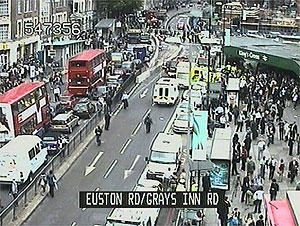

And so now New York City may attempt to install the total cinematic dream that has consumed London’s private security firms for the past three decades, lost as they are in the Warholian ecstasy of filming every last centimeter of urban space, week after month after year, in what is surely the largest outright expenditure of cinematic ambition since… perhaps since film began. That dream is known as the ‘ring of steel’ – part of what I call ‘military urbanism,’ and what is referred to by Eric Lupton, in The New York Times, as ‘fortress urbanism.’

‘For more than a century now,’ we read, ‘winged dragons flanking a shield have guarded each entrance to the City of London. In recent decades, this coat of arms has been reinforced with an elaborate anti-terrorism apparatus known as the “ring of steel,” consisting of concrete barriers, checkpoints and thousands of video cameras. City planners call the system, set up to defend against bombings by the Irish Republican Army, “fortress urbanism.”‘

It would be interesting to put ‘fortress urbanism’ into the context of utopia/dystopia, were that not 1) immediately obvious, and 2) less interesting than going further, into the realm of a generalized psychovideography of urban space.

When Alison and Peter Smithson write that ‘today our most obvious failure is the lack of comprehensibility… in big cities,’ and that the very ‘aim of urbanism is comprehensibility’, we should perhaps reconsider the proclaimed purpose of public surveillance.

The 24-hour closed-circuit voyeurism we impose upon the voidscape of empty car parks and untraveled motorways all around us is already a response to the directionless sprawl of 21st century space. As such, security cameras are the next phase of an advanced urban sociology, a vanguard attempt at understanding the limits, contents and directions of our cities; these cameras have nothing to do with security – unless, of course, cognitive security is the issue at hand.

But to introduce a new term here, we would find ourselves discussing not *psychogeography* – that outdated fetish of a new crop of uninspired theses, from Princeton to the AA – but *psychovideography*, the videographic psyche of the city. If security firms are the new providers of our urban unconscious, a hundred thousand endless films recording twenty-fours a day, indefinitely, then we should perhaps find that the outdated methodologies of the psychogeographers have hit an impasse. The geo- is now in the video-, as it were, and the -graphy survives just the same. Throw in some 24-hour psycho-, and we begin to see the city through the lens of an unacknowledged avant-garde: a subset of the film industry whose advance front has taken on the guise of security.

The security industry, in this case, finds itself a (presumably unwitting) heir to John Cage. As Cage himself wrote, ‘There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear.’ London’s private security firms could hardly agree more passionately – and that surveillant/cinematic enthusiasm now spreads to New York and Chicago.

J.G. Ballard: ‘He had spent the past days in a nexus of endless highways, a terrain of billboards, car marts and undisclosed destinations.’

Iain Sinclair: ‘The landscape is provisional.’

The response: psychovideography. Endless filming. Install the umbrella of a total cinema and move freely into the next phase of urbanism: fortress urbanism.

‘Security’ is a red herring; we are witnessing instead the triumphal rearing-up of an unconscious cinematic fantasy.

Accordingly, we find ourselves, everyday, living more fully than ever before in the utopia of someone else’s inescapable, fortified film set.

The Department of Homeland Cinematics.