[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

One of the most interesting sites from a course I taught several years ago at Columbia—Glacier, Island, Storm—was the glacial border between Italy and Switzerland.

The border there is not, in fact, permanently determined, as it actually shifts back and forth according to the height of the glaciers.

This not only means that parts of the landscape there have shifted between nations without ever really going anywhere—a kind of ghost dance of the nation-states—but also that climate change will have a very literal effect on the size and shape of both countries.

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy swisstopo].

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy swisstopo].

This could result in the absurd scenario of Switzerland, for example, using its famed glacier blankets, attempting to preserve glacial mass (and thus sovereign territory), or it might even mean designing and cultivating artificial glaciers as a means of aggressively expanding national territory.

As student Marissa Looby interpreted the brief, there would be small watchtowers constructed in the Alps to act as temporary residential structures for border scientists and their surveying machines, and to function as actual physical marking systems visible for miles in the mountains, somewhere between architectural measuring stick for glacial growth and modular micro-housing.

But the very idea that a form of thermal warfare might break out between two countries—with Switzerland and Italy competitively growing and preserving glaciers under military escort high in the Alps—is a compelling (if not altogether likely) thing to consider. Similarly, the notion that techniques borrowed from landscape and architectural design could be used to actually make countries bigger—eg. through the construction of glacier-maintenance structures, ice-growing farms, or the formatting of the landscape to store seasonal accumulations of snow more effectively—is absolutely fascinating.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

I was thus interested to read about a conceptually similar but otherwise unrelated new project, a small exhibition on display at this year’s Venice Biennale called—in English, somewhat unfortunately—Italian Limes, where “Limes” is actually Latin for limits or borders (not English for a small acidic fruit). Italian Limes explores “the most remote Alpine regions, where Italy’s northern frontier drifts with glaciers.”

In effect, this is simply a project looking at this moving border region in the Alps from the standpoint of Italy.

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

As the project description explains, “Italy is one of the rare continental countries whose entire confines are defined by precise natural borders. Mountain passes, peaks, valleys and promontories have been marked, altered, and colonized by peculiar systems of control that played a fundamental role in the definition of the modern sovereign state.”

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

However, they add, between 2008 and 2009, Italy negotiated “a new definition of the frontiers with Austria, France and Switzerland.”

Due to global warming and and shrinking Alpine glaciers, the watershed—which determines large stretches of the borders between these countries—has shifted consistently. A new concept of movable border has thus been introduced into national legislation, recognizing the volatility of any watershed geography through regular alterations of the physical benchmarks that determine the exact frontier.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

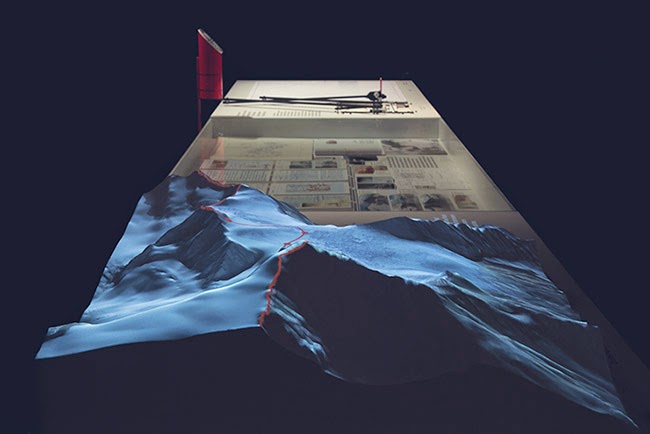

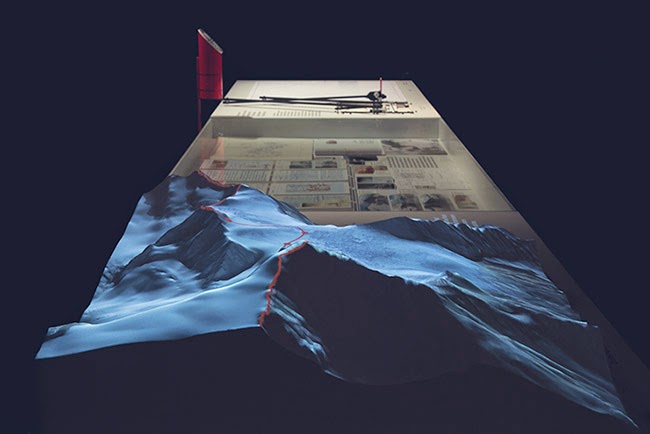

The actual project that resulted from this falls somewhere between landscape surveying and technical invention—and is a pretty awesome example of where territorial management, technological databases, and national archives all intersect:

On May 4th, 2014, the Italian Limes team installed a network of solar-powered GPS units on the surface of the Similaun glacier, following a 1-km-long section of the border between Italy and Austria, in order to monitor the movements of the ice sheet throughout the duration of the exhibition at the Corderie dell’Arsenale. The geographic coordinates collected by the sensors are broadcasted and stored every hour on a remote server via a satellite connection. An automated drawing machine—controlled by an Arduino board and programmed with Processing—has been specifically designed to translated the coordinates received from the sensors into a real-time representation of the shifts in the border. The drawing machine operates automatically and can be activated on request by every visitor, who can collect a customized and unique map of the border between Italy and Austria, produced on the exact moment of his [or her] visit to the exhibition.

