Being inclined to spend time remembering things, I just made this map of my old flat in London. I lived there five years ago. How unbelievably bizarre it is to scroll around on that thing and remember street names, restaurants, transport routes to work…

Being inclined to spend time remembering things, I just made this map of my old flat in London. I lived there five years ago. How unbelievably bizarre it is to scroll around on that thing and remember street names, restaurants, transport routes to work…

In any case, the map also reminded me that my next door neighbor was a man named Aidan Andrew Dun. He was a poet; we spoke maybe two times, never in depth; and he was friends with Iain Sinclair.

Dun is the author of a long poem called Vale Royal, a kind of mytho-poetic walking tour, psychogeographically inspired by William Blake, exploring the region around King’s Cross.

I think it’s from Dun – but I don’t actually know; I just associate this with him – maybe I made it up? – that I heard a legend claiming that St. Pancras Old Church, stranded on its small hill behind the train stations next to the old London Hospital for Tropical Diseases, is actually the secret burial place of Christ.

The church, obviously, was built much later, as a means of marking the site – at the same time keeping silent its little secret.

And thus somewhere in the London soil, we’re meant to believe, is the body of Jesus Christ…

Imagine if it is there, though.

Imagine that it’s down there, talismanic, demagnetizing harddrives and affecting the moods of certain bus routes. You’re always happy whilst riding the 73 – and now you know why. Imagine that your Tube train just rattled past the body, lodged somewhere like a holy stone in London’s muddy undersurface, and a cold draft blew through the cabin. Imagine migratory birds flying east over the domes of churches three days before Christmas, then pulled north or south by some unseen point in the ground, that lost navigational burial that webs the earth with purpose.

Who knows.

Year: 2007

London 2090 A.D.

I seem to be under the influence of H.G. Wells this week, but something about the previous post reminded me of Wells’s old novel The Sleeper Awakes.

In that book we follow the shocked but exhilirated travails of a man who wakes up in London 200 years in the future – only to find that he’s become some sort of Messiah…

So the plot is not exactly interesting, but the book’s descriptions of architecture are extraordinary.

[Image: Cover illustration by Kate Gibb for The Sleeper Awakes].

[Image: Cover illustration by Kate Gibb for The Sleeper Awakes].

London, we read, has become a place of “vast and vague architectural forms.”

The book’s central character – the Sleeper, named Graham – looks around himself, spatially overwhelmed. He becomes aware of “balconies, galleries, great archways giving remoter perspectives, and everywhere people, a vast arena of people, densely packed and cheering.” Looking at the city, he says, is “like peering into a gigantic glass hive.”

His first impression was of overwhelming architecture. The place into which he looked was an aisle of Titanic buildings, curving spaciously in either direction. Overhead mighty cantilevers sprang together across the huge width of the place, and a tracery of translucent material shut out the sky. Gigantic globes of cool white light shamed the pale sunbeams that filtered down through the girders and wires. Here and there a gossamer suspension bridge dotted with foot passengers flung across the chasm and the air was webbed with slender cables. A cliff of edifice hung above him, he perceived as he glanced upward, and the opposite facade was grey and dim and broken by great archings, circular perforations, balconies, buttresses, turret projections, myriads of vast windows and an intricate scheme of architectural relief. Athwart these ran inscriptions horizontally and obliquely in an unfamiliar lettering. Here and there close to the roof cables of a peculiar stoutness were fastened, and drooped in a steep curve to circular openings on the opposite side of the space…

He begins to walk, touring the “great structural lines of the interior,” following “a narrow but very long passage between high walls, along which ran an extraordinary number of tubes and big cables.” From there, he passes over “strange, frail-looking bridges” through an “endless series of chambers and passages.”

[Image: An unrelated vision of London’s sci-fi future from Maurice Elvey’s 1928 film, High Treason, mentioned in Fantasy Architecture: 1500-2036].

[Image: An unrelated vision of London’s sci-fi future from Maurice Elvey’s 1928 film, High Treason, mentioned in Fantasy Architecture: 1500-2036].

