[Image: “The Polecat UAV is pictured flying at 15,000 feet by a chaseplane. Polecat’s airframe was ‘laser printed’ rather than machined.” New Scientist Tech].

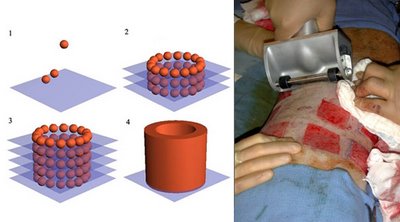

The same week we found out that jets of the future will be made with plastic, we also read that the U.S. military has been working toward printable airplanes – unmanned drones made by “rapid prototyping.” As New Scientist Tech reports: “In rapid prototyping, a three-dimensional design for a part – a wing strut, say – is fed from a computer-aided design (CAD) system to a microwave-oven-sized chamber dubbed a 3D printer. Inside the chamber, a computer steers two finely focussed, powerful laser beams at a polymer or metal powder, sintering it and fusing it layer by layer to form complex, solid 3D shapes.”

Of course, 3D printing is nothing new; several months ago, for instance, just about everyone in the universe learned that 3D buildings and cityscapes can be printed using images from Google Earth.

Even more strangely, you can also print fully-functioning body parts using “droplets of ‘bioink’,” which are “clumps of cells a few hundred micrometres in diameter.” In other words, if you “alternate layers of supporting gel, dubbed ‘biopaper’, with the bioink droplets,” and if you “build tubes that could serve as blood vessels, for instance,” then, through bio-printing, these will become the “successive rings containing muscle and endothelial cells, which line our arteries and veins.”

This Frankenstein-meets-Hewlett-Packard technology can be used to “print any desired structure.” Indeed, there are now “printing heads that extrude clumps of cells mechanically so that they emerge one by one from a micropipette. This results in a higher density of cells in the final printed structure, meaning that an authentic tissue structure can be created faster.” (What about a photocopier?) Finally, skeptics will benefit from learning that “cells seem to survive the printing process well. When layers of chicken heart cells were printed they quickly begin behaving as they would in a real organ. ‘After 19 hours or so, the whole structure starts to beat in a synchronous manner.'” (A bit more on this here).

The Oliver Twist of tomorrow, then, will be a poor boy, printed in obscurity…

So the question naturally arises: what if you were to combine all these? You’d get a vast, self-printing city-organism, whose skies are criss-crossed with machine-birds of prey; when buildings reach the age of senility, forgetting how many floors they contain, they are melted down into rivers of ink and pooled in living reservoirs to be printed once again; molds and fungi and architectural infections bloom, growing atop one another till new parasite structures form, small Gothic rooms in which the homeless live.

All of which reminds me, somewhat disjunctively, of the following rather unoriginal statement: the default condition of all literary genres will soon be science-fiction. You simply will not be able to write about the world without incorporating these weird new technologies.

Science-fiction and social realism will become one and the same thing.

Look at the recent genre-defying work of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michel Houellebecq, David Mitchell, Rupert Thomson, Alex Garland; soon even Ian McEwan will be writing sci-fi. Note, as well, that whilst mainstream American literary novelists appear increasingly incapable of doing anything other than reimagining their own national past – Philip Roth, say, or the forthcoming Thomas Pynchon – as if endlessly recycling historical micro-narratives will result in something new – Anglo-European fiction appears to have accepted, with great success and enthusiasm, the futurist inclinations already so obvious in everyday life.

To be rather broad here – for instance, does Michael Cunningham invalidate my argument? do I even have an argument? – it seems that while British fiction in particular has already accounted for the slippage of contemporary life into sci-fi, even welcoming this phenomenon with a newfound literary ambition, mainstream American fiction is content simply to enroll itself in unnecessary MFA programs, writing 800-page novels about family farms, the period between WWI and II, shopping, or the supposedly “atmospheric” end of the 19th century.

Run-of-the-mill student architectural proposals are already more stimulating than most of today’s American novels. Architectural proposals have ideas.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world has already discovered the future, and it’s no real wonder that the U.S. publishing industry is in the midst of a kind of slow financial crisis. In fact, you only have to look at the ongoing revival of interest in Philip K. Dick – sci-fi novelist and volunteer FBI informant – to see that Americans don’t exactly lack a literary taste for the future; it’s just that all the wrong novels keep getting published here.

In any case, there are a million exceptions to this argument; feel free to rip it apart. For example, where does The Da Vinci Code fit in all this? Etc. etc.

great post geoff,

and i agree that the line between imagined possibilities and real world research labs is growing very thin.

however if –

“the default condition of all literary genres will soon be science-fiction. You simply will not be able to write about the world without incorporating these weird new technologies.”