The drawing machine, together with the altered maps and images it produces, are thus meant to reveal “how the Alps have been a constant laboratory for technological experimentation, and how the border is a compex system in evolution, whose physical manifestation coincides with the terms of its representation.”

The digital broadcast stations mounted along the border region are not entirely unlike Switzerland’s own topographic markers, over 7,000 “small historical monuments” that mark the edge of the country’s own legal districts, and also comparable to the pillars or obelisks that mark parts of the U.S./Mexico border. Which is not surprising: mapping and measuring border is always a tricky thing, and leaving physical objects behind to mark the route is simply one of the most obvious techniques.

As the next sequence of images shows, these antenna-like sentinels stand alone in the middle of vast ice fields, silently recording the size and shape of a nation.

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Images: From Italian Limes. Photos by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

The project, including topographic models, photographs, and examples of the drawing machine network, will be on display in the Italian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale until November 23, 2014. Check out their website for more.

Meanwhile, the research and writing that went into Glacier, Island, Storm remains both interesting and relevant today, if you’re looking for something to click through. Start here, here, or even here.

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

[Image: From Italian Limes. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani, courtesy of Folder].

Italian Limes is a project by Folder (Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual) with Pietro Leoni (interaction design), Delfino Sisto Legnani (photography), Dawid Górny, Alex Rothera, Angelo Semeraro (projection mapping), Claudia Mainardi, Alessandro Mason (team).

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

[Image: Due to glacial melt, Switzerland has actually grown in size since 1940; courtesy

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

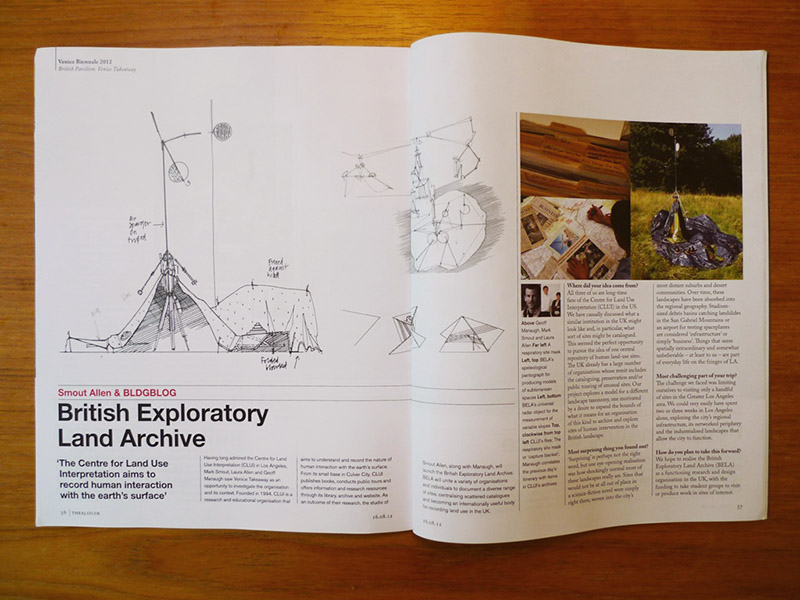

Last week, over at the

Last week, over at the  Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

Although I was unfortunately not able to be in London to attend the opening party, I was absolutely over the moon to get all these photographs, taken by

