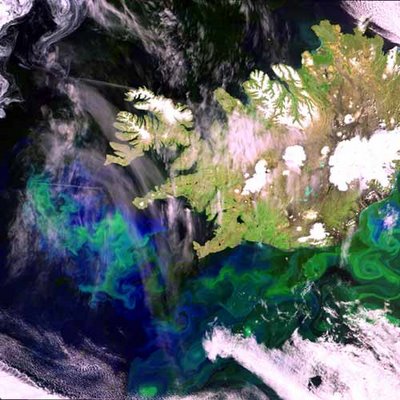

[Image: Here we see phytoplankton illuminating the Denmark Strait, forming solar-mineral arabesques, glowing traces. “While phytoplankton are tiny taken by themselves, together they can cause color shifts in ocean water, which in turn is detected by orbiting spacecraft.” Next, you build triangular frames, squares and circles afloat on the ocean – then fill them all in with phytoplankton: a sea of shining geometry. Cubes of light cast adrift across the North Sea, photographed from below by divers. Courtesy European Space Agency].

Month: May 2006

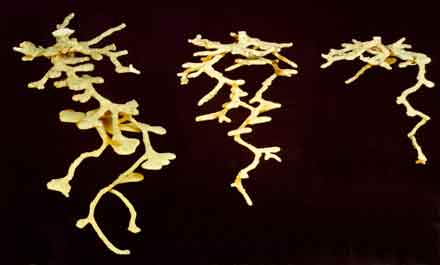

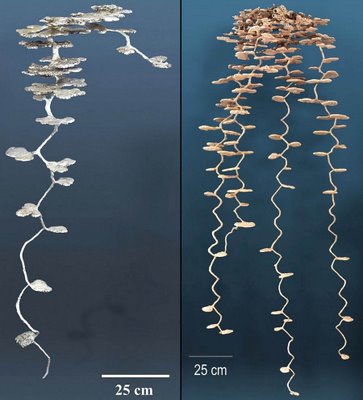

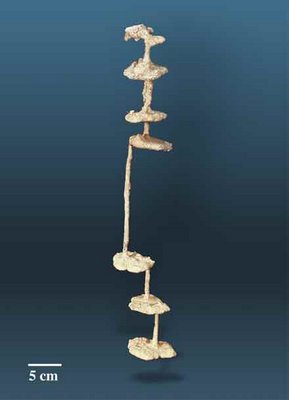

Nest-casting

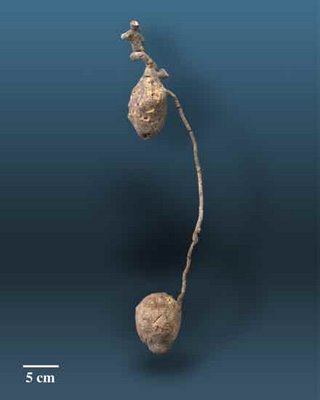

In the Fall of 2001, Cabinet Magazine introduced us to Walter Tschinkel, a professor of entomology at Florida State University. Tschinkel “has been making plaster casts of ant nests since 1982, when he first heard of the strength of orthodontic plaster. The painstaking process involves pouring the plaster down the opening as quickly as it will go in. After the plaster hardens, the excavation begins, but the nest must be taken out piece by piece. (One harvester ant nest, for example, took some five gallons of plaster and came out in 180 pieces.)”

“Sometimes more than ten feet tall, the nests are as beautiful in structure as they are complex.”

In a fascinating research paper (available through Florida State University as a PDF), Tschinkel describes subterranean ants’ nests as “shaped voids in a soil matrix.” These casts, Tschinkel tells us, offer “an invaluable way to visualize ant colonies as they are, that is as a three-dimensional network of tunnels and chambers.”

In an even more interesting – not to mention better illustrated – paper (also available as a PDF) Tschinkel takes us on a verbal tour of this buried architecture: “In contrast to shafts,” he writes, the chambers all “had more or less horizontal floors and a horizontal outline ranging from near circular when small, to multi-lobed when large. In vertical cross-section, they were flattened or slightly domed, with the horizontal dimension much greater than the vertical. All chambers were about 1 cm high, floor to ceiling, no matter what the floor area. Shafts usually intersected chambers at an edge, and connected sequential chambers. Below about 15 to 20 cm, chambers always began as lateral, horizontal-floored extensions from the outside of a spirally-descending shaft that therefore intersected the inner edge of the chamber at an angle ranging from 25º to about 70º.”