Meanwhile, outside, the Thames has been drained, replaced with “a canal of sea water” fed by “vast aqueducts” that are “spanned by bridges that seemed wrought of porcelain and filigree.”

And the entire place runs on wind power:

He saw that he had come out upon the roof of the vast city structure which had replaced the miscellaneous houses, streets and open spaces of Victorian London. The place upon which he stood was level, with huge serpentine cables lying athwart it in every direction. The circular wheels of a number of windmills loomed indistinct and gigantic through the darkness and snowfall, and roared with varying loudness as the fitful wind rose and fell. Some way off an intermittent white light smote up and made an evanescent spectre in the night; and here and there, low down, some vaguely outlined wind-driven mechanism flickered with livid sparks.

Graham walks further into the strangeness, coming upon “a space of huge windmills, one so vast that only the lower edge of its vanes came rushing into sight and rushed up again and was lost in the night and snow.”

Standing beside a companion now, he tries to absorb all the things he’s seeing:

All about them huge metallic structures, iron girders, inhumanly vast as it seemed to him, interlaced, and the edges of wind-wheels, scarcely moving in the lull, passed in great shining curves more and more steeply up into a luminous haze. Wherever the snow-spangled light struck down, beams and girders, and incessant bands running with a halting, indomitable resolution, passed upward and downward into the black. And with all that mighty activity, with an omnipresent sense of motive and design, this snowclad desolation of mechanism seemed void of all human presence save themselves, seemed as trackless and deserted and unfrequented by men as some inaccessible Alpine snowfield.

Soon the man can’t take it anymore – and I love this line:

Then for a time his mind circled about the idea of escaping from these rooms; but whither could he escape into this vast, crowded world?

In any case, going back through Wells’s descriptions here I’m led to wonder aloud: Would architecture schools maintain higher student morale – and produce more interesting work – if they assigned reading material like this, instead of, say, A Thousand Plateaus?

Or does such a comparison collapse under further analysis? Surely such things could, and should, be assigned at the same time? They’re not mutually exclusive and may even benefit from one another’s company?

Stacked Cathedrals

[Images: The VitraHaus, a proposed collection showroom by Herzog & de Meuron; bottom photograph by Dezeen].

[Images: The VitraHaus, a proposed collection showroom by Herzog & de Meuron; bottom photograph by Dezeen].

This project made the rounds several months ago – and commenters the blog world over found it worthy of ridicule – but I’ve been reading St. Peter’s and so I have to wonder what would happen if you stacked cathedrals this way. A church made of bridges, all of which cross one another and lead back into themselves through cantilevered wings and side-chapels. Strategic elevators and light-wells punch voids through adjacent spaces, stretching into halls that lead outward as arches over rooms three floors below. There are vertical courtyards and consecrated spaces that defy gravity through self-buttressing, and even the smallest walls are part of the structure, bearing loads, part of the building’s strength and not mere decoration. What appear to be multiple buildings are really one – and other such obvious allegories. Etc. etc.

I can bear to see no more ruins

[Image: An aerial view of the bombing of Dresden during World War II; photo via Wikipedia].

[Image: An aerial view of the bombing of Dresden during World War II; photo via Wikipedia].

Toward the end of an article by H.G. Wells, discussed in the previous post here, Wells writes: “I can bear to see no more ruins” – and you’re with him. You think exactly.

You read that Wells is “sad and weary with a succession of ruins” as he tours the Alpine battlefields of the Austro-Italian war, that “insane escapade” at high altitude, just one part of a larger “history of colossal stupidities” wherein war is a folly, a blunder, a disaster, and you think, of course, how could anyone bear to see yet more scenes of destruction.

But then you read the rest of the sentence.

“I can bear to see no more ruins,” Wells writes, “unless they are the ruins of Dusseldorf, Cologne, Berlin…”

War always leads to yet more of itself later.

Here are Part One and Part Two of the Wells article, originally published in 1916 in The New York Times.

The bridged architecture of adjacent peaks and “the fallen man of letters”

[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of Aiguille du Midi, France (via)].

