in fiction: how do authors tailor and alter the landscape of the city in their fiction? How do their characters use and exploit that landscape? And so on and on. I am working (slowly) on a piece along these lines for the CTlab.

Joyce not only imagined that you could recreate Dublin from the text of Ulysses but that it would be Dublin on that very day, in 1904 Bloomsday. After all cities do change form with every day. Having lived in Dublin I do find that the book has the ability to transport you to particular places in the city, i.e Sandymount Strand. In a way that other fiction just cannot. Its as if Leopold's stream of conciousness becomes your own. Which is quite remarkable.

i like the idea that joyce's dublin was a snapshot of a character, like a family photo. that this "picture" could then be used to then chart the growth and mutations of the city as it has climbed into adolescence and adulthood or however one wants to extend the metaphor. along with these 3d maps of the cities, we would need have a secondary map that charted the growth, mutation, development, decay, reclamation etc of the city, just as humans go through all those phases. just a thought.

but also wanted to say, i stumbled across your blog about a month or two ago and have instantly become quite smitten. well articulated ideas about things i had not idea existed, let alone be interested in. thank you for providing something so thought provoking.

Cities based on books? do religious texts count? seems like teotihuacan would fit the bill.

Great post Geoff! It is nice to see Ulysses situated in relation to a world of making, of machines for building. Penelope was of course a weaver, what other actions can we queue up? 🙂

I don't have too much to add other that to point out another recent (2008) response to Bloomsday worth checking out is Conor McGarrigle's Joyce Walks which was part of the last issue of Vague Terrain. Conor's project is a post-Google, crowdsourced reconsideration of the annual event.

Reminds me of a studio project I once had where we were given a chapter from Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities and were given the task of creating the city not only described but we envisioned after reading it.

this might interest you:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altneuland

Theodor Herzl published a book in 1902, for a city that would be founded 7 years later. I haven't read it myself, but now I might just will.

Oh, and (having just seen this comment) on religion and cities based on books… I'd start by going a step further and start wondering about the city as imagined by books? But regardless, maybe the closest religious equal to Ulysses is the King James Version of Ezekiel (most of the last third in particular).

Irrespective of Judeo-Christian belief, it's a truly bizarre/fantastic image, and it's post-history has some of the most fascinating responses around (alchemy, Freemasonry, the Dome of the Rock & Constantine's Holy Sepulchre…. and one day a Kentucky theme park). And that's not even getting into the text itself…

This is such a great post; I wish more architects would pick up on this and spend time thinking about Ulysses.

I'm really surprised there isn't a surge in comments on this thread every Bloomsday to B-day+/-3. In a way though, there's something really comfortingly anonymous about submitting a comment 2 years after the fact. Not to mention how it undermines cyber-narcissism as it raises the mystery over if anyone will ever see it….

But anyone who's particularly intrigued by this post (and who has access to AD's archive) should have a read (or several) of Peter Carl's 'Type, Field, Culture, Praxis' in the Jan/Feb 2011 edition of Arch. Design. The article, I believe, goes a long way towards identifying 'city' and 'urban' as they lie and act even beyond psycho/mathematico geography (perhaps because they're identified as never fully identifiable?). The article also poses a significant challenge to discussing the city as a distribution of objects in space, even if one responds in the language of phenomenology rather than parametricism…

But for those who don't have immediate access, or don't want to wade through the whole essay, I'll quote the passage where the general thrust of Carl's argument is specifically relevant to Joyce (and anyone still recovering from Bloomsday hangovers in particular):

"Representations of cities by architects, planners or theorists rarely grasp typicality in [rich] terms. The standard of what is possible remains the Dublin of Joyce’s Ulysses (in particular, the necessity of crime, disease, ignorance or partial understanding, wit, conflict and so on, to the constant renewal in history of a civic ethos)."