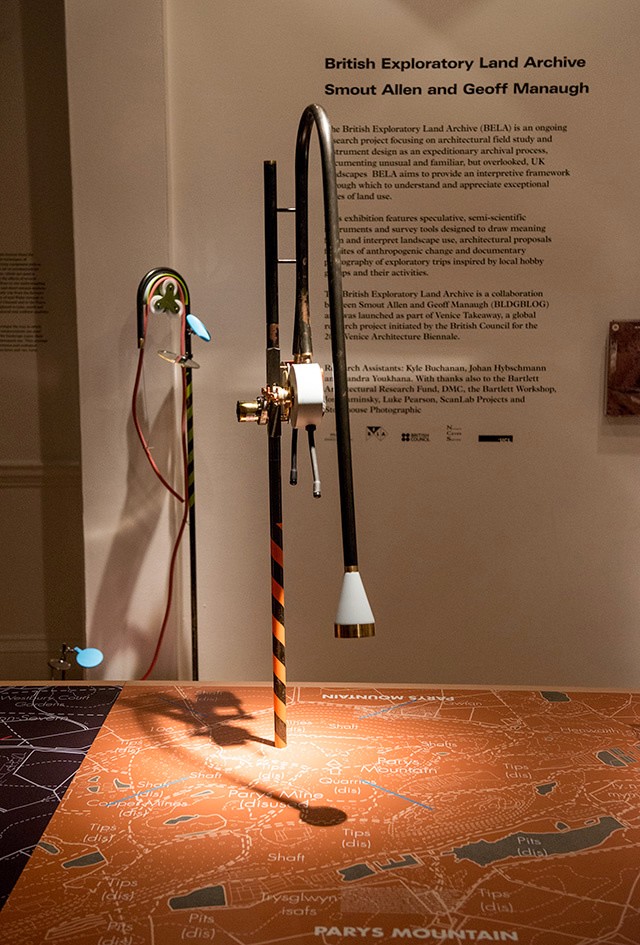

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the

The work on display ranged from cast models of underground sand mines in Nottingham, based on laser-scanning data donated by the  From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

From the bizarre environmental-sensing instruments first seen back at the

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since

I should quickly add that the exhibition is, by far and away, the work of Smout Allen, who burned candles at every end to get this all put together; despite being involved with the project, and working with the ideas all along, since  In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with

In any case, a brief note on the collaboration with  This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This would be an energy-storage landscape—in effect, a giant, island-sized, semi-subterranean field of batteries—where excess electrical power generated by the gargantuan offshore field of wind turbines called the

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

This island of half-buried spinning machines included tiny motor parts and models based on Williams’ own

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.

It was these little parts and models that were 3D-printed in alumide—a mix of nylon and aluminum dust—for us by engineers at Williams.  The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the

The very idea of a 3D-printed energy storage landscape on the British coast, disguised as an island, whirring inside with a garden of flywheels, makes my head spin, and a part of me would actually very much love to pursue feasibility studies to see if such a thing could potentially even be constructed someday: a back-up generator for the entire British electrical grid, saving up power from the  Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

Finally, thanks not only to Williams, but to the

The exhibition is

The exhibition is

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the

[Image: Photo by Mark Smout of a photo by Mark Smout, for the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