The social behavior of the ants is, in many ways, what produces the structures. Tschinkel refers to “movement zones,” in which “partially overlapping sequences from the center of the nest to the periphery” are traced and retraced by individual ants. These movements gradually erode at the walls, expanding surfaces into actual rooms. These “spaces,” then, are really the physical results of social activity, in which a surface becomes a route becomes a chamber – and further branchings spread outward (or downward) from there. (Substantially more information on this – including the influential role of carbon dioxide – can be found in this PDF).

“Chamber morphology,” meanwhile, “was rarely elongated and shaft-like.” Rather, each chamber “began as a niche in the outer wall of a shaft.” Etc. etc.

The process of making these casts almost always kills the ants in the nests, however; but that is “not something I like doing,” Tschinkel says.

Of course, the urge toward revealing invisible architecture can overwhelm even the best…

(Thanks to jpb for the link! And this post is directly related to an earlier post, Wormholes in Wood, which discusses the more conceptual aspects of such a project).

Air Wonder Stories

This 1929 cover from an American speculative fiction magazine inspired Janey Cook to rebuild that fantastic sky city using Lego.

[Images: New air city by Janey Cook; photographs by Calum Tsang and Allan Bedford. Air Wonder Stories cover from Frank R. Paul’s online gallery of sci-fi cover art. More covers coming up soon, in fact, because most of them are completely ridiculous – though architectural. Meanwhile, see the Lego Escher at gravestmor and, of course, The Brick Testament].

(Thanks to Peter Hoh for the link!)

Wormholes in Wood

Emilio Grifalconi, a character in Georges Perec’s 1978 novel Life: A User’s Manual, at one point discovers “the remains of a table. Its oval top, wonderfully inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was exceptionally well preserved; but its base, a massive, spindle-shaped column of grained wood, turned out to be completely worm-eaten. The worms had done their work in covert, subterranean fashion, creating innumerable ducts and microscopic channels now filled with pulverized wood. No sign of this insidious labor showed on the surface.”

Grifalconi soon realizes that “the only way of preserving the original base – hollowed out as it was, it could no longer suport the weight of the top – was to reinforce it from within; so once he had completely emptied the canals of the their wood dust by suction, he set about injecting them with an almost liquid mixture of lead, alum and asbestos fiber. The operation was successful; but it quickly became apparent that, even thus strengthened, the base was too weak” – and the table would have to be discarded.

In preparing to get rid of the table, however, Grifalconi stumbles upon the idea of “dissolving what was left of the original wood” that still formed the table’s base. This would “disclose the fabulous arborescence within, this exact record of the worms’ life inside the wooden mass: a static, mineral accumulation of all the movements that had constituted their blind existence, their undeviating single-mindedness, their obstinate itineraries; the faithful materialization of all they had eaten and digested as they forced from their dense surroundings the invisible elements needed for their survival, the explicit, visible, immeasurably disturbing image of the endless progressions that had reduced the hardest of woods to an impalpable network of crumbling galleries.”

And if we could sculpt and harden our own paths through cities – across continents – what wormholes of structure and space might we find?

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Wormholes).

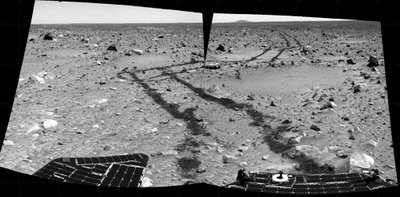

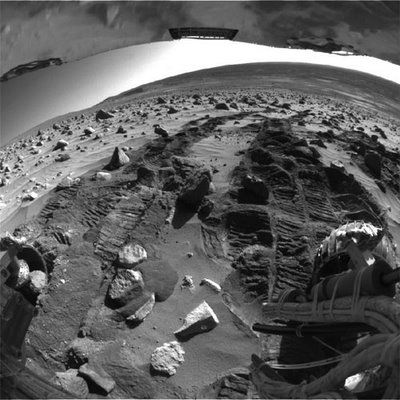

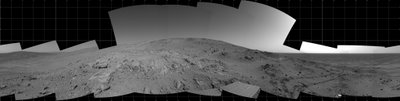

A Mars Supreme

[Images: As if Kazimir Malevich had been reincarnated on Mars to take panoramic geological photography – a new Suprematism of alien terrain – these images are all strangely framed black and white shots like filmstills, taken by NASA’s Spirit rover; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

(Earlier: Mars Rover: A New Film by BLDGBLOG).