[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of Aiguille du Midi, France (via)].

On a purely superficial level, the above photograph of some Alpine resort in France reminded me of two comments left long ago on BLDGBLOG by a reader named Andy K.

Andy, responding to an old post called “Europe’s Geological Attics,” pointed out that “[t]he peaks of the Dolomites in Italy are full of bunkers and tunnels of various depths. They come from the bitter fighting that took place over the South Tyrol region in WWI.”

These “bunkers and tunnels of various depth” were, for the most part, constructed by and for the Alpini, Italy’s mountain warfare brigade, to aid in Italy’s war against the Austrians.

[Image: The fortified peaks of the Rotwand Summit, WWI].

[Image: The fortified peaks of the Rotwand Summit, WWI].

Today there are even some hiking trails – called the vie ferrate – that will take you up to these now abandoned structures embedded in the uplifted rocky surface of the earth, should you be willing and able to hike that far.

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

Limiting ourselves for the time being to Wikipedia, we learn that:

Until the end of 1917 the Austrians and the Italians fought a ferocious war in the mountains of the Dolomites; not only against each other but also against the hostile conditions. In the particularly cold winter of 1916 thousands of troops died of cold, falls or avalanches. At least 60,000 troops died in avalanches during the war. Both sides tried to gain control of the peaks to site observation posts and field guns. To help troops to move about at high altitude in very difficult conditions permanent lines were fixed to rock faces and ladders were installed so that troops could ascend steep faces. These were the first via ferrata.

Today, that entry continues, “[t]renches, dugouts and other relics of the First World War can be found alongside many [of these hiking trails]” – ascending deeper into the military history of Europe, by climbing up.

[Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

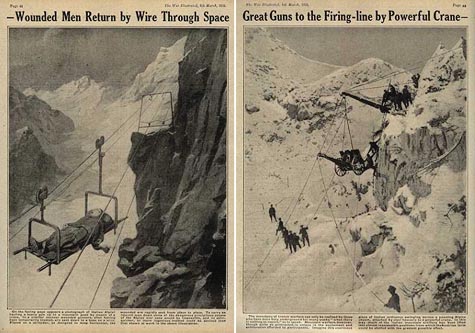

Of course, evacuating the wounded was also rather interesting; I was fascinated to see that “wounded men return by wire through space.”

[Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes; via].

[Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes; via].

Awesomely, sci fi author and war correspondent H.G. Wells even did some reporting on the matter.

For The New York Times, back in 1916, Wells wrote:

Mountain surfaces are extraordinarily various and subtle. You may understand Picardy upon a map, but mountain warfare is three-dimensional. A struggle may go on for weeks or months consisting of apparently separate and incidental skirmishes, and then suddenly a whole valley organization may crumble away in retreat or disaster.

Describing the Italy-Austrian mountain war as “among the strangest and most picturesque [battlefields] in all this tremendous world conflict” –

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

– in fact, he adds, the “fighting in the Dolomites has been perhaps the most wonderful of all these mountain campaigns” – Wells goes on:

Everywhere it has been necessary to make roads where hitherto there have been only mule tracks or no tracks at all; the roads are often still in the making, and the automobile of the war tourist skirts precipices and takes hairpin bends upon tracks of loose metal not an inch too broad for the operation, or it floats for a moment over a dizzy edge while a train of mule transport blunders by. (…) Down below, the trees that one sees through a wisp of cloud look far too small and spiky and scattered to hold out much hope for a fallen man of letters. And at the high positions they are too used to the vertical life to understand the secret feelings of the visitor from the horizontal.

One more long quotation – come on, how many of you knew that H.G. Wells was also a war correspondent? – because his descriptions of these mountain landscapes are just great:

The aspect of these mountains is particularly grim and wicked; they are worn old mountains, they tower overhead in enormous vertical cliffs of sallow gray, with the square jointings and occasional clefts and gullies, their summits are toothed and jagged; the path ascends and passes around the side of the mountain upon loose screes, which descend steeply to a lower wall of precipices. In the distance rise other harsh and desolate-looking mountain masses, with shining occasional scars of old snow. Far below is a bleak valley of stunted pine trees, through which passes the road of the Dolomites.