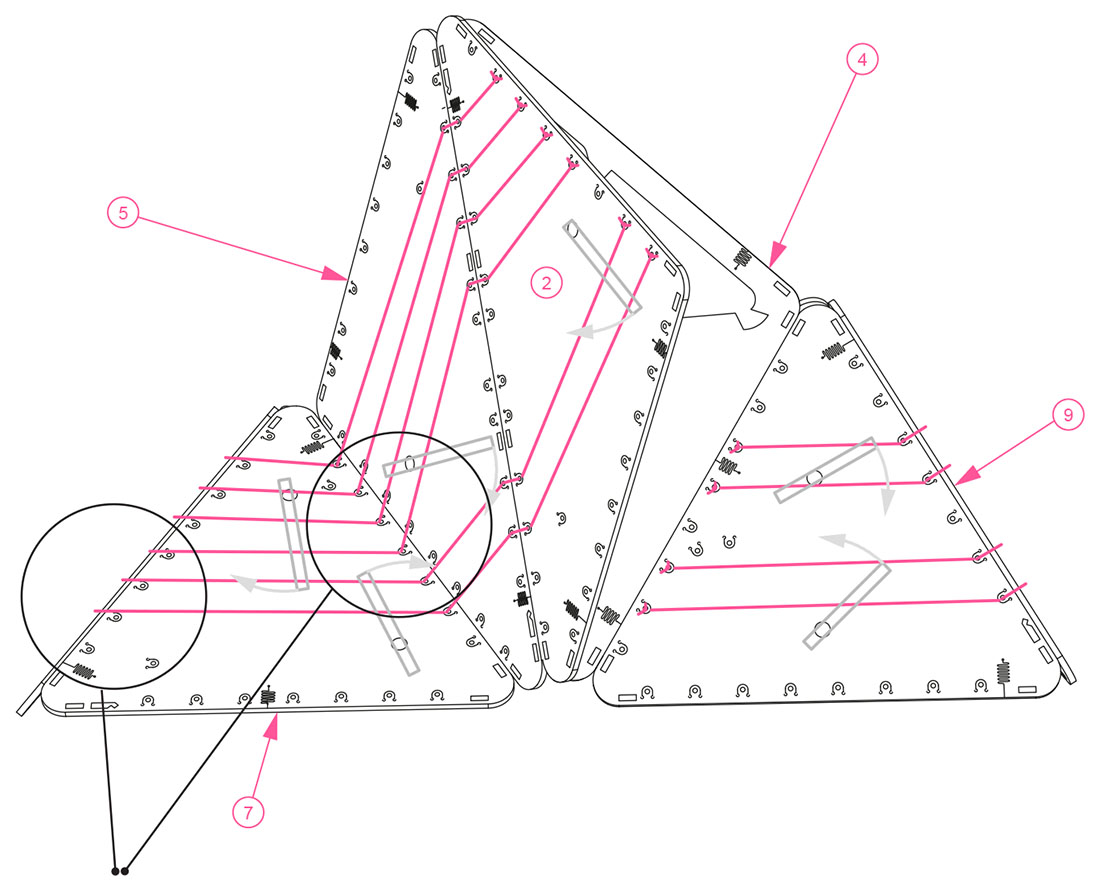

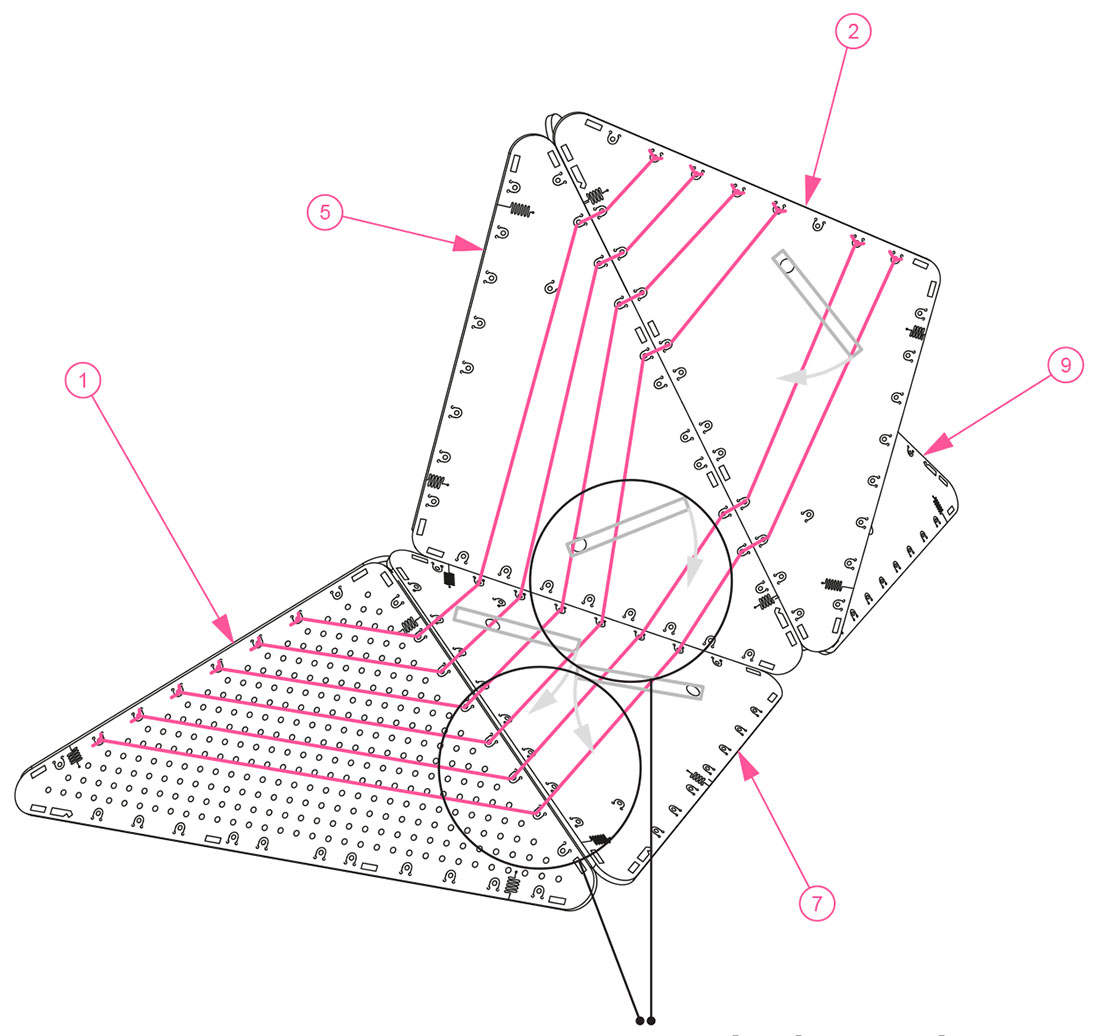

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].