The London Fortean Society, of all people, will be hosting a talk called “Secret Tunnels of England: Folklore and Fact” by Antony Clayton, author of the fascinating book Subterranean City: Beneath the Streets of London, on March 9. “So-called secret tunnels are a subject of perennial interest,” we read. “Are there really labyrinths of hidden passageways under our ancient buildings, towns and cities, or are these tunnel tales another seam of England’s rich folklore?” See, for example, BLDGBLOG’s earlier look at the Peterborough tunnels. There is still time to get on a waiting list for tickets. For what it’s worth, I also referred to Clayton’s book in my recent essay for The Daily Beast about the Hatton Garden heist. (Event originally spotted via @urbigenous).

Tag: Folklore

The Peterborough Tunnels

A weird old story I came across in my bookmarks this morning tells a tale of tunnels under the town of Peterborough, England.

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of Peterborough Today].

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of Peterborough Today].

The local newspaper, Peterborough Today, refers to a woman described simply as “a grandmother” who claims “that she crawled through a tunnel under Peterborough Cathedral as a schoolgirl.” That experience—organized as a school trip, of all things—was “terrifying”; in fact, it was “so scary that it gave her nightmares for weeks afterwards.”

About 25 of us went down into the tunnel, one at a time; none of the teachers came in. It was pitch black, had a stone floor and was about two feet high and three feet wide. We crawled along on our hands on knees. The girl in front of me stopped and started screaming, she was so scared. The tunnel started in the Cathedral and ended there too; we were down there for what seemed like ages. When I eventually got home I was in tears. Afterwards I had horrible nightmares for weeks about being buried alive underneath the Cathedral.

What’s fascinating about the story, though, is the fact that not everyone even agrees that these tunnels exist. A “city historian” quoted in the same article says that, while “there are small tunnels under the Cathedral,” they are most likely not tunnels at all, but simply “the ruins of foundations from earlier churches on the site, dating from Saxon times.” The girls would thus have been crawling around amongst the foundations of ruined churches, lost buildings that long predated the cathedral above them.

But local legends insist that the tunnels—or, perhaps, just one very large tunnel—might, in fact, be real. To this end, an amateur archaeologist named Jay Beecher, who works in a local bank by day, has “been intrigued by the legend of the tunnel ever since he was a young boy when he was regaled with tales that had been passed down the generations of a mysterious passageway under the city.” This “mysterious passageway under the city” would be nearly 800 years old, by his reckoning, and more than a mile in length. “Medieval monks may have used the tunnel as a safe route to visit a sacred spring at Holywell to bathe in its healing waters,” we read.

Although Beecher has found indications of the tunnel on city maps, not everyone is convinced, claiming the whole thing is just “folklore.” But it is oddly ubiquitous folklore. One former resident of town who contacted the newspaper “claimed that a series of tunnels ran between Peterborough and Thorney via a secret underground chapel.” Another “said that he recalled seeing part of a tunnel in the cellar at a home in Norfolk Street, Peterborough,” as if the tunnel flashes in and out of existence around town, from basement to basement, church cellar to pub storage room, more a portal or instance gate than an actual part of the built environment. And then, of course, there is the surreal childhood memory—or nightmare—recounted by the “grandmother” quoted above who once crawled beneath the town church with 25 of her schoolmates, worried that they’d all be buried alive in the center of town (surely the narrative premise of a childhood anxiety dream if there ever was one).

No word yet if Beecher has found his archaeological evidence, but the fact that this particular spatial feature makes an appearance in the dreams, memories, or confused geographic fantasies of the people who live there—as if their town can only be complete given this subterranean underside, a buried twin lost beneath churches—is in and of itself remarkable.

(If this interests you—or even if it doesn’t—take a quick look at BLDGBLOG’s tour through the tunnels and sand mines of Nottingham, or stop by this older post on the “undiscovered bedrooms of Manhattan“).

Books Received

[Image: A riverboat library in Bangladesh; image courtesy of the Gates Foundation].

[Image: A riverboat library in Bangladesh; image courtesy of the Gates Foundation].

Many, many books have arrived at the home office here, and I’m thus once again woefully behind in tallying up all the titles that have come my way. Accordingly, there are still many more write-ups to come, but it will be next month, after some upcoming travels, before I get to those other books.

Meanwhile, as has always been the case with Books Received posts, I have not read all of the books linked here and not all of them are necessarily new. However, in all cases, these are included for the interest of their approach or subject matter, and the following list should easily give just about anyone at least one good book to read over the coming summer.

1) City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age by P.D. Smith (Bloomsbury) — P.D. Smith’s voluminous look at the history of urbanism stretches from the Sumerians to the 2012 London Olympics, from Tenochtitlán to Dubai, from the Code of Hammurabi to J.G. Ballard, and from the Italian Renaissance to the urban ruins of nuclear war. Smith has organized his book like a travel guide, albeit not for a particular metropolis but for the city in and of itself. Chapters are thus divided into overarching categories such as “arrival,” “where to stay,” “getting around,” and more, and while the result can sometimes conflate otherwise quite different urban phenomena found in disparate cities around the world, that slight sense that things are starting to blur is evened out by Smith’s eye for detail in the stories and anecdotes he relates, particularly in the book’s many boxed texts and sidebars. Migration, food security, global tourism, natural disasters, economic expansion, and war: these are all perennial influences on urban form—and urban futures—and Smith works hard to show their role in shaping the life of what he calls “the ape that shapes [its] environment, the city builders.” City comes out in the United States in June 2012.

2) Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet by Andrew Blum (Ecco) — I had the pleasure of receiving periodic email updates from author Andrew Blum as he traveled to the unmarked buildings and coastal warehouses—amongst many other sites—that enable, store, and protect what we broadly refer to as the internet. The resulting book, released earlier this week, tells the story of those travels: it is Blum’s field guide to the physical infrastructure of contemporary data, tracking the internet’s actual geography, the sites where the switches are kept and the servers are cooled, where the cables come out of the sea and relay onward, deeper into cities and suburbs, into office and apartments like the one from which I’m posting this. “The Internet couldn’t just be everywhere,” Blum writes, questioning ethereal metaphors like “the cloud” or the abstract “tubes” of the book’s title. “But then where was it? If I followed the wire, where would it lead? What would that place look like? Why were they there? I decided to visit the Internet.” In one particularly memorable description, Blum quips that he “had begun to notice that the Internet had a smell, an odd but distinctive mix of industrial-strength air conditioners and the ozone released by capacitors,” as if even the most amorphous realms of data have their own peculiar body odor. This body—the “tubes” of the internet—leads Blum from underground London to the middle of nowhere in central Oregon, from downtown Milwaukee to locked rooms in Amsterdam, on the trail of the “pulses of light” that give the internet physical and geographic form.

3) The Appian Way: Ghost Road, Queen of Roads by Robert A. Kaster (University of Chicago Press) — As Kaster’s book claims on its opening page, “No road in Europe has been so heavily traveled, by so many different people, with so many different aims, over so many generations.” The Appian Way, which cuts broadly southeast from the old city walls of Rome, gives Kaster—a Classicist at Princeton—a long and meandering geography on which to base this otherwise concise, almost pamphlet-length look at the Italian landscape and how it has evolved over the past two millennia. From marshes and town centers to incongruously 21st-century wind farms where the ancient road all but disappears into gravel-strewn ruins, by way of endless crumbling tombs that will be familiar to any fan of Piranesi, Kaster’s book describes the sites, monuments, churches, cemeteries, and more that give readers an opportunity to explore the historical—usually archaeological—context for this legendary piece of transportation infrastructure. The Appian Way is part of the “Culture Trails” series from the University of Chicago Press.

4) Ghetto at the Center of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong by Gordon Mathews (University of Chicago Press) — Mathews offers a kind of anthropological critique of globalization in the guise of architectural reportage, telling the story of Chungking Mansions, “a dilapidated seventeen-story commercial and residential structure in the heart of Hong Kong’s tourist district,” and using close descriptions of everyday life in the complex to build a cross-section of the global economy. “A remarkably motley group of people call the building home,” we read in the book’s own description: “Pakistani phone stall operators, Chinese guesthouse workers, Nepalese heroin addicts, Indonesian sex workers, and traders and asylum seekers from all over Asia and Africa live and work there—even backpacking tourists rent rooms. In short, it is possibly the most globalized spot on the planet.”

5) Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect by Robert J. Sampson (University of Chicago Press) — Sampson’s very academic book—less narrative than statistical and analytic, and keenly based in empirical research—weighs the importance of community in defining, empowering, and uniting the city of Chicago, neighborhood by neighborhood.

6) New York at War: Four Centuries of Combat, Fear, and Intrigue in Gotham by Steven H. Jaffe (Basic Books) — Jaffe has written an incredibly interesting military history of New York City, beginning well before it was either New York or a city. Jaffe’s detailed accounts of early colonial battles and Revolutionary battlegrounds reveal the, to me, surprising number and topographic diversity of combat sites that dot the greater New York landscape. In the process, he offers little-known historical anecdotes—for instance, not only that Wall Street is so named after the defensive wall once constructed there, from one side of the island to the other, but that the wall was the first example of debt-financed urban infrastructure in what were then Dutch colonies. Jaffe’s look at a military urbanism peculiar to New York, from the 1600s to WWII to the security bollards of post-9/11 NYC, has proven hard to put down.

7) The Insurgent Barricade by Mark Traugott (University of California Press) — Traugott’s history of the barricade as a uniquely successful “technique of insurrection” is, first and foremost, a look at the spatial politics of the built environment. These politics operate in at least two primary, and clearly oppositional, ways, Traugott suggests. The first is the deliberate mis-use or counter-use of the city, transforming it into something that, through improvisatory re-design, can be express the political demands of an otherwise overlooked constituency. This is the production of barricades, which interfere with and strategically realign the internal movements of the city. The other side of this story, however, is the purposeful and systematic alteration of a city’s fabric precisely so that its everyday spaces cannot be used as outlets for political expression. In the latter example, streets can be widened or public spaces closely surveilled; in the former, makeshift tools and ad hoc materials, from cobblestones to wheelbarrows, can be transformed at a moment’s notice into walls that clog the city’s arteries and bring its streets to a halt. Traugott shows how all this has played out over more than four centuries of European urban history, also looking at what future spatial possibilities exist, on both sides of the barricade, for the political life of the metropolis.