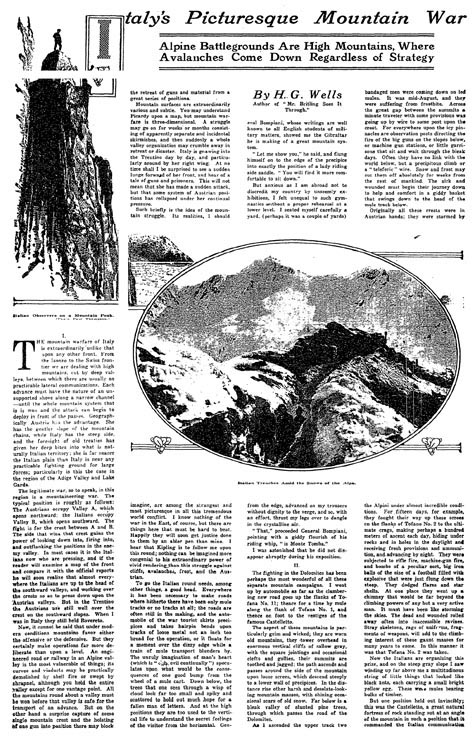

[Image: From The New York Times; I’ve also uploaded a much larger, readable version: click here to see it].

[Image: From The New York Times; I’ve also uploaded a much larger, readable version: click here to see it].

In any case, it’s the idea of the Alps being riddled with manmade caves and passages, with bunkers and tunnels, bristling with military architecture – even self-connected peak to peak by fortified bridges, the Great Mountain Wall of Northern Italy, architecture literally become mountainous, piled higher and higher upon itself forming new artificial peaks looking down on the fields and cities of Europe – that just fascinates me; not to mention the idea that you could travel up, and thus go futher into history, discovering that the past has been buried above you, the geography of time topologically inverted.

(Thanks, Andy K!)

From Beyond

In New Scientist this week we read that an underwater neutrino detector being constructed at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea is, “to physicists’ surprise,” also picking up signs of aquatic life:

Spanning 10,000 square metres of the Mediterranean seabed, the Antares telescope is designed to tell us about the cosmos by picking up signs of elusive particles called neutrinos, which fly thousands of light years through space. To physicists’ surprise, however, the underwater particle detector is also providing a unique glimpse of marine life.

From astrophysics to marine biology in a heartbeart.

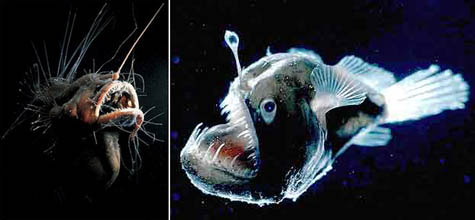

[Image: Courtesy of New Scientist].

[Image: Courtesy of New Scientist].

The huge underwater mechanism – called Antares – will not only give us more “information about where [neutrinos have] originated, such as the outskirts of black holes,” it will also register “waves of light” given off by “free-swimming bioluminescent bacteria” under intense benthic pressure at the bottom of the sea. Further, while peering into the outer dark, feeding currents of data into drone harddrives that think in slow algebras, unpeeling galaxial structure and calculating the future evolution of simulated stars, this machine amidst the shoals will also help solve “the mysteries of undersea storms.”

Living clouds of light swim past, colliding with particles as old as the universe – and the drowned antenna whirs on, detecting all of it.

Of course, all of this made me think of “From Beyond” by H.P. Lovecraft.

Of course, all of this made me think of “From Beyond” by H.P. Lovecraft.

In “From Beyond,” we encounter a narrator whose friend has 1) gone insane, 2) developed “baggy skin” with “hands tremulous and twitching,” and 3) built a machine, complete with moving crowns of glass bulbs and “a powerful chemical battery,” that will allow humans to “see and study whole worlds of matter, energy, and life which lie close at hand yet can never be detected with the senses we have.”

