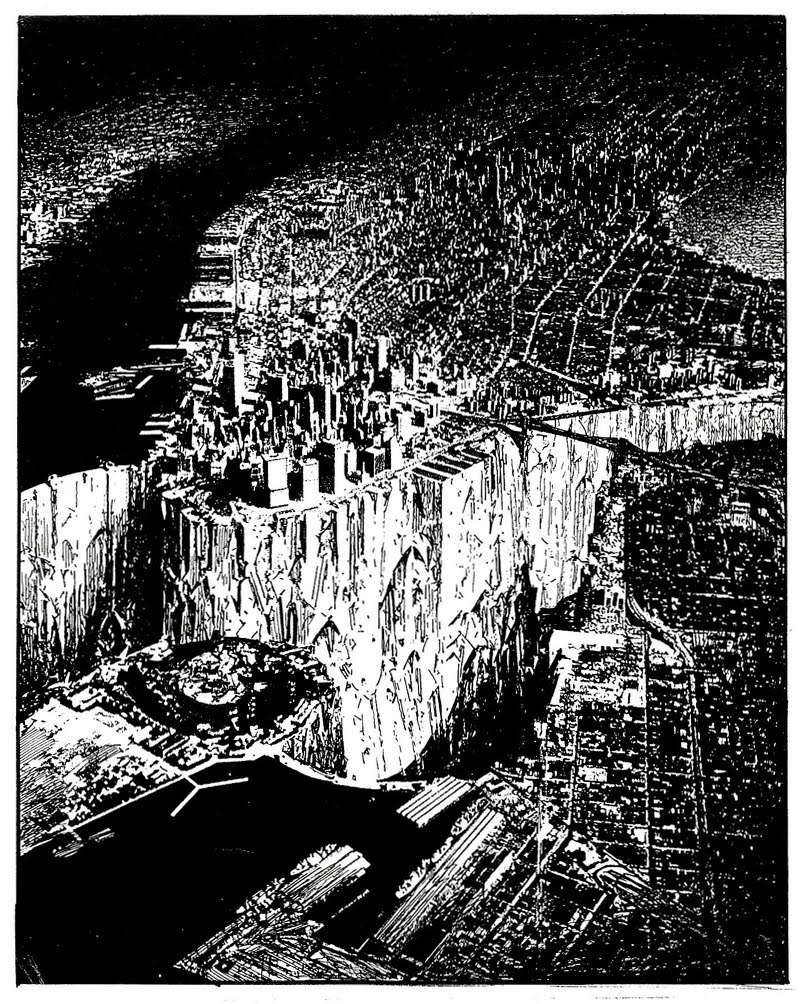

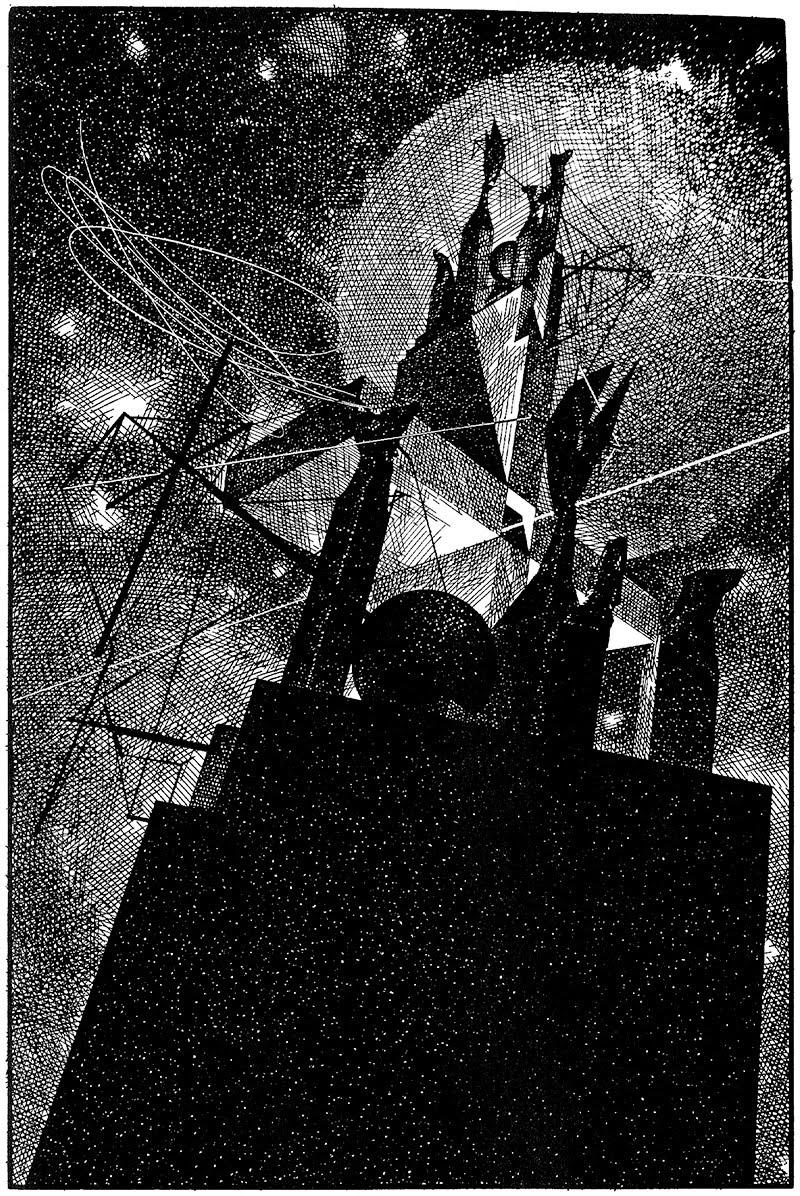

[Image: “Lower Manhattan” (1999) by Lebbeus Woods, discussed extensively here].

[Image: “Lower Manhattan” (1999) by Lebbeus Woods, discussed extensively here].

Like many people, I was—and remain—devastated to have learned that architect Lebbeus Woods passed away last night, just as the hurricane was moving out of New York City and as his very neighborhood, Lower Manhattan, had temporarily become part of the Atlantic seabed, floodwaters pouring into nearby subway tunnels and knocking out power to nearly every building south of 34th Street, an event seemingly predicted, or forewarned, by Lebbeus’s own work.

I can’t pretend to have been a confidant of his, let alone a professional colleague, but Lebbeus’s influence over my own interest in architecture is impossible to exaggerate and his kindness and generosity as a friend to me here in New York City was an emotionally and professionally reassuring thing to receive—to a degree that I am perhaps only now fully realizing. I say this, of course, while referring to someone whose New Year’s toast a few years ago to a room full of friends gathered down at his loft near the Financial District—in an otherwise anonymous building whose only remarkable feature, if I remember correctly, was that huge paintings by Lebbeus himself were hanging in the corridors—was that we should all have, as he phrased it, a “difficult New Year.” That is, we should all look forward to, even seek out or purposefully engineer, a new year filled with the kinds of challenges Lebbeus felt, rightly or not, that we deserved to face, fight, and, in all cases, overcome—the genuine and endless difficulty of pursuing our own ideas and commitments, absurd goals no one else might share or even be interested in.

This was the New Year’s wish of a true friend, in the sense of someone who believes in and trusts your capacity to become what you want to be, and someone who will help to engineer the circumstances under which that transformation might most productively occur.

