[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of Aiguille du Midi, France (via)].

[Image: At the self-interconnected heights of Aiguille du Midi, France (via)].

On a purely superficial level, the above photograph of some Alpine resort in France reminded me of two comments left long ago on BLDGBLOG by a reader named Andy K.

Andy, responding to an old post called “Europe’s Geological Attics,” pointed out that “[t]he peaks of the Dolomites in Italy are full of bunkers and tunnels of various depths. They come from the bitter fighting that took place over the South Tyrol region in WWI.”

These “bunkers and tunnels of various depth” were, for the most part, constructed by and for the Alpini, Italy’s mountain warfare brigade, to aid in Italy’s war against the Austrians.

[Image: The fortified peaks of the Rotwand Summit, WWI].

[Image: The fortified peaks of the Rotwand Summit, WWI].

Today there are even some hiking trails – called the vie ferrate – that will take you up to these now abandoned structures embedded in the uplifted rocky surface of the earth, should you be willing and able to hike that far.

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

Limiting ourselves for the time being to Wikipedia, we learn that:

Until the end of 1917 the Austrians and the Italians fought a ferocious war in the mountains of the Dolomites; not only against each other but also against the hostile conditions. In the particularly cold winter of 1916 thousands of troops died of cold, falls or avalanches. At least 60,000 troops died in avalanches during the war. Both sides tried to gain control of the peaks to site observation posts and field guns. To help troops to move about at high altitude in very difficult conditions permanent lines were fixed to rock faces and ladders were installed so that troops could ascend steep faces. These were the first via ferrata.

Today, that entry continues, “[t]renches, dugouts and other relics of the First World War can be found alongside many [of these hiking trails]” – ascending deeper into the military history of Europe, by climbing up.

[Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: A machine gun nest embedded in the Italian mountainside; found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

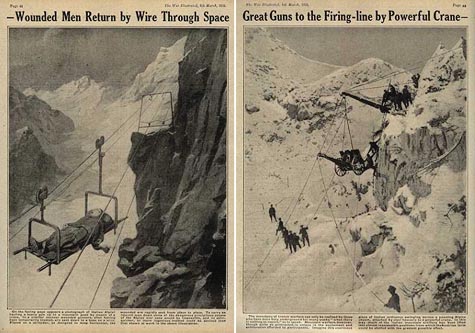

Of course, evacuating the wounded was also rather interesting; I was fascinated to see that “wounded men return by wire through space.”

[Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes; via].

[Images: Wounded men returning by wire through space as cannons are raised into place by cranes; via].

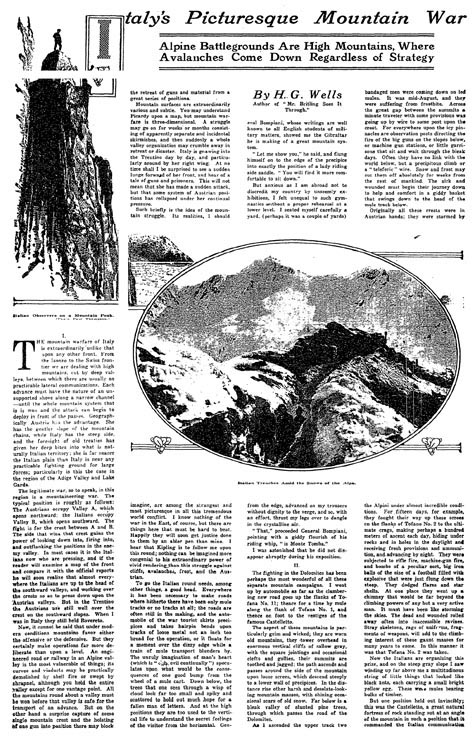

Awesomely, sci fi author and war correspondent H.G. Wells even did some reporting on the matter.

For The New York Times, back in 1916, Wells wrote:

Mountain surfaces are extraordinarily various and subtle. You may understand Picardy upon a map, but mountain warfare is three-dimensional. A struggle may go on for weeks or months consisting of apparently separate and incidental skirmishes, and then suddenly a whole valley organization may crumble away in retreat or disaster.

Describing the Italy-Austrian mountain war as “among the strangest and most picturesque [battlefields] in all this tremendous world conflict” –

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

[Image: Found via, copyrighted to, and courtesy of Dolomiti.org].

– in fact, he adds, the “fighting in the Dolomites has been perhaps the most wonderful of all these mountain campaigns” – Wells goes on:

Everywhere it has been necessary to make roads where hitherto there have been only mule tracks or no tracks at all; the roads are often still in the making, and the automobile of the war tourist skirts precipices and takes hairpin bends upon tracks of loose metal not an inch too broad for the operation, or it floats for a moment over a dizzy edge while a train of mule transport blunders by. (…) Down below, the trees that one sees through a wisp of cloud look far too small and spiky and scattered to hold out much hope for a fallen man of letters. And at the high positions they are too used to the vertical life to understand the secret feelings of the visitor from the horizontal.