The total horizon

These are all photographs of Tokyo taken by Shintaro Sato (©) – click on images for original, and much bigger, versions. This one is particularly great.

(Via the graphic wizards at Coudal Partners).

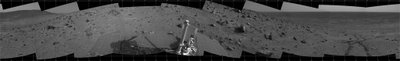

Autistic Canyons, Icebergs of War, and Architecture Made From Light

Much has been made over the past ten days of Stephen Wiltshire, an autistic artist based in London. Given an aerial tour of Rome, for instance, Wiltshire soon reproduced the whole city, in astonishing detail, down to the correct number of arches on the Coloseum – drawing the sketch from memory.

Extraordinary though his sketches may be – I like London’s Albert Hall, personally, though Wiltshire’s oil painting of Los Angeles traffic is also pretty cool – what really got me thinking were the implications this might have for other art forms.

Construction, for instance.

What would happen if you flew a group of autistic miners and bulldozer drivers over the Grand Canyon for several hours? Maybe you even go back the next day, fly circles over certain formations, bank the wings. Memorize fault geometry, strike and dip, the Vishnu schist. Your passengers stare out the window and think. They don’t touch their peanuts. They wear seatbelts.

The whole Grand Canyon, up every tributary and side-fractal’d edge, eroded half-canyons of loose pebbles tumbling under footsteps; fissures, gaps.

You then unleash everyone on the plains of central Asia with a fleet of picks and bulldozers: could they exactly reproduce the Grand Canyon? I think they could. I think Stephen Wiltshire could. Give him a jackhammer and come back in two years.

Such questions have been posed on BLDGBLOG before, of course, but couldn’t that negative earthwork, that unzipped void, be copied exactly to scale? How long would it take? How precise would it be?

Milling new autistic canyons into the surface of the planet.

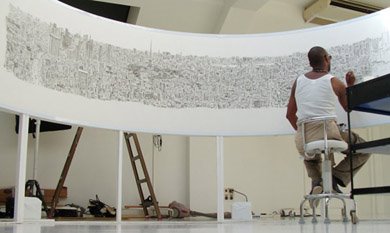

Meanwhile, the Kircher Society, who introduced us to Stephen Wiltshire, also informed us this week that a “massive floating island 2,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 40 feet thick” was almost built by the British military during WWII. Called Pykrete, the material it would have been made from was an “almost indestructible mixture of ice and wood pulp” – though it’s elsewhere been described as “a compound [made] out of paper pulp and sea water which was almost as strong as concrete” (not quite indestructible, then).

Either way, Pykcrete (also spelled “Pykecrete”) would have been used in all manner of ocean-borne construction projects, including a ship that “would serve as a sort of glacial aircraft carrier” in times of war.

Pykcrete structures could not only float, they could repel bullets – an accurate description, on both counts, of my uncle…

Finally, New Scientist gives us the low-down on structures made from light.

Resembling some kind of Renaissance magic trick, a metal work surface “covered with lenses, prisms and mirrors” can now be used to create solid structures out of light – but only if you’ve got “polystyrene beads a few hundred nanometres across.”

“With a flick of a switch,” New Scientist explains, a laser “bathes the beads in an invisible web of infrared light and immediately the beads start collecting… First one or two, then perhaps a dozen fall into line. The beads are still jostling, but something much stronger is holding them in place. Other beads cluster around, seemingly reluctant to join the group. But one by one, they take the plunge, somehow forced into the growing array. Eventually the beads form a chessboard array bound together like a crystal.”

This experiment was conducted by Colin Bain, a chemist at England’s Durham University. He has made what’s called “optical matter” – even “optical cement.”