Does this not mean that science fiction has only grown lazy? That it needs to up the intensity of its invention?

I wouldn’t say that sci-fi is losing its futurist edge – perhaps some individual authors are – but simply that the boundaries between conventional narrative genres are changing. Of course, this is always true, more or less – if a character in a 1950s social realist novel had used a cell phone, for instance, it would have been considered a science-fiction novel. And yet that also supports my larger point, which is the science-fictionalization of everyday life. So none of this is limited to our era – or, certainly, to me: this isn’t a very original analysis, and I’m not the first person to say it. But it does seem to be more and more the case that everyday life is filled with technological and scientific novelty, and, therefore, that mainstream literary fiction’s ability to maintain a distance between itself and science-fiction will gradually disappear. Or a distance between itself and the genre that is currently known as sci-fi, I should say.

A purely sociological observation, then, and to rehash something from above, is that British fiction in particular seems to have made this leap already, to have accepted the fact that everyday life is now all but sci-fi. You can pick up any group of 3-for-2 books at Waterstone’s and find at least one book – or even several – that isn’t afraid to imagine the immediate future. Fly to the US, then, and walk into Barnes & Noble, and it seems, on the contrary, that every mainstream American novelist is simply terrified of even mentioning the future, and so all American novels now seem to consist of nothing but reimaginings of WWII from the perspective of a housewife, or a new look at growing up on a family farm in southern Illinois in the late 1800s, or the forthcoming (and completely unnecessary) sequel to Civil War-era Cold Mountain, or an atmospheric exploration of turn-of-the-century Boston and how somebody did something there to start a business or get married. And, frankly, it really shouldn’t surprise anyone that American fiction is no longer selling very well.

More to the point of your question, however, I assume that there’ll always be truly crazy science-fiction out there, books that imagine situations and technologies and spaces and personalities that will never happen – in many cases because they’d be physically impossible. So the genre itself isn’t being diluted, or threatened. Though, yeah, I would say that some authors need to step on the accelerator a little bit, and find some new ideas. But, really, it’s this kind of subtle, ongoing creep of science-fictional detail into our everyday lives that seems interesting to me.

One further note: you can, of course, write a social realist novel without ever mentioning, say, printable airplanes, and so it’s simply not true – as I say above – that all novels in the future will be science-fiction. Perhaps I could say instead: all interesting novels in the future will have a slight tinge of sci-fi… But even that’s an over-statement. In any case, it seems that British fiction now leads the way in this regard, leaving U.S novelists simply to stare, almost pathologically, at fading photographs of 19th century Americana. As if no one is quite sure how we got to this point in the first place.

Of course, I’m also just revealing my own prejudice for the future, and may have no idea what I’m talking about.

Geoff, thought you might want to see my post on the Polecat and the RP approach at my blog AeroGo.

Thanks, Gordon. Lots of info there. See also Defense Tech.

It seems like this discussion is ignoring the gleaming, titanium-clad elephant in the corner: Namely, that it has bee some time since Americans expressed their view of the future through the medium of the novel. With a few exceptions (Jonathan Lethem for one), novels have become the medium for looking back, while films and video games have created the future.

I think it comes down to the fact that there is a huge generational and gender gap in the reading population. Men between 10 and 30 are the most likely to be future-obsessed, and also the most likely to get their stimuli primarily through movies and the web.

If the British (and Canadian?) authors are still writing relevant science fiction, perhaps that is because Dreamworks and Pixar are in the US. (remember, Aardman Studios and even the Henson puppet shop are in England.)

Interestingly, the American science fiction author whose futurist paranoia has most become real – Philip K. Dick – is now the hottest commodity in Hollywood.

Have you guys heard about the laptop – mind connecting devise?

http://www.wired.com/news/technology/medtech/0,71364-0.html

on the lighter side of things:

http://www.npr.org/templates/rundowns/rundown.php?prgId=35

(click on the “Listener Limerick Challenge”)

Great post as always Geoff…

q

A really interesting conversation about the future of American fiction. I’m particularly struck by the idea that authors won’t be able to write about social realities without making reference to technology. One novel that seems to me to do this amazingly well in overcoming historical fiction’s traditional limits by using SF as a metaphorical tool is Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin, but then she’s Canadian, so point proven about US writers.