8) Horseshoe Crabs and Velvet Worms: The Story of the Animals and Plants That Time Has Left Behind by Richard Fortey (Alfred A. Knopf) — Fortey is easily one of my favorite natural history writers, and his Earth: An Intimate History remains high on my list of recommended books. With this new book, Fortey takes on the question of survival—or super-survival—in creatures whose wildly successful evolutionary paths mean they have had a disproportionately deep effect on whole ecosystems still thriving today. This is “life’s history told not through the fossil record but through the stories of organisms that have survived, almost unchanged, throughout time,” in the book’s own words. The horseshoe crabs and velvet worms of the title are only two of the most-cited creatures in Fortey’s unsurprisingly enjoyable book.

9) The Prehistory of Home by Jerry D. Moore (University of California Press) — Moore starts things off with the unfortunate claim that “various animals build shelters, but only humans build homes,” an unprovable statement that belongs on the sadly endless pile of false comparisons made about humans and animals. Indeed, only four pages later, Moore himself writes that “we [humans] have been building homes longer than we have been Homo sapiens,” which can literally only be true if animals—that is, non-humans or non-Homo sapiens—can, after all, build homes, not just shelters, and have been doing so all along. In any case, this minor but by no means inconsequential quibble shouldn’t hold you back from enjoying Moore’s engaging history of the home—that is, the symbolically rich personal shelter—which he takes on a wide and exciting run from hand-woven walls and mud floors on the coast of Peru all the way to maximum security prisons, from Mesopotamian walled cities to gated suburbs, and from bachelor pads to underground “dwellings” built for the recently deceased in globally diverse burial practices. Part archaeological survey dating back, as Moore explains, to before humans were Human, and part speculative treatise as to why humans have an emotional need for homes at all, Moore’s book spans hundreds of thousands of years and nearly every continent.

10) The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic World by Robert McGhee (Oxford University Press) — McGhee, an archaeologist at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, “paints a vivid portrait of Viking farmers, entrepreneurial Inuit, and Western explorers” in their encounter with, and long-term settling of, the Arctic. Though the book has been out for several years, it just crossed my desk and I look forward to jumping in over the summer.

11) Rough-Hewn Land: A Geologic Journey from California to the Rocky Mountains by Keith Heyer Meldahl (University of California Press) — Meldahl’s book is, in its own words, “a 1000-mile-long field trip back through more than 100 million years of deep time to explore America’s most spectacular and scientifically intriguing landscapes.” Those landscapes are the western plateaus, mountains, and deserts of the southwestern United States, a region whose terrain now verges on the over-exposed—hardly a season goes by without a new book on the subject—but, as Meldahl suggests, “geology is stranger than fiction,” and the book he’s built around that statement is a worthwhile read.

12) American Sunshine: Diseases of Darkness and the Quest for Natural Light by Daniel Freund (University of Chicago Press) — Freund’s book is a delightfully idiosyncratic look at the “quest for natural light” in American culture, from the earliest use of tanning beds as a kind of surrogate sun to the mainstream acceptance of “light therapy” as a cure for Seasonal-Affective Disorder, and from the marketing of climate tourism to the development of specialty lighting rigs for use in industrial food preparation. Freund explains in his introduction that the book was motivated by three otherwise unrelated historical figures—Akhenatan, Vitruvius, and Linnaeus—all of whom represent for Freund “the universality of sunlight as a subject for consideration.” The results are this unique look at the confluence of personal health, urban design, and near-religious popular beliefs about the purifying power of sunlight over roughly 150 years of American culture.

13) Sealab: America’s Forgotten Quest to Live and Work on the Ocean Floor by Ben Hellwarth (Simon & Schuster) — Hellwarth relates the surprisingly overlooked story of U.S. Navy “saturation divers” and the international oceanographers whose research helped to pioneer the construction of deepsea equipment and large-scale architectural environments that almost made living on the ocean floor an everyday reality. Equal parts tropical retro-futurism, complete with scenes of Jacques Cousteau assembling his Conshelf habitats in the Mediterranean Sea, and high-tech adventure story populated by military super-athletes and entrepreneurial gear manufacturers few of us even knew existed—including surreal high-pressure diving experiments involving presumably quite bewildered farm animals—Hellwarth’s book tells the true history of what have been (and what might still be) for human inhabitation of the oceans. Best of all, it’s almost entirely set in a quasi-utopian underwater world, like Archigram crossed with The Abyss.

14) American Urban Form: A Representative History by Sam Bass Warner and Andrew H. Whittemore (MIT Press) — Warner and Whittemore have produced an illustrated historical survey of U.S. urbanism, with short chapters ranging from “the city’s seventeenth-century beginnings” on the Atlantic coast to “the federally supported city” of the 1950s, ending with a somewhat obligatory overview of the “global city” and its suburban fringe. The book is a great introduction to the processes that have influenced and restrained urban development in the United States for more than three centuries, but it focuses more on presenting a coherent narrative—often reading more like a special issue of The Economist—as opposed to developing an original or otherwise surprising new interpretation of American urban form.

15) The Chicago River: An Illustrated History and Guide to the River and Its Waterways by David M. Solzman (University of Chicago Press) — Re-released in its current, second edition back in 2006, Solzman’s book will no doubt already be familiar to many readers of BLDGBLOG, but his history of the Chicago River, its ecological context and industrial re-engineering, complete with a hands-on guide for anyone who might want to explore it, was new to me.