The man explains to our friendly narrator – who, for reasons of his own, has decided to visit this guy, overlooking his “repellent unkemptness” and “wild disorder of dress” – that:

The man explains to our friendly narrator – who, for reasons of his own, has decided to visit this guy, overlooking his “repellent unkemptness” and “wild disorder of dress” – that:

Within twenty-four hours that machine near the table will generate waves acting on unrecognized sense organs that exist in us as atrophied or rudimentary vestiges. Those waves will open up to us many vistas unknown to man and several unknown to anything we consider organic life. We shall see that at which dogs howl in the dark, and that at which cats prick up their ears after midnight. We shall see these things, and other things which no breathing creature has yet seen. We shall overleap time, space, and dimensions, and without bodily motion peer to the bottom of creation.

The machine awakens “dormant organs,” he says, so that we can see the horrors that surround us at every instant of existence, these ill-conceived but animate shapes that criss-cross endlessly through space.

Soon, the narrator shouts, there are “huge animate things brushing past me.” These are “disgusting” and “indescribable shapes” like “jellyfish monstrosities” that “flabbily quive[r] in harmony with the vibrations from the machine.”

Soon, the narrator shouts, there are “huge animate things brushing past me.” These are “disgusting” and “indescribable shapes” like “jellyfish monstrosities” that “flabbily quive[r] in harmony with the vibrations from the machine.”

The living shapes are even “semi-fluid and capable of passing through one another and through what we know as solids.”

Etc. etc. He ends up shooting the machine and his friend dies of apoplexy.

You can read the rest of the story here.

So what happens when scientists fully assemble this vast and sprawling neutrino detector at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, within sight of ruined arches onshore and Piranesian streetscapes, only to find themselves detecting, in a chaos of vibration and flashing light, previously unknown and hostile forms of maritime life?

So what happens when scientists fully assemble this vast and sprawling neutrino detector at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, within sight of ruined arches onshore and Piranesian streetscapes, only to find themselves detecting, in a chaos of vibration and flashing light, previously unknown and hostile forms of maritime life?

And what happens if that otherwise undiscovered life detects the machine?

Can BLDGBLOG retain the film rights?

The Property

There was an interesting article in The New York Times this week about “161,000 acres of highly prized Adirondack wild lands” that were purchased this summer by the Nature Conservancy.

The cost was $110 million – and the sellers had owned the land since the end of the Civil War.

[Image: The “View from Noonmark Mountain” by Robbie’s Photo Art, found via Flickr; this photo is simply for illustrative purposes: as far as I’m aware, it does not show the property discussed below].

[Image: The “View from Noonmark Mountain” by Robbie’s Photo Art, found via Flickr; this photo is simply for illustrative purposes: as far as I’m aware, it does not show the property discussed below].

These 161,000 acres, “considered the last remaining large privately owned parcels in Adirondack Park,” we read, “are an ecological marvel”:

containing 144 miles of river, 70 lakes and ponds, more than 80 mountains and a vast unbroken wilderness that only loggers and a few hunters have ever seen. The property also contains unmatched natural features like the blue ledges of the Hudson River Gorge, OK Slip Falls and Boreas Pond, with its stunning views of the Adirondack high peaks, which naturalists have dreamed of protecting for decades.

While the article is actually about what the Nature Conservancy might be forced to do next, in order to live up to its own purchasing agreement, what I find extraordinary is the idea that these 161,000 acres of “unbroken wilderness,” a long day’s drive from New York City, have only been seen by “loggers and a few hunters” since the end of the Civil War.

So what else is out there…? And do we know?

[Image: Two stitched panoramas of the Adirondacks: (top) Valley View Ledge” / (bottom) “View from Catamount Mountain, both by retropc, found via Flickr].

[Image: Two stitched panoramas of the Adirondacks: (top) Valley View Ledge” / (bottom) “View from Catamount Mountain, both by retropc, found via Flickr].

Absurd questions, of course: it’s New York state, not Borneo or even Utah – or Bosnia, for that matter – and so it seems relatively unlikely that some weird and amazing lost city or heretofore unknown species of hominid will be found out in the darkness by Nature Conservancy volunteers.