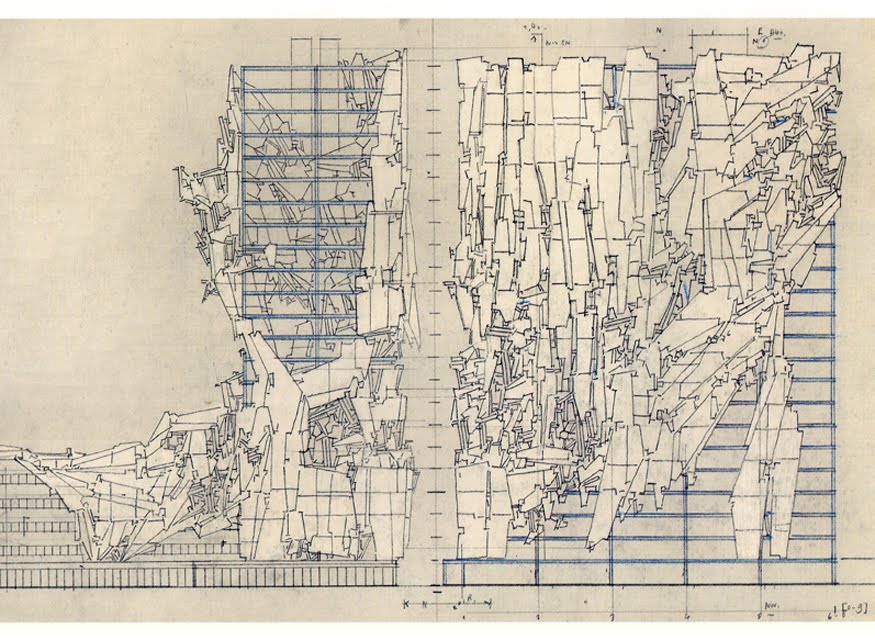

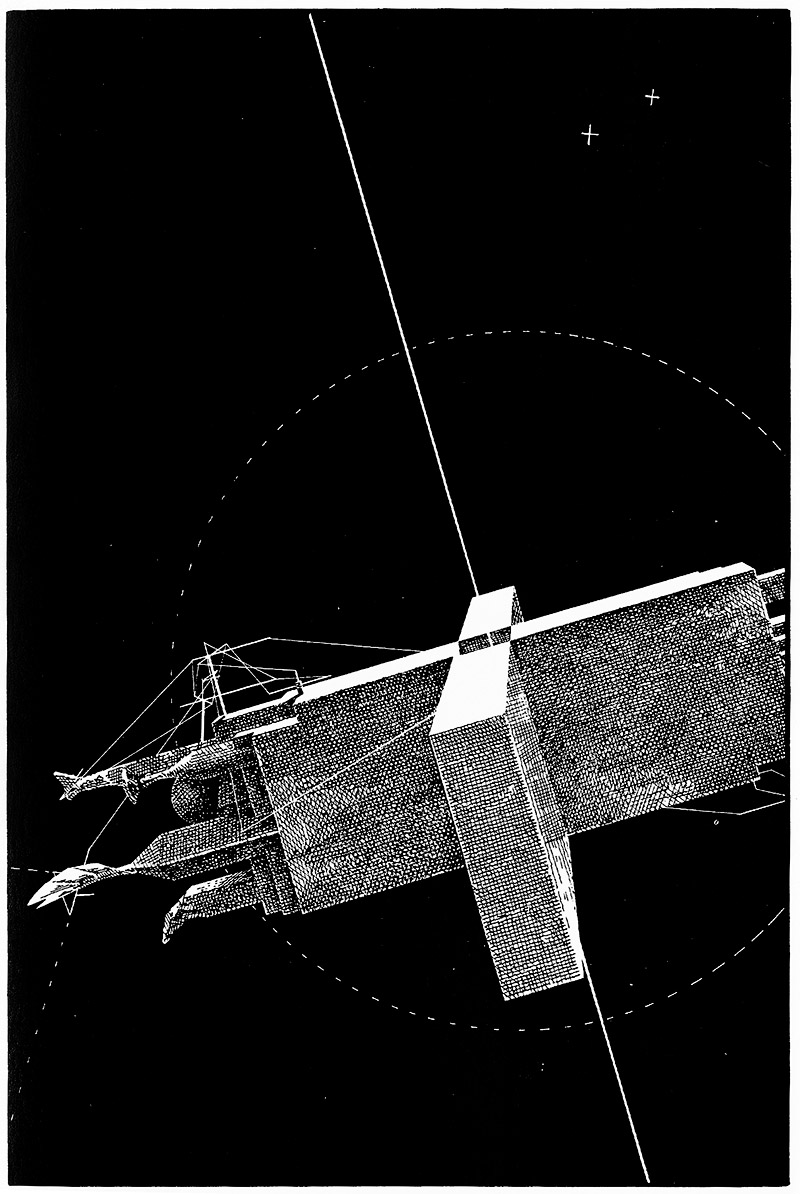

[Images: From War and Architecture by Lebbeus Woods].

[Images: From War and Architecture by Lebbeus Woods].

Lebbeus mentored and taught many, many people, and I am, by every measure, the least qualified of any of them to write about his influence; but learning that Lebbeus has passed away, and under such utterly surreal circumstances, with his own city—literally, the streets all around him—flooding in the darkness as the oceans rose up, compelled me to write something for him, or about him, or because of him, or to him. I have been fortunate enough, or perhaps determined, to live a life where I’ve met several of my heroes in person, and Lebbeus is—he will always be—exactly that, a titanic and strangely omnipresent figure for me whose work set off special effects he himself would be puzzled—even slightly embarrassed—to learn that I’ve attributed to him.

Speaking only for myself, Lebbeus is a canonical figure in the West—and I mean a West not of landed aristocrats, armies, and regal blood-lines but of travelers, heretics, outsiders, peripheral exploratory figures whose missives and maps from the edges of things always chip away at the doomed fortifications of the people who thought the world not only was ownable, but that it was theirs. Lebbeus Woods is the West. William S. Burroughs is the West. Giordano Bruno is the West. Audre Lorde is the West. William Blake is the West. For that matter, Albert Einstein, as Leb would probably agree, having designed an interstellar tomb for the man, is the West. Lebbeus Woods should be on the same sorts of lists as James Joyce or John Cage, a person as culturally relevant as he was scientifically suggestive, seething with ideas applicable to nearly every discipline.