16) Pyongyang: Architectural and Cultural Guide edited by Philipp Meuser (DOM Publishers) — In print for less than three months, Meuser’s guide is already something of a cult classic in architectural circles, offering as it does a photographic and textual survey of the gonzo dictatorial postmodernism of Pyongyang, North Korea. A genuinely fascinating look at the political symbology of a capital city—Stefano Boeri’s memorable description of Pyongyang as a “rogue city” comes to mind—this slipcased, two-volume set offers “photographs and descriptions” in one book, including brief lessons on Pyongyang’s overall urban organization, and, in the other, what Meuser calls “background and comments.” These latter categories include—incredibly—excerpts from an architectural pamphlet written by the late Kim Jong-Il, who explains to his readers that, among other things, “architects are creative workers and operations officers,” spatially gifted functionaries of the State. Many of the photographs found in each volume can unfortunately resemble washed-out tourist postcards, and the buildings themselves are often striking for their super-ornamental, propagandistic absurdity—in a city whose natural setting makes it look oddly like Memphis, Tennessee—but to mock the city so easily and dismissively would be to miss the guide’s more interesting insight, which is that Pyongyang is, in fact, a remarkably assembled collection of processional spaces and monumental object-buildings, aesthetically arranged in a kind of 3-dimensional essay extolling the wonders of uncontested state power.

17) How to Make a Japanese House by Catherine Nuijsink (NAi Publishers) — Although architecture blogs have perfected the art of Japanese house fatigue over the past few years—in which it seems like a central server somewhere has been auto-feeding photos of small Japanese houses to the same design blogs over and over again every week—Nuijsink’s book is, refreshingly, a more substantive exploration of 21st-century domestic space in Japan, complete with one-on-one architectural interviews and occasional floor plans. Many of the projects you will already have seen online, but, given the breadth of context here, some great photographs, and three framing “monologues” written by architects Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, Taro Igarashi, and Jun Aoki, it more than justifies its publication.

18) Dash 5: The Urban Enclave edited and produced by Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (NAi Publishers) — Dash—not quite a magazine, more of a subscription book series—continued last autumn with this look at the “urban enclave,” which the editors have framed as an often progressively intended urban mega-project. These developments, both privately and publicly funded, can create what one of the book’s essays calls “a city-within-the-city” or a city “made up of miniature utopias”: social developments and architectural forms that appear, at first glance, to be entirely disconnected from one another but that, the authors argue, actually invigorate the city through these clear and obvious contrasts. The enclave offers—in fact, it does not let you avoid—”the proximity and the accessibility of ‘the other.'” Agree or disagree, it’s another well-produced issue in the ongoing Dash series, including an interesting look at Oswald Mathias Ungers’s notion of Grossform by historian Lara Schrijver, author of Radical Games.

19) Toward A Minor Architecture by Jill Stoner (MIT Press) — Stoner’s book looks to “dissect and dismantle prevalent architectural mythologies,” and to do so through a turn toward fiction—but the result is an often somewhat timid and unnecessarily academic entry in what should be a very rich conversation. Stoner relies too much on citations from the usual suspects found in your, mine, and everyone else’s thesis papers from the 1990s (Deleuze & Guattari, Walter Benjamin, Leibniz, Sigmund Freud, Italo Calvino, and even the now sadly over-exposed J.G. Ballard). But, having said that, it’s hard not to find pleasure in a book that takes, well, J.G. Ballard, Walter Benjamin, Sigmund Freud, Franz Kafka, James Joyce, and more—even the Berlin Wall—as fuel for a descriptive expansion of architecture into various other genres and media.

20) Care of Wooden Floors by Will Wiles (Amazon) — Many of you will recognize Will Wiles from his work as deputy editor of ICON magazine or his excellent though infrequent blog Spillway, but here he turns to fiction in a debut novel that tells the story of a man slowly going mad whilst house-sitting for a friend in Eastern Europe. From the book’s own description: “A British copywriter house-sits at his composer friend Oskar’s ultra-modern apartment in a glum Eastern European city. The instructions are simple: Feed the cats, don’t touch the piano, and make sure nothing damages the priceless wooden floors. Content for the first time in ages, he accidentally spills some wine. The apartment and the narrator’s sanity gradually fall apart in this unusual and satisfying novel.” The book has already been released in the UK, where it’s been receiving good reviews as a dark-humored “disaster novel,” but it’s not due out in the States until later this year, when it will become part of the first crop of books published directly and exclusively by Amazon.com.

21) Blueprints of the Afterlife by Ryan Boudinet (Grove Press) — Boudinet’s “bracingly weird new novel” has been receiving high praise and enviable comparisons for the author’s style, including to such writers as Philip K. Dick, William Burroughs, and Neal Stephenson, as Blueprints of the Afterlife picks up considerable buzz in the scifi/speculative fiction world. Fans of odd settings and spatial details will presumably appreciate the book’s “sentient glacier” or its “full-scale replica of Manhattan under construction in Puget Sound.” I’m looking forward to reading this while traveling over the next few weeks.