And yet I can’t help but think of vague, sci fi-like scenarios of undiscovered archaeological sites – civilizations no one even dreamed existed, thriving here on the North American landmass before ice ages came and scraped the place clean – or monstrous fossils lodged in lumps of exposed bedrock, weird marks in the sides of distant hills corresponding to no known period of the earth’s biological history… Crashed spaceships. The world’s largest cave system. Medicinal flowers.

And so on.

Anyway, there’s something about large, privately held plots of wilderness that absolutely fascinates me – and not because I advocate turning the public lands of the United States over to private interests, but because of what I might call the literary, even psychological, possibilities of owning wilderness.

In fact, I’m reminded of yet another New York Times article, this one about the large-scale private purchasing of former timber lands out west.

There is, we read, “a new wave of investors and landowners across the West who are snapping up open spaces as private playgrounds on the borders of national parks and national forests.” There are thus “private ponds” – and private rivers and mountains and gullies. In fact, there are “vast national forests, grasslands and wilderness areas that in Montana alone add up to nearly 46,000 square miles, about the size of New York State” – however, “in many places, the new owners are throwing up no trespassing signs and fences, blocking what generations of residents across the West have taken for granted – open and beckoning access into the woods to fish, hunt and camp.”

Then, surrounded by a few hundred acres of remote and unpopulated – and unpoliced – land, you start to do things… Gradually planning a bid for political sovereignty. Building things deep in the woods. Walking around alone at midnight, thinking about calculus, surrounded by 2000 acres of your own land.

This, in turn, reminded me of an old Clive Barker story called “Down, Satan!”

I may not have remembered the story correctly, having last read it in high school, but its premise is that a fabulously wealthy businessman decides to build Hell on Earth – literally to construct Hell – in order to summon forth the devil (or some such idea). He thus sets about designing and building a terrifying new complex full of torture machines and acid baths and vast graveyards somewhere on private land in Nevada.

At the end of the story, the police raid the place and the guy realizes that he has, in fact, summoned the devil to Earth – and it’s him…

[Image: “Serene View” in the Adirondacks, by |ash|, found via Flickr].

[Image: “Serene View” in the Adirondacks, by |ash|, found via Flickr].

In any case, we learn that these sorts of transactions, involving formerly public lands, are growing much more common – but also more complex and more ambitious. “Over the last 10 years,” we’re told, “at least 40 million acres of private forest land have changed hands nationwide.” 40 million acres! That’s very nearly the size of the United Kingdom.

Of course, the motivation behind all these purchases is not preservation – or even constructing Hell: it all comes down to logging. Even environmental advocates are now picking up their chainsaws.

In ways that would have been unthinkable only a few years ago, environmentalists and representatives of the timber industry are reaching across the table, drafting plans that would get loggers back into the national forests in exchange for agreements that would set aside certain areas for protection.

Both groups are feeling under siege: timber executives because of the decline in logging, and environmentalists because of the explosion of growth on the margins of the public lands.

(…)

Many environmentalists say they have come to realize that cutting down trees, if done responsibly, is not the worst thing that can happen to a forest, when the alternative is selling the land to people who want to build houses.

But surely “selling the land to people who want to build houses” is not the only alternative.

Surely someone with loads of money could finally do something interesting, for instance, putting aside the cocaine addiction and the personal fleets of Range Rovers and the Malibu mansions and buying land, buying lots of land, buying as many tens of thousands of acres as they can afford – and not developing it, not re-selling it, not clear-cutting it, not even necessarily preserving it, just doing something out there in their own private wilderness, whether it’s opening a system of public trails – or maybe you can subscribe to the land the way you subscribe to a magazine, and so you get access to new trails every few months – or building radio astronomical research stations, or a summer camp for landscape journalists, or the BLDGBLOG Academy, or a human clone farm, or whatever. Build a private cave. Who cares.