One more long quotation – come on, how many of you knew that H.G. Wells was also a war correspondent? – because his descriptions of these mountain landscapes are just great:

The aspect of these mountains is particularly grim and wicked; they are worn old mountains, they tower overhead in enormous vertical cliffs of sallow gray, with the square jointings and occasional clefts and gullies, their summits are toothed and jagged; the path ascends and passes around the side of the mountain upon loose screes, which descend steeply to a lower wall of precipices. In the distance rise other harsh and desolate-looking mountain masses, with shining occasional scars of old snow. Far below is a bleak valley of stunted pine trees, through which passes the road of the Dolomites.

[Image: From The New York Times; I’ve also uploaded a much larger, readable version: click here to see it].

[Image: From The New York Times; I’ve also uploaded a much larger, readable version: click here to see it].

In any case, it’s the idea of the Alps being riddled with manmade caves and passages, with bunkers and tunnels, bristling with military architecture – even self-connected peak to peak by fortified bridges, the Great Mountain Wall of Northern Italy, architecture literally become mountainous, piled higher and higher upon itself forming new artificial peaks looking down on the fields and cities of Europe – that just fascinates me; not to mention the idea that you could travel up, and thus go futher into history, discovering that the past has been buried above you, the geography of time topologically inverted.

(Thanks, Andy K!)

There’s also the Swiss, who are still at it…:

http://photo-muse.blogspot.com/2007/05/leo-fabrizios-bunkers-and-new-stuff.html

http://www.leofabrizio.com/bunker/bunker_main.html

http://www.leofabrizio.com/newsite/selection_diplome/Bunkers.html

There’s also a fascinating episode of warfare in these mountains in the novel A Soldier of the Great War, by Mark Helprin. His character in this novel is a young Italian who is swept up into the Great War and ends up, eventually, in the alpini and assigned alone to a mountaintop post. He is attacked by the Germans and survives in one of the most harrowing segments of fiction I have ever read.

The Via Ferrata certainly is a great hike. Coming from North America, it can be very eye-opening to see how much life – from the beautiful farms in the valleys below to the shocking infrastructure of war at the height of the ridge – takes place in what, for me as a Canadian, ‘should’ be untouched wilderness. They’re different mountains over there, to be sure.

I did the descent through these fortifications last year. Easy but just astonishing to think of the poor slobs dying, not from enemy action but the elements mostly, for absolutely no purpose. Utterly fascinating. Not least because of the lodge at the base sells a wide variety of “hitlerwein” apparently catering to the Austrian fascist nostalgia market. My personal favorite was the Che Gueverra sparkling.

Great post. That is some amazing architecture.

I think the Indians and the Pakistanis have a very similar frontline on the Siachen Glacier, up in the Himalayas.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/siachen.htm

I agree with Tim, there are A LOT of bunkers in Switzerland. The Swiss army kept building them throughout the 20th century, knowing that they were completely worthless in case of a war. The bunker idea died in WWII.

Today all those bunkers are a big problem for the government because it’s very expensive to maintain them and as some are in the middle of towns and villages, it’s dangerous to just let them fall to pieces.

One truly hilarious aspect was that some of those bunkers where disguised as ordinary houses, villas or chalets. See here or here.

There was a special task force that decorated and painted those bunkers – often in some kind of meta-traditional-architecture of the region the bunker was built in.

Also wonderful (though I haven’t been there yet) is the Forte Malamot on the French-Italian border, near Mont Cenis. It was built in 1888 at an incredible 2914 meters.

For other relics of the war in the Dolomites see

http://addiator.blogspot.com/2006/08/lagazuoi-tunnels.html

http://addiator.blogspot.com/2006/08/monte-piana-in-dolomites.html

I suggest to you a great italian movie about first world war, “La grande guerra” and a tv program that focus the life in the trincea visible at:

http://www.rai.tv/mpplaymedia/0,,RaiTre-Ulisse%5E0%5E13375,00.html

all this stuff is in italian

If you’re interested in mountain worlds, I would highly recommend “Everything in its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood”, by famous Yale sociologist Kai Erikson. Although the book does not ostensibly deal with architecture, it lovingly explains the character and culture of the mountainmen in the Appalachians. Erikson paints such a myth-like world of these regions that I was always thinking about the book during my architecture studio courses.

I am surprised these are not mentioned in one of my favorite books, “The Architecture of War” by Mallory and Ottar.

I have a small collection of books about military architecture, which often unwittingly resemble 18th century follies in more ways than one.

To Mike Mahaffie – Just wanted to thank you for your mention of Mark Helprin’s book. Your comment intrigued me, and I got a copy of the book from the library the next day. During the time I read it, my daughter was born – between that event and the incredible writing/story of Helprin I was completely blown away. I’m now reading more of his stuff… And all that beauty came my way because of you, and BLDGBLOG. Thanks so much to you and to Geoff.

Congratulations, Larry! I’m glad you are enjoying Helprin and I know from personal experience that having a daughter is one of the greatest, and most rewarding, challenges a man can face.