22) Joe Golem and the Drowning City by Mike Mignola and Christopher Golden (St. Martin’s Press) — It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan of Mike Mignola’s work, and his novelistic collaborations with Christopher Golden have so far been great, if not quite as gripping as Mignola’s own early Hellboy tales. Joe Golem tells the story of a flooded Manhattan, or, in the book’s own words: “In 1925, earthquakes and a rising sea level left Lower Manhattan submerged under more than thirty feet of water, so that its residents began to call it the Drowning City. Those unwilling to abandon their homes created a new life on streets turned to canals and in buildings whose first three stories were underwater.” The results, set 50 years after the flooding, are somewhere between H.P. Lovecraft and Central European urban folklore, featuring occasional black and white drawings by Mignola.

All Books Received: August 2015, September 2013, December 2012, June 2012, December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”), May 2010, May 2009, and March 2009.

The Migration of Mel and Judith

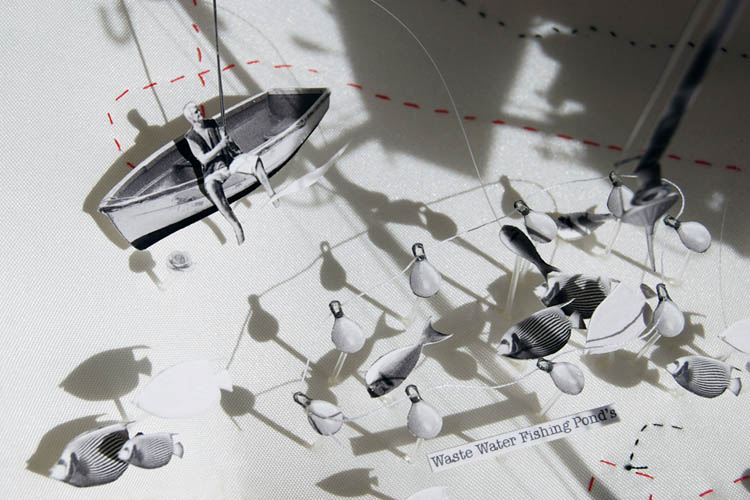

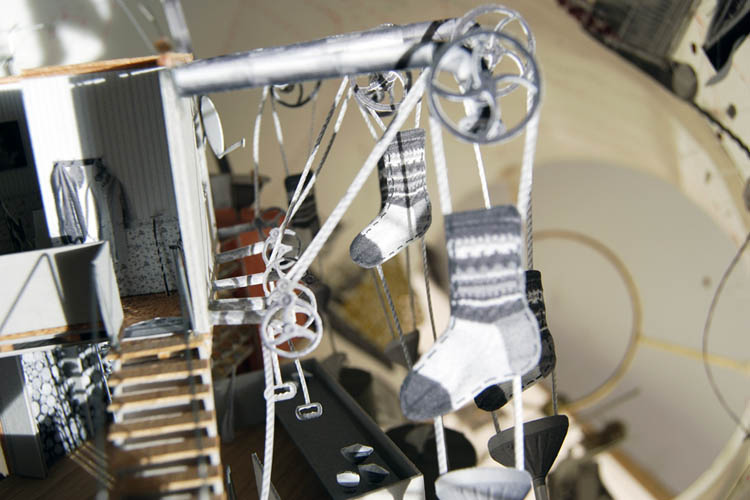