But, surely, with literally tens of millions of acres of land at stake here, and with more and more – and more – people becoming billionaires, let alone millionaires, someone with a little imagination will come along finally and do something interesting out there, away from the airports, alone in the darkness of North America, surrounded by maple trees, coming up with plans, changing history, supplying novelists with fodder for plots for decades to come.

Otherwise we’ll just build more houses.

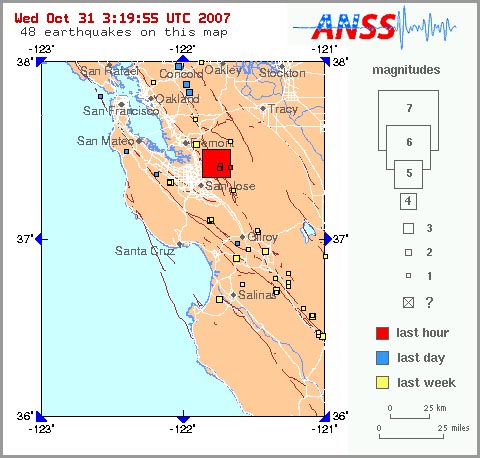

Event 40204628

We just had another earthquake.

We just had another earthquake.

The house jolted; the front door chain swung back and forth, tapping the doorframe; and I stood up, looking out the back window, realizing that if all hell breaks loose I’m really thirsty and I don’t have any bottled water. The jolting became a dull vibration, and then it ended. I sat back down on the futon.

It was a 5.6 on the Richter scale, and the epicenter was 5.7 miles beneath the Earth’s surface.

It was Event 40204628.

Earlier: Event 14312160

Spies, Light-Writing, and the Surface of the City

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

This morning’s post reminded me of a link someone sent in two weeks ago: Energie in Motion, a light-writing project by two guys in Germany.

Hey, little man! What are you doing outside by yourself? You look sad.

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

There’s no need to hide!

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

It’s just me…

For more images, stop by the Energie in Motion site itself. There’s even a short video you can watch of the men at work, writing with light in Munich and Hamburg, turning parking meters into robots and animating street signs with little glowing arms and legs.

It’d be interesting, meanwhile, if you could install some sort of moving light sculpture in the center of the city. The sculpture appears to be totally abstract: casually and randomly, it switches back and forth amongst various positions, spinning little lights around, making arcs, circles, hops, jumps, and flashes, all to no real purpose or design – but then someone accidentally takes a photo of it using too long an exposure…

The resulting images, developed back at home in a basement darkoom, reveal that the sculpture is actually writing things in space.

Like this:

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

[Image: By and via Energie in Motion].

It just requires an elongated present moment in which to read it.

Turns out it’s a new way for spies to communicate – and this random tourist with a camera has now uncovered a sinister plot…

Alfred Hitchcock directs the film version.

(Thanks, Joel D.! Vaguely related: Automotive Ossuary).

White Light

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio].

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio].

I stumbled on an old project from the summer of 2004 today, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio, called White Noise/White Light.

The project was on display in Athens during the 2004 Olympics:

Comprised of a 50′ x 50′ grid of fiber optics and speakers, “White Noise/White Light” is an interactive sound and light field that responds to the movement of people as they walk through it… As pedestrians enter into the fiber optic field their presence and movement are traced by each stalk unit, transmitting white light from LEDs and white noise from speakers below.

And though I wasn’t in Athens to see the thing in person, it certainly did photograph well.

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio].

[Image: White Noise/White Light, Athens, by Höweler + Yoon/MY Studio].

Juxtaposed with the Parthenon in the background, the effect, in fact, looks quite mesmerizing.

Electrical practicalities and issues of light pollution aside, it’d be nice to install something like this for a few nights along the rim of the entire Grand Canyon… Then fly over it in a glider, at 3am, taking photographs.

UPDATE: How strange: I came home from work today to find two copies of Architect magazine waiting for me in the doorway – and lo! On p. 49 of their September 2007 issue there’s nothing else but “White Noise/White Light” by Höweler + Yoon… Architect says: “The experience and publicity that Höweler + Yoon gained from the Olympics project have led to new commissions and further explorations in up-to-the-nanosecond lighting technologies.” Interesting overlap.

