[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

This is incredibly random, and is perhaps indisputable evidence that I have fallen head over heels for mourning doves, but I’ve begun noticing, in the backgrounds of various films and TV shows, when mourning doves can be heard cooing—for example, in the new Doug Liman film, Locked Down, there is at least one scene where you can clearly hear a mourning dove singing in a London street.

Recall those recent acoustic studies of cities during the coronavirus lockdown that showed that, among other things, birds no longer had to struggle to be heard over the relentless noise of cars and industrial activity.

The Locked Down mourning dove was presumably a beneficiary of this larger acoustic change—yet it will never know it’s now an international celebrity! Maybe, if you live in London, you’ve even heard the same bird.

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

On the flipside of this, however, I was watching episode 9 of Amazon’s show Patriot the other night when I noticed the call of a Eurasian collared dove somewhere in the background, cooing in the woods. If the fictional setting of that scene is also where it was filmed, then this means Eurasian collared doves are alive and well in the forests of Wisconsin—an absurdly uninteresting point to raise if not for the fact that those doves are an introduced, invasive species.

It occurred to me, then, that you could potentially track invasive species—birds, insects, plants—by way of their unacknowledged appearance in the backgrounds of international film and TV projects.

Think of the scene in W. G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, where a character freezes a video and zooms in on a woman just barely visible in the background, concluding that he is, in fact, looking at the face of his own long-lost mother—indeed the only image he now has of her, this fleeting appearance in the shadows of a film that was actually about something else entirely.

Now imagine that on the scale of an entire ecosystem: a rarely seen bird flashes by behind a character in a blur of color and song, a single tree in a clearing beside two actors, its presence there indicating previously unnoticed changes in soil alkalinity or regional temperatures.

In other words, you could map the spread of invasive species, not to mention the effects of climate change, by noting what creatures pop up, however briefly, in the background of films shot in ecologically transitional regions of the world—an archive of climate effects and landscape futures hiding in plain sight, waiting to be noticed by the right researcher.

[Note: If you’re now desperate to see pictures of mourning doves, I’ve got you covered.]

[Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Collage, Geoff Manaugh, for “

[Image: Collage, Geoff Manaugh, for “ [Image: A geophysical survey of northwestern Arkansas, courtesy

[Image: A geophysical survey of northwestern Arkansas, courtesy  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via

[Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

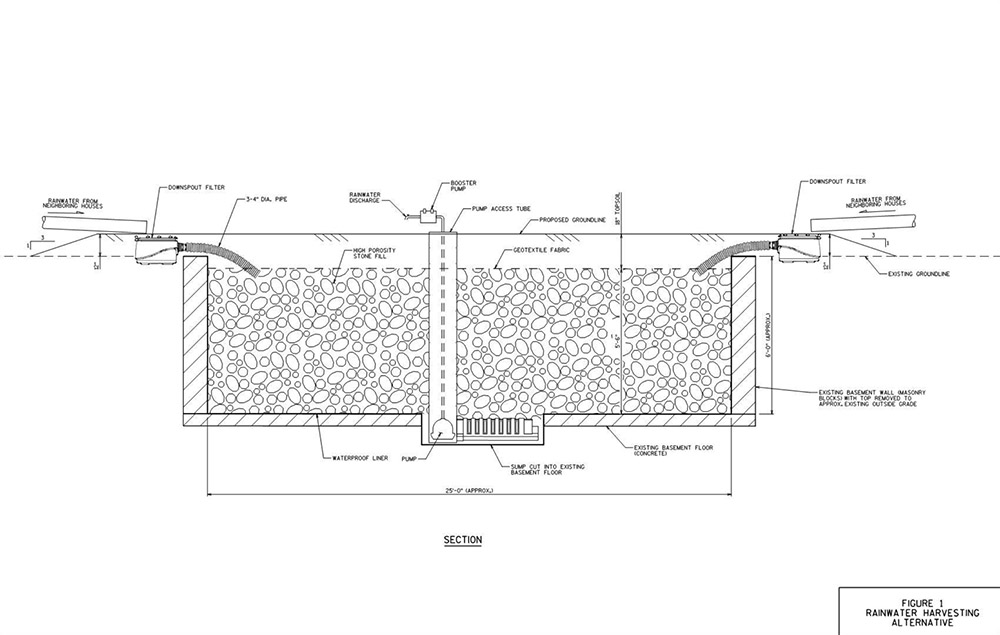

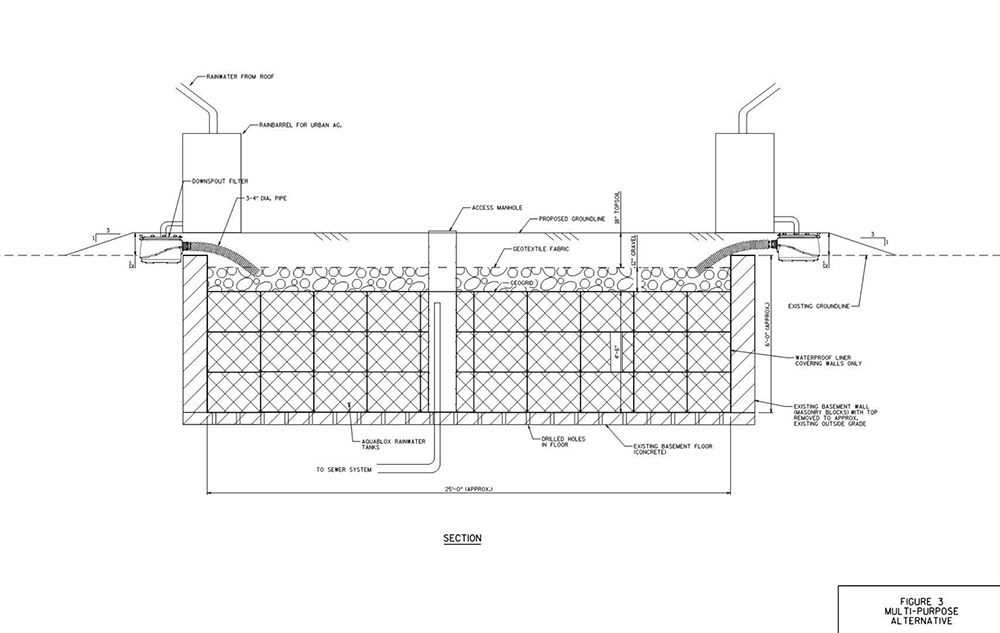

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

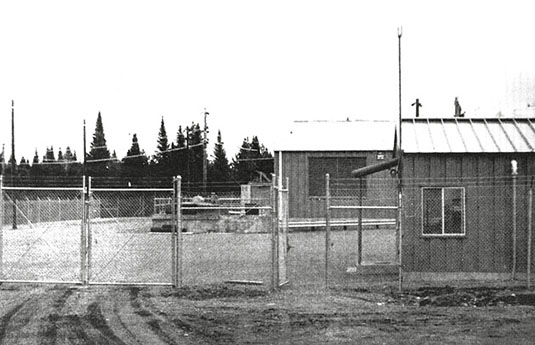

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via

[Image: One of the stations of Project ELF, via  [Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

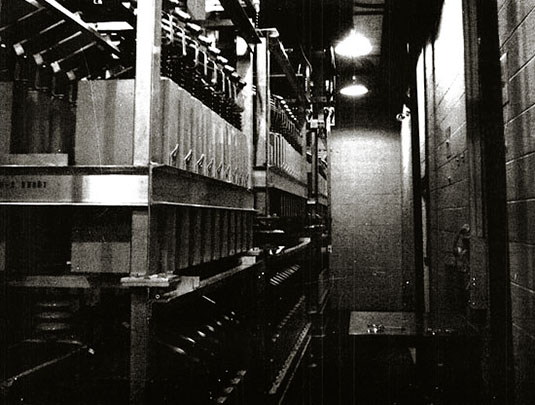

[Image: From Roy Johnson, “Project Sanguine,” originally published in The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)]. [Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].

[Image: Inside Project Sanguine; photo from Roy Johnson, The Wisconsin Engineer (November 1969)].