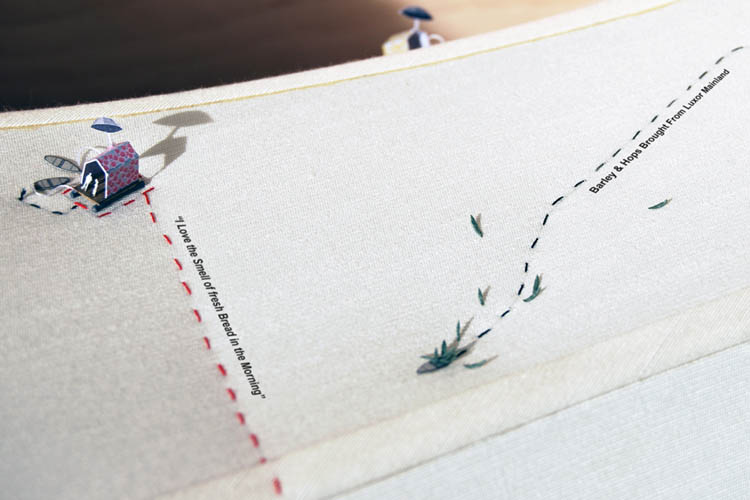

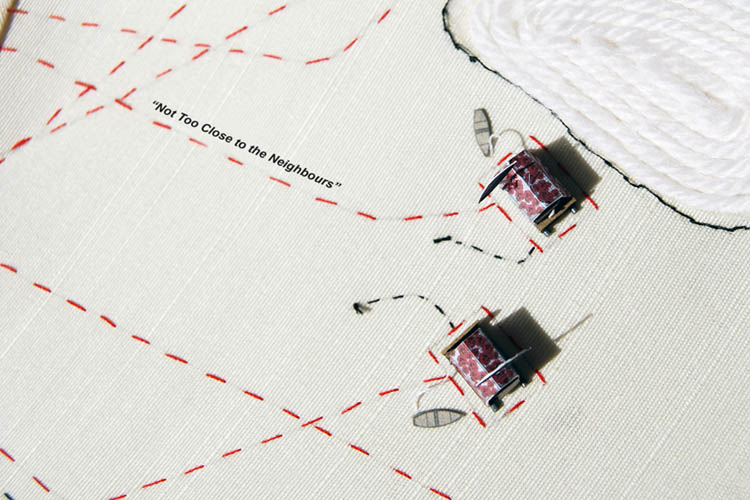

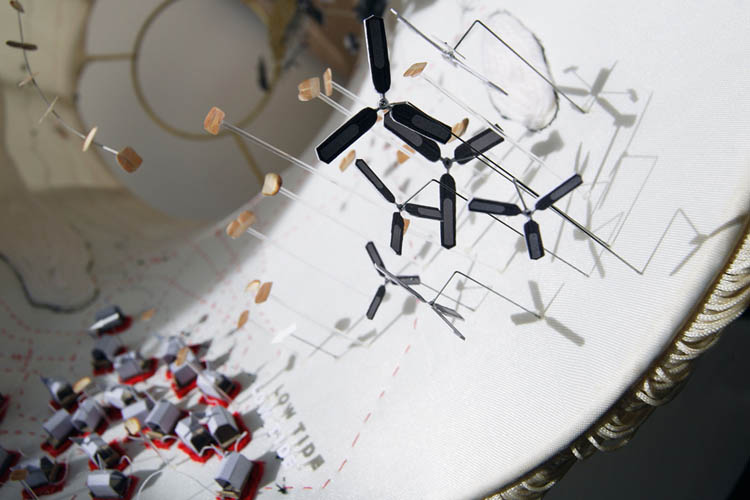

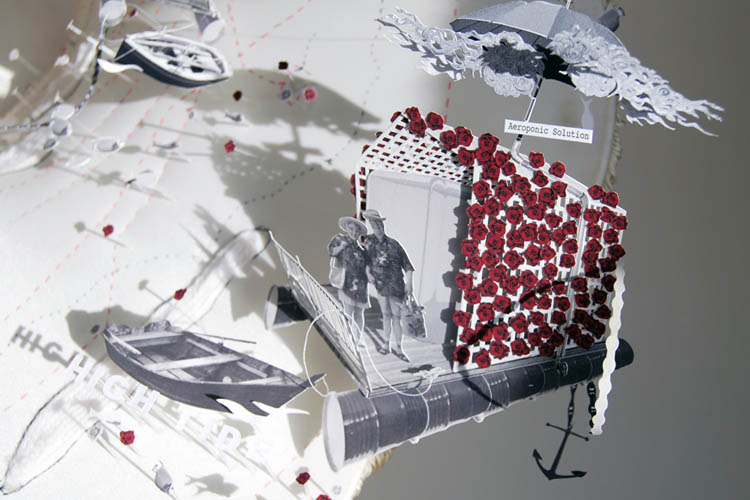

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

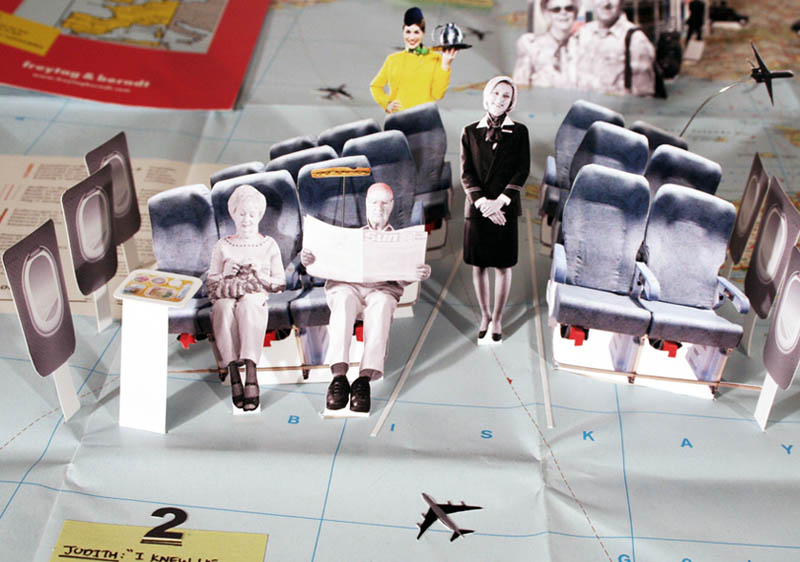

Thomas Hillier, of Emperor’s Castle fame, has sent in a newly documented but chronologically older project of his called “The Migration of Mel and Judith.”

“The Migration of Mel and Judith,” Hillier writes, “was the pre-cursor to The Emperor’s Castle and my first real exploration into using narrative as the vehicle for generating and scrutinizing my architectural ideas. It was also where I began using craft-based techniques and 2/3-dimensional assemblage to illustrate the design process.”

The Migration, though, is not only an entire storyline packaged inside a beautifully realized, miniature architectural world—it’s also told inside a lampshade.

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

Mel and Judith, Hillier explains, are “a recently retired couple from Croydon who have decided to give up on their life in London’s third City and travel Europe,” looking for a place to touch down for a while (and for better weather).