Of course, architectural metaphors are never far off: “In this microscopic construction site,” we read, “light acts as architect, bricklayer and construction worker, turning building blocks, into temples.”

Bain can change the structures he builds simply by changing the polarization of the light; thus, “suddenly the hexagonal array flips into a square one.” Wavelength, frequency, structure.

Meanwhile, optical researchers Jean-Marc Fournier and Tomasz Grzegorczyk “have big ambitions for optical matter. They are investigating ways to build a giant mirror made from particles bound together entirely by laser light. Such a mirror could be a boon for future space telescopes.” Specifically, they’d use a laser to “trap” particles, which would then “self-organise into a thin reflecting film that takes the shape of a focusing mirror.”

This mirror would apparently be “self-healing.”

Next up: skyscrapers, emergency tents, hydroelectric dams, whole suburbs – created with a single beam of light…

Several months ago, NPR’s Science Friday aired a show called “Stopping Light” – in which the host, Ira Flatow, interviews an Australian physicist. At one point, as if he hasn’t been paying attention, Flatow mutters the strangely uncomfortable, Muppet-like phrase: “Mmm… An archive.”

Download the MP3 right here.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: A cubic meter of fogged space, and – a personal favorite of mine – A Natural History of Mirrors. And thanks, Leah B., for the tip on Pykrete!)

RE: mapping the planet

[Image: The world mapped according to number of aircraft passengers].

[Image: The world mapped according to number of aircraft passengers].

New Scientist has posted a cool article about the wonderful world of warped cartography, courtesy of Worldmapper, based at the University of Sheffield, UK.

Created by Danny Dorling and Anna Barford, Worldmapper transforms traditional cartographic projections using unexpected statistical guidelines: the world according to machine exports, car imports, working tractors, dairy exports, aircraft departures, children in the workforce, population in 2300 AD—etc. etc.

Their goal is to release 365 different maps throughout the upcoming year.

Some particularly eye-popping examples appear here…

[Image: The world mapped according to number of container ports].

[Image: The world mapped according to number of container ports].

[Image: The world mapped according to refugee origin].

[Image: The world mapped according to refugee origin].

[Image: The world mapped according to net immigration – apparently no one’s moving to India].

[Image: The world mapped according to net immigration – apparently no one’s moving to India].

[Image: The world mapped according to expected human population in 2300 AD].

[Image: The world mapped according to expected human population in 2300 AD].

[Image: This is the world mapped according to toy exports and toy imports, respectively].

More—and more and more—of these maps can be found at Worldmapper.

While you’re at it, check out these beautifully executed globes by Ingo Günther’s World Processor.

The organ bank and the bubble

Simultaneous with David Blaine‘s final moments sealed inside a sphere of water, intravenously fed by tubes on the steps of Manhattan’s Modernist opera house – Blaine’s ball was actually a “ten-foot tank with 1.5-inch-thick insulating acrylic walls, filled with 2,000 gallons of spring water,” surely making Archigram roll in their collective architectural grave –

[Images: From Flickr (via Towleroad) and the Gothamist; meanwhile, a reader emailed a few days ago, describing Blaine’s stunt as “the intersection of performance and sculpture.” “The lens of the bowl,” he continued, “seem to magnify [Blaine], and refract the sun spectacularly” – perhaps making this an astronomical event, as well…].

– I was on the phone with author Jeff VanderMeer, recording an interview for BLDGBLOG about the role of urban space and architecture in science fiction.

At one point we got onto the subject of VanderMeer’s so-called “cadaver cathedral,” featured in Veniss Underground. The cadaver cathedral is not a church, however, but a subterranean organ bank, modeled after England’s York Minster, complete with “a plaque to fallen surgeons.”

[Image: The rose window of York Minster, architectural inspiration for the cadaver cathedral].

Though the interview itself won’t appear on BLDGBLOG for another two or three weeks, I thought I’d plug VanderMeer’s work ahead of time – and introduce you to the building.