I do wonder, though, about writers who are tackling the portrayal of those portions of the population who have little or no access to modern technologies. It may still be true that most of them are not strictly “American” writers (I’m thinking particularly of Uwem Akpan, who has had two stories published in the New Yorker this year, but I think there are other writers as well who are trying to deal with visions of the future by looking at people who are disenfranchised (from technology, politics, mainstream society) in the present. And I’m also thinking of your recent interview with Mike Davis about Planet of Slums, Geoff. There are some writers who are trying to interrogate the massive inequalities in the world without reference to tecchnology at all, because most people still don’t have any. And of course two who immediately come to mind are also not American: the Indian novelist Rohinton Mistry and, in a very different (and very popular) way, Alexander McCall Smith. This isn’t to say that SF isn’t a better/more interesting way to do it, just different. I loved Specimen Days, which I think got crappy reviews because critics are totally out of touch with and prejudiced against SF. Same reason Battlestar Galactica didn’t get more Emmy nominations.

So yeah, most American fiction writers are too trapped in their own little Wisteria Lanes of middle-class angst, but one other point I’d like to make is about fiction (historical or otherwise) that uses magical realism as an alternative to another way of understanding the world (pure introspection–boring! or SF). I’m thinking here of recent novels I really love like Charles Baxter’s The Feast of Love and Emily Barton’s Brookland (to be fair, I’m only halfway through that one). It seems like to deal with the overwhelming nature of the future, one interesting way to explain the past and to figure out how we got here is to do what great science fiction does anyway: make you believe it could happen. Whether this happens through “magic” or through technology may be a moot point. That this rationalization of imagination may be the same impulse that eventually leads to the discovery of printable airplanes seems the interesting thing. And I think American consumers would buy it at the same rate they’re currently buying non-fiction descriptions of the discovery of almost everything if only it were marketed (and believed in by the critics) in the right way.

I’d venture a guess that the best writing doesn’t need to make reference to technology, and that some writing that refers to technology will be good for the way it relates our pre-cyborg selves to a world where it’s increasingly necessary to be more than human. I would also venture that, at best, literature involving technology is effective for its metaphorical capacities, its ability to illustrate or clarify subjective relationships, feelings, etc.

Starrykick – I think we’re on the same page, actually, because: 1) I was thinking about Margaret Atwood when I wrote the post. I didn’t mention her, though, because she’s really been writing sci-fi, or at least sci-fi-like novels, all along; my point, rather, was to point out how non-genre, mainstream novelists are discovering the porosity of social realism, in other words small trickles of science-fictional reality have begun to invade their writing. So mainstream writers are going sci-fi, but only inasmuch as they want to maintain a kind of referential accuracy in their descriptions of things.

Cloning (Ishiguro), space travel (Garland), future dystopias (Thomson, Mitchell), etc. I’m interested in the fact that if the everyday lived reality of the planet – whatever that means, and knowing full well that “everyday lived reality” is a phrase wide-open to academic critique – is described in a novel, then that novel reads like sci-fi. This has arguably been the case at least since the industrial revolution, though surely a truly accurate description of an imperial Roman feast under Caligula would have verged on sci-fi? Every era has its own science fiction.

Anyway, 2) The First World/Third World divide also came to mind while writing the post. However, if you look at something like The Constant Gardener, or just an annual report from Human Rights Watch, you see that poor villages and poor nations throughout the world are constantly brushing up against these almost surreal installations of First World medical/technological/political avant-gardes.

Cell phones are ubiquitous. Heavy weaponry is readily available. Then some American NGO flies in on a repurposed military helicopter, bringing in stem-cell treatment – and you continue that description just a little bit more, add a few more details, and you’re brushing up against sci-fi. Via social and geopolitical realism.

The other thing that fascinates me, meanwhile, something that will no doubt show up on BLDGBLOG or in some article somewhere, is how climate change is doing the same thing to surrealism. In other words, you write a novel or make a film and you say it’s snowing in Mexico City or that there’s a hurricane bearing down on Paris or there are palm trees growing in Toronto and parrots are flying tree to tree – but you’re not Jean Cocteau (or a sci-fi novelist), you’re simply documenting the socio-terrestrial effects of climate change. A tornado in Berlin, scattering sub-Saharan seeds that then wipe-out the local fauna, Africanizing Prenzlauer Berg.

What’s amazing is that things like that are already happening. Not tornadoes in Berlin, but these surreal biological displacements that, 100 years ago, would have sounded like an image by Max Ernst. A foot of snow in LA.

Anyway, blah blah blah.

And, David, I’d simply add that the popular turn toward video games and films in the US, looking for visions of the future, only proves that Americans still want models and images of the future – and that American novelists have failed to provide it for them.