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

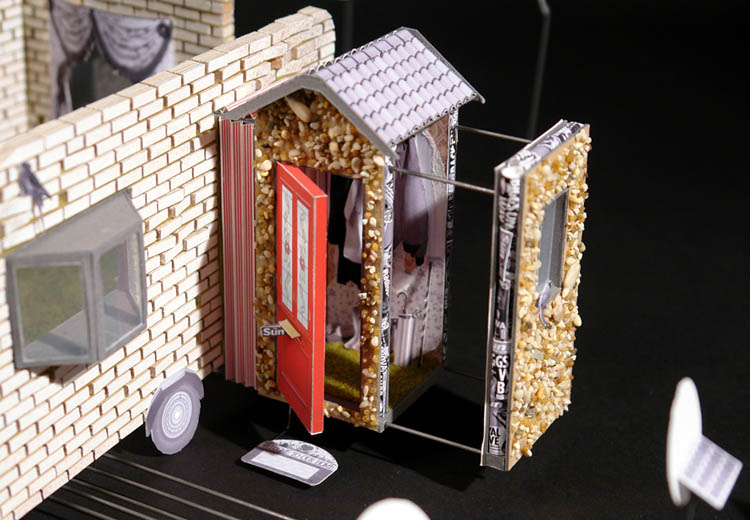

Soon enough, though, they get homesick—and the architectural transformation of their caravan-home begins:

To combat thier longing they slowly adapt and customise their caravan-house to feel a little more like home. Walls of the caravan become aroma filled bricks of white bread, especially made by Mel & Judith themselves. Other adaptations include the pebbledash façade reminiscent of their Croydon abode. A green lawn-carpet that is much cooler underfoot than the hot Marbella sand and when it gets too hot there’s always the sprinkler system and snow-chimney.

The couple’s mobile slice of English domesticity becomes all but entombed beneath the ornament of personal nostalgia.

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

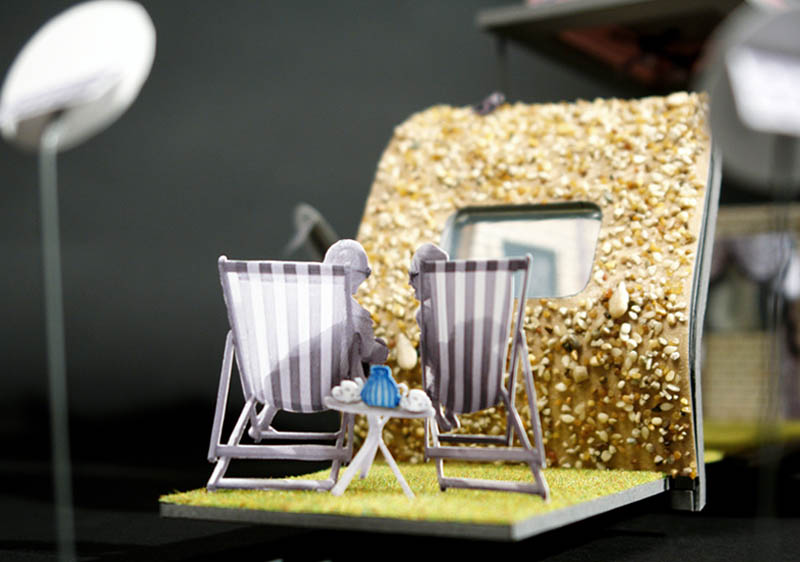

This, too, steeped in English nostalgia, becomes too staid for them, and the couple decides to leave Europe altogether, alighting for the more exotic climes of Luxor, Egypt.

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

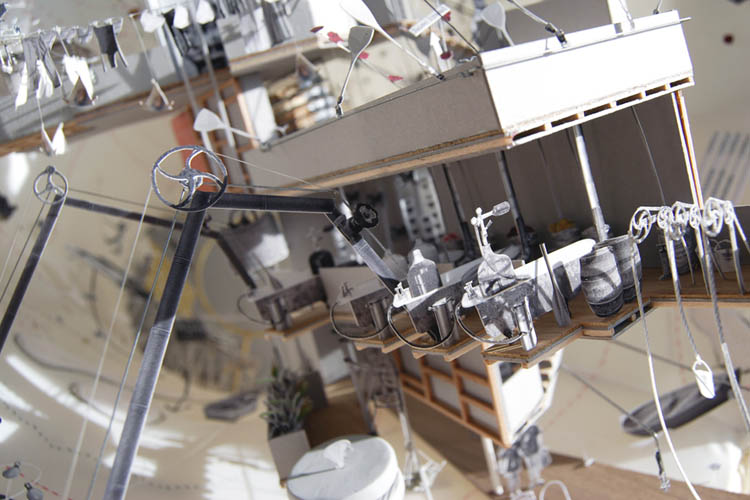

There, they settle “on a small, uninhabited island situated on the River Nile, where in their weird and wonderful ‘Do-It-Yourself’ English manor Mel brews beer in his bathtub-brewery whilst Judith bakes rose-bread in the bread-garden.”

Their island comes alive during the holiday season creating an English retreat in the middle of Luxor, a retreat that lures in English tourists with the opportunity to be surrounded by the sights, sounds and smells of home. The smell of roses and freshly baked bread drift through the air whilst the temptation to drink beer (which is illegal in Luxor) is impossible to resist.