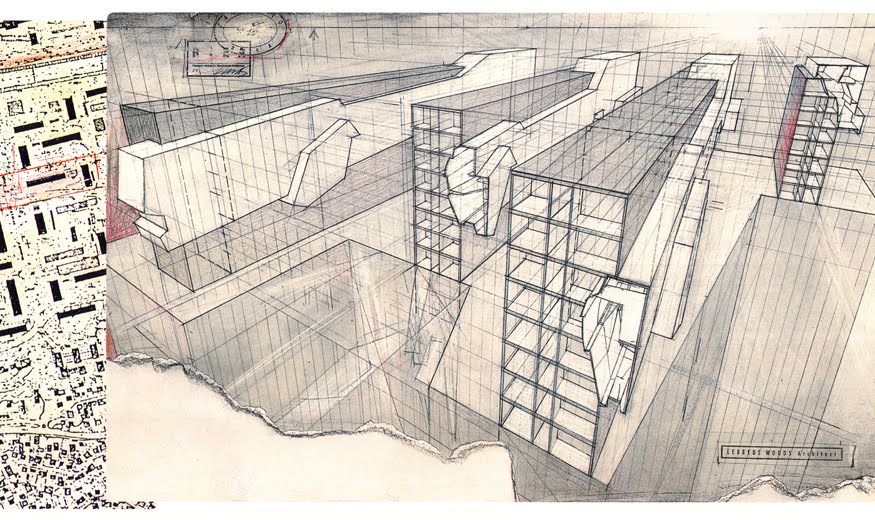

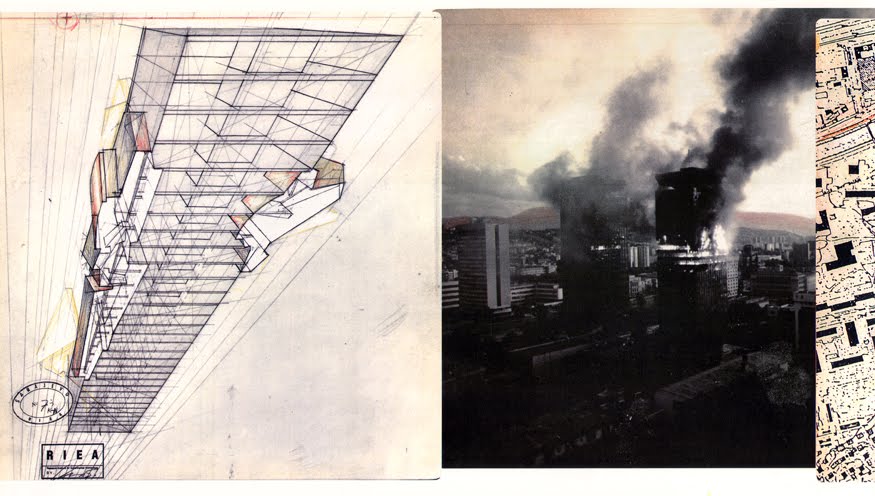

[Images: From War and Architecture by Lebbeus Woods].

[Images: From War and Architecture by Lebbeus Woods].

In any case, it isn’t just the quality of Lebbeus’s work—the incredible drawings, the elaborate models—or even the engaged intensity of his political writings, on architecture as politics pursued by other means or architecture as war, that will guarantee him a lasting, multi-disciplinary influence for generations to come. There is something much more interesting and fundamental to his work that has always attracted me, and it verges on mythology. It verges on theology, in fact.

Here, if I can be permitted a long aside, it all comes down to ground conditions—to the interruption, even the complete disappearance, of the ground plane, of firm terrestrial reference, of terra firma, of the Earth, of the very planet we think we stand on. Whether presented under the guise of the earthquake or of warfare or even of General Relativity, Lebbeus’s work was constantly erasing the very surfaces we stood on—or, perhaps more accurately, he was always revealing that those dependable footholds we thought we had were never there to begin with. That we inhabit mobile terrain, a universe free of fixed points, devoid of gravity or centrality or even the ability to be trusted.

It is a world that can only be a World—that can only, and however temporarily, be internally coherent and hospitable—insofar as we construct something in it, something physical, linguistic, poetic, symbolic, resonant. Architectural.