(Earlier: Archidose blogged it).

The Road

Flying into Vegas last night to speak at a conference hosted somewhere inside the Venetian Hotel by the Urban Land Institute, I read Cormac McCarthy’s recent novel, The Road. It’s a book I’d long wanted to read but kept putting off for some reason, and I’m glad I finally read it.

[Image: By Trevor Manternach, found during a Flickr search].

[Image: By Trevor Manternach, found during a Flickr search].

If you don’t know the book, the basic gist is that the United States – and, we infer, everything else in the world – has been annihilated in what sounds like nuclear war. But all of that is just background for the real meat of the book.

The Road follows a father and son as they walk south, starving, toward an unidentified coast. They cross mountains and prairies and forests; everything is burned, turned to ash, or obliterated. The father is coughing up blood and the skies are permanently grey.

Briefly, I’d be interested to hear, out of sheer curiosity, where other people think the book is “set” – because it sounds, at times, like the hills of New York state or even western Massachusetts; at other times it sounds like Missouri, Tennessee, parts of Mississippi, and the Gulf Coast; at other times like the Sierra Nevadas, hiking down toward the rocky shorelines just north of, say, Santa Barbara. Sometimes it sounds like Oregon.

In any case, the only glimpse we get of the war itself is this – and all spelling and punctuation in these quotations is McCarthy’s own:

The clocks stopped at 1:17. A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions. He got up and went to the window. What is it? she said. He didnt answer. He went into the bathroom and threw the lightswitch but the power was already gone. A dull rose glow in the windowglass. He dropped to one knee and raised the lever to stop the tub and the turned on both taps as far as they would go. She was standing in the doorway in her nightwear, clutching the jamb, cradling her belly in one hand. What is it? she said. What is happening?

I dont know.

Why are you taking a bath?

I’m not.

After this, the landscape outside is described as “scabbed” and “cauterized,” heavily covered in ash.

McCarthy memorably writes: “They sat at the window and ate in their robes by candlelight a midnight supper and watched distant cities burn.”

The wife soon gone – indeed, she’s only ever present through flashbacks – the father and son stumble south pushing their food supplies, a few toys, and some “stinking robes and blankets” in an old grocery cart. They come across Texas Chainsaw Massacre-like houses, as some bands of bearded survivors have taken to cannibalism.

Interestingly, every house seems vaguely terrifying to the young boy in a way that the dead forests and dried riverbeds simply do not. Empty houses on hills with their doors left open.

So their journey down the road continues:

By then all stores of food had given out and murder was everywhere upon the land. The world soon to be largely populated by men who would eat your children in front of your eyes and the cities themselves held by cores of blackened looters who tunneled among the ruins and crawled from the rubble white of tooth and eye carrying charred and anonymous tins of food in nylon nets like shoppers in the commissaries of hell. (…) Out on the roads the pilgrims sank down and fell over and died and the bleak and shrouded earth went trundling past the sun and returned again as trackless and as unremarked as the path of any nameless sisterworld in the ancient dark beyond.

And then they approach what appears to have been a place actually struck by those distant concussions of sound and light, the perhaps atomic bombs of an unexplained war:

Beyond a crossroads in that wilderness they began to come upon the possessions of travelers abandoned in the road years ago. Boxes and bags. Everything melted and black. Old plastic suitcases curled shapeless in the heat. Here and there the imprint of things wrested out of the tar by scavengers. A mile on and they began to come upon the dead. Figures half mired in the blacktop, clutching themselves, mouths howling. He put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. Take my hand, he said. I dont think you should see this.

It’s a good book. It’s not perfect; a friend of mine quipped that it ends with “a failure of nerve,” and yet the nostalgic tone of the book’s final paragraph suited me just fine.

Which just leaves us, readers of things like this, preparing in whatever small ways we can to survive some undefined possible apocalypse of our own time here, the future politicized, the reservoirs drying, the religions hording arms and the oceans full of plastic. It’ll be interesting to see what happens next.

Cormac McCarthy: The Road