Somewhere between Blaine’s aquatic sphere, a scene from The Matrix, and a medical device gone horribly awry, VanderMeer describes the High Gothic organ bank as follows:

“Where the sculptures of saints would have been set into the walls, there were instead bodies laid into clear capsules, the white, white skin glistening in the light – row upon row of bodies in the walls, the proliferation of walls. The columns, which rose and arched in bunches of five or six together, were not true columns, but instead highways for blood and other substances: giant red, green, blue, and clear tubes that coursed through the cathedral like arteries. Above, shot through with track lighting from behind, what at first resembled stained-glass windows showing some abstract scene were revealed as clear glass within which organs had been stored: yellow livers, red hearts, pale arms, white eyeballs, rosaries of nerves disembodied from their host.” Etc.

So check back later for the interview – and, in the meantime, feel free to take a look at VanderMeer’s other work.

Finally, the architectural implications of Blaine’s submerged spherical stunt are surely worth a bit of discussion…

(Earlier: Hyperoxic architecture, where David Blaine also pops up; and thanks to Sam Buggeln for his email a few days back!).

Architectural Criticism

I attended a panel discussion in New York City last night, sponsored by David Haskell’s Forum for Urban Design. The attendees, as you’ll see on the invitation, below, represented a number of hefty publications – meaning the combined critical and journalistic weight of the writers in the room was almost enough to redesign Manhattan…

Ultimately, the conversation was both stimulating and worth the trip – but I came away thinking two or three points still needed to be made. Although some of this did come up afterward, without controversy, whilst talking to David Haskell and the panelists, I do want to expand on and clarify some things.

First, early on, one of the panelists stated: “It’s not our job to say: Gee, the new Home Depot sucks…”

But of course it is!

That’s exactly your role; that’s exactly the built environment as it’s now experienced by the majority of the American public. “Architecture,” for most Americans, means Home Depot – not Mies van der Rohe. You have every right to discuss that architecture. For questions of accessibility, material use, and land policy alone, if you could change the way Home Depots all around the world are designed and constructed, you’d have an impact on built space and the construction industry several orders of magnitude larger than changing just one new high-rise in Manhattan – or San Francisco, or Boston’s Back Bay.

You’d also help people realize that their local Home Depot is an architectural concern, and that everyone has the right to critique – or celebrate – these buildings now popping up on every corner. If critics only choose to write about avant-garde pharmaceutical headquarters in the woods of central New Jersey – citing Le Corbusier – then, of course, architectural criticism will continue to lose its audience. And it is losing its audience: this was unanimously agreed upon by all of last night’s panelists.

Put simply, if everyday users of everyday architecture don’t realize that Home Depot, Best Buy, WalMart, even Tesco, Sainsbury’s, and Waitrose, can be criticized – if people don’t realize that even suburbs and shopping malls and parking garages can be criticized – then you end up with the architectural situation we have today: low-quality, badly situated housing stock, illogically designed and full of uncomfortable amounts of excess closet space.

And no one says a thing.

To use a musical analogy: you can have a thousand and one interesting, inspired, intelligent, widely referring, enthusiastic, even opinion-changing conversations about music with almost anyone – including what that person listens to, why, what soundtracks they own, what “bip-hop” really means, whether or not “post-techno” exists, what they actually want to hear on the radio, should file-sharing be legalized, is Chris Cornell this generation’s Sammy Hagar (answer: yes), etc.

But to infer from that conversation – because nobody mentioned Stravinsky or Bach – that those people are philistines who don’t care about music is absurd. In other words, maybe my cousin can’t cite Deleuze and maybe he has no idea who Fumihiko Maki is, or even Frank Lloyd Wright, but does that mean he doesn’t care about architecture?

As it is, one critic writes for approval by another critic, who writes for another critic, who writes for some editor somewhere, or for the head of a department, and no one wants to step out of line. You want to talk about a videogame, or a Tim Burton film, or castles as described in the books of J.K. Rowling – but nope: it’s all Zaha, all the time.

Meanwhile, subscription rates are plummeting.

[Image: A single issue of The Architectural Review now costs US$22.99].

Further – though this may contradict what I say above – strong and interesting architectural criticism is defined by the way you talk about architecture, not the buildings you choose to talk about.

In other words, fine: you can talk about Fumihiko Maki instead of, say, Half-Life, or Doom, or super-garages, but if you start citing Le Corbusier, or arguing about whether something is truly “parametric,” then you shouldn’t be surprised if anyone who’s not a grad student, studying with one of your friends at Columbia, puts the article down, gets in a car – and drives to the mall, riding that knotwork of self-intersecting crosstown flyovers and neo-Roman car parks that most architecture critics are too busy to consider analyzing.