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

Architecture, for Lebbeus, was a kind of counter-balance, a—I’m going to use the word—religious accounting for this lack of center elsewhere, this lack of world. It was a kind of factoring of the zero, to throw out a meaningless phrase: it was the realization that there is nothing on offer for us here, the realization that the instant we trust something it will be shaken loose in great convulsions of seismicity, that cities will fall—to war or to hurricanes—that subways will flood, that entire continents will be unmoored, split in two, terribly and irreversibly, as something maddeningly and wildly, in every possible sense outside of human knowledge, something older and immeasurable, violently shudders and wakes up, leaps again into the foreground and throws us from its back in order to walk on impatiently and destructively without us.

Something ancient and out of view will rapidly come back into focus and destroy all the cameras we use to film it. This is the premise of Lebbeus’s earthquake, Lebbeus’s terrestrial event outside measured comprehensibility, Lebbeus’s state of war.

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

Because what I like about Lebbeus’s work is its nearly insane honesty, its straight-ahead declaration that nothing—genuinely and absolutely nothing—is here to welcome us or accept us or say yes to us. That there is no solid or lasting ground to build anything on, let alone anything out there other than ourselves expecting us to build it.

Architecture is thus an act—a delirious and amazing act—of construction for no reason at all in the literal sense that architecture is outside rational calculation. That is, architecture—capital-A architecture, sure—must be seen, in this context, as something more than just supplying housing or emergency shelter; architecture becomes a nearly astronomical gesture, in the sense that architecture literally augments the planetary surface. Architecture increases (or decreases) a planet’s base habitability. It adds something new to—or, rather, it complexifies—the mass and volume of the universe. It even adds time: B is separated from C by nothing, until you add a series of obstacles, lengthening the distance between them. That series of obstacles—that elongated and previously non-existent sequence of space-time—is architecture.

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

As Lebbeus himself once wrote, it is through architecture that humans realize new forms of spatial experience that would have been impossible under natural conditions—not in caves, not in forests, not even while out wandering through fog banks or deserts or into the frigid and monotonous vacuity of the Antarctic. Perhaps not even on the Earth. Architecture is a different kind of space altogether, offered, we could say, as a kind of post-terrestrial resistance against unstable ground, against the lack of a trustworthy planet. Against the lack of an inhabitable world.

Architecture, if you will, is a Wile E. Coyote moment where you look down and realize the universe is missing—that you are standing on empty air—so you construct for yourself a structure or space in which you might somehow attempt survival. Architecture is more than buildings. It is a spacesuit. It is a counter-planet—or maybe it is the only planet, always and ever a terraforming of this alien location we call the Earth.

In any case, it’s the disappearance of the ground plane—and the complicated spatial hand-waving we engage in to make that disappearance make sense—that is so interesting to me in Lebbeus’s work. When I say that Lebbeus Woods and James Joyce and William Blake and so on all belong on the same list, I mean it: because architecture is poetry is literature is myth. That is, it is equal to them and it is one of them. It is a way of explaining the human condition—whatever that is—spatially, not through stanzas or through novels or through song.

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

If you were to walk through an architecture school today—and I don’t recommend it—you’d think that the height of invention was to make your building look like a Venus flytrap, or that mathematically efficient triangular spaceframes were the answer to everything, every problem of space and habitability. But this is like someone really good at choosing fonts in Microsoft Word. It doesn’t matter what you can do, formally, to the words in your document if those words don’t actually say anything.

Lebbeus will probably be missed for his formal inventiveness: buildings on stilts, massive seawalls, rotatable buildings that look like snowflakes. Deformed coasts anti-seismically jeweled with buildings. Tombs for Einstein falling through space.

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

But this would be to miss the motivating absence at the heart of all those explorations, which is that we don’t yet know what the world is, what the Earth is—whether or not there even is a world or an Earth or a universe at all—and architecture is one of the arts of discovering an answer to this. Or inventing an answer to this, even flat-out fabricating an answer to this, meaning that architecture is more mythology than science. But there’s nothing wrong with that. There is, in fact, everything right with that: it is exactly why architecture will always be more heroic even than constructing buildings resistant to catastrophic rearrangements of the earth, or throwing colossal spans across canyons and mountain gorges, or turning a hostile landscape into someone’s home.

Architecture is about the lack of stability and how to address it. Architecture is about the void and how to cross it. Architecture is about inhospitability and how to live within it.

Lebbeus Woods would have had it no other way, and—as students, writers, poets, novelists, filmmakers, or mere thinkers—neither should we.

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: Australia’s

[Image: Australia’s  [Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;  [Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via  [Image: Saxophone valve diagram by

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: J.M. Gandy, speculations toward the ruins of John Soane’s Bank of England – but, again, how about speculations toward the Bank of England’s fossils…?]

[Image: J.M. Gandy, speculations toward the ruins of John Soane’s Bank of England – but, again, how about speculations toward the Bank of England’s fossils…?]