All along, your non-Adorno-reading former subscriber will be interacting with, experiencing, and probably complaining about architecture – but you’ve missed a perfect chance to join in.

Which brings me to two final points, and I’ll try to be quick:

1) Architectural criticism means writing about architecture, not writing about buildings.

Incredibly, in the midst of the talk last night, one of the panelists mentioned Archigram – almost wistfully – commenting that, despite a lack of built projects, Archigram still managed to dynamize and re-inspire the architectural scene of its era. This was done through ridiculous ideas, cheap graphics, a sense of humor, and enthusiasm. But, wait, what was –? Oh, that panelist must have forgotten, because he immediatetly went back to discussing buildings: not ideas, not enthusiasm, not architecture.

Architecture is not limited to buildings!

Temporary Air Force bases, oil derricks, secret prisons, multi-story car parks, J.G. Ballard novels, Robocop, installation art, China Miéville, Department of Energy waste entombment sites in the mountains of southwest Nevada, Roden Crater, abandoned subway stations, Manhattan valve chambers, helicopter refueling platforms on artificial islands in the South China Sea, emergency space shuttle landing strips, particle accelerators, lunar bases, Antarctic research stations, Cape Canaveral, day-care centers on the fringes of Poughkeepsie, King of Prussia shopping malls, chippies, Fat Burger stands, Ghostbusters, mega-slums, Taco Bell, Salt Lake City multiplexes, Osakan monorail hubs, weather-research masts on the banks of the Yukon, Hadrian’s Wall, Die Hard, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Warren Ellis, Grant Morrison, Akira, Franz Kafka, Gormenghast, San Diego’s exurban archipelago of bad rancho housing, Denver sprawl, James Bond films, even, yes, Home Depot – not every one of those is a building, but they are all related to architecture.

Every item in that list should be considered fair game for truly exciting, dynamic, and intellectually adventurous forms of architectural criticism. (And, obviously, many people already are writing about these things – including some of the panelists from last night. I’m just making a point).

2) Finally: The Archigram of today is not studying with Bernard Tschumi and openly imitating The Manhattan Transcripts. The Archigram of today works for Electronic Arts, has no idea who Walter Gropius is, and offers more insights about the future of urban design, space, and the built environment to more people, in more age groups, in more countries, than any practicing architectural critic will ever do, writing about Toyo Ito.

Videogames are the new architectural broadsides.

Being an architectural critic means writing about architecture – even writing about Le Corbusier and Toyo Ito, sure – but that means writing about architecture in its every manifestation: whether it’s built or not, designed by an architect or not, featured in a videogame or not, found anywhere other than inside a novel or not, whether it’s still intact or not – even whether it’s on planet Earth.

If a critic can get people to realize that the everyday architectural world of garages and malls and bad haunted house novels is worthy of architectural analysis – and that architecture is even exciting to discuss – then maybe the trade journals can get some of their subscribers back. At the very least, it’s worth a try.

Even if that means saying: Gee, the new Home Depot sucks.

A simulated planetary environment in the Utah desert

“HAL 9000, the chatty computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey, has come a step closer to reality,” New Scientist claims.

“A team crewing NASA’s Mars Desert Research Station, a simulated planetary environment in the Utah desert, has been experimenting this week with software that can talk to the crew about the status of their spacecraft’s systems.”

“Using wireless headsets,” the article continues, “crew members ask the computer questions such as Is the generator providing power to the batteries? The computer then interrogates sensors embedded in the spacecraft systems, and provides the answer in spoken form. In this week’s trials, the software dealt with simulations of a malfunctioning power system.”

Next week: the crew battles inadequate refrigeration of their much-needed beer: Computer, are you providing enough refrigeration for our beer?

Soon NASA faces papal excommunication as their computer undergoes theological breakdown – it doesn’t believe it was programmed at all…

Raising the question: is Artificially Intelligent architecture a form of religious heresy?

(Images courtesy of NASA. See also Mars Rover: A New Film by BLDGBLOG, Mars and its stunt double and the very, very old ‘Instant City’ on Mars).