Maps of riverine estuaries have thus been sewn into the lampshade alongside windfarms, fishing boats, photo-collages, and even a portrait of Princess Diana.

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

If you pull back, though, and look at the whole project within its physical and visual frame, the self-enclosed curling world of the lampshade adds a wonderfully anti-perspectival, frilly concavity to the couple’s journey. These latter scenes become both explosive and disorienting.

Like the spaceships in Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001, the walls of their representational frame simply turn and turn, bringing us over and over again back through the same space, as if unwilling to let go of what’s come before. Here, that space is asprawl with tidal flats and marshlands, fishing spots and coves. The couple, living now in Luxor, welcome visitors, dry their clothes aboard the boat deck, catch some afternoon sunlight, and grow old together, retired into this deliberately over-nostalgic world of their own making, constantly cycling back in memory through their shared past.

They have built a frame to fit themselves within, as if to give their lives narrative completion.

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by Thomas Hillier].

Check out The Emperor’s Castle, meanwhile, if you haven’t seen it already, and then click through to Hillier’s website.

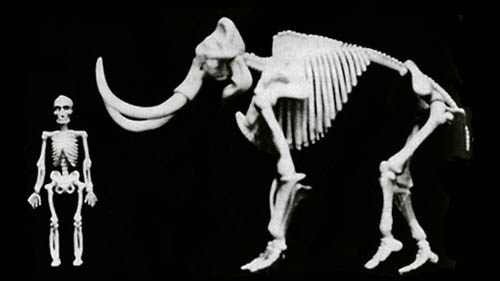

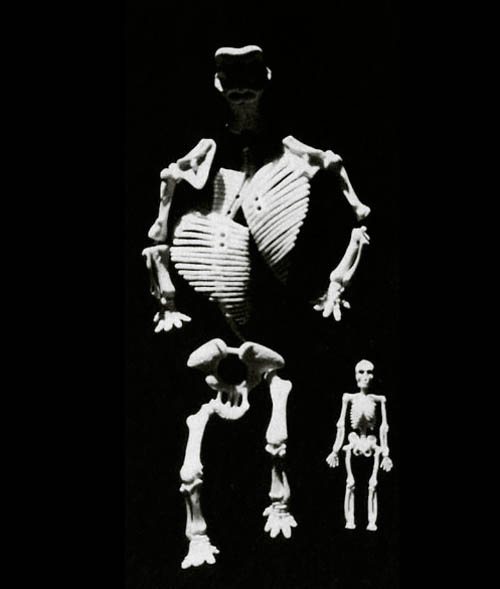

Bones of the Gigantomachy

In her excellent book The First Fossil Hunters, author Adrienne Mayor explains how Classical myths of giants, dragons, titans, heroes, and other ill-formed monstrous beings often stemmed from a misunderstanding of the fossil record. It was not at all infrequent for people of the time to have “striking personal experiences with giant skeletons that weathered out of the ground in Asia Minor,” Mayor writes, a place “where strange and immense skeletons emerge from the sand.” And, with no particular reason to assemble all those gigantic bones into animal forms with which humans had no direct experience, the bones were, instead, simply fashioned together to form titanic heroes. Gods on earth. Monstrous ancestry.

A mastodon skeleton, for instance, seen here in its proper assembly—

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

—was pieced together, instead, with Herculean proportions, towering over the human figure beside it.

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

[Image: From The First Fossil Hunters by Adrienne Mayor].

Heroes, titans, giants: eventually, in a time before human history, Mayor explains, a mythic war between the oversized dwellers of the Earth and the Gods themselves took place, called the Gigantomachy. Explosive battles left incomprehensible body parts scattered all over the land masses, where they were gradually buried by sand or stratigraphically entombed inside rocky cliffs.

Then humans came along, unversed in today’s anatomical principles, and assembled these giant bones into a lost and mutant history for themselves. And there you have Hercules, for instance, a mutant being accidentally assembled from the remnant skeletons of other creatures.

Quadraturin and Other Architectural Expansionary Tales

While I’m announcing things, I also want to give a heads up to anyone in the Los Angeles area that I’ll be lecturing on Wednesday evening, October 13th, over at SCI-Arc, speaking on the subject of “Quadraturin and Other Architectural Expansionary Tales.” I’ll be delving into the long-running subtheme on this site of the role of architectural ideas in poetry, myth, comics, and fiction, from the ancient to extreme futurity.

While I’m announcing things, I also want to give a heads up to anyone in the Los Angeles area that I’ll be lecturing on Wednesday evening, October 13th, over at SCI-Arc, speaking on the subject of “Quadraturin and Other Architectural Expansionary Tales.” I’ll be delving into the long-running subtheme on this site of the role of architectural ideas in poetry, myth, comics, and fiction, from the ancient to extreme futurity.

From “trap streets” in London and the fiction of China Miéville to the folklore of The First Fossil Hunters and myths of Alexander’s Gates—to, of course, Quadraturin—by way of Franz Kafka, Mike Mignola, Rupert Thomson, 3D-printing bees, haunted skyscrapers, neutrino storms, the Cyclonopedia, and much more, the talk will be a quick rundown of both the narrative implications of architecture and the architectural implications of specific storylines.

It’s free and open to the public, and there’s an insane amount of parking, so hopefully I will see some of you there. Here’s a map. Things kick off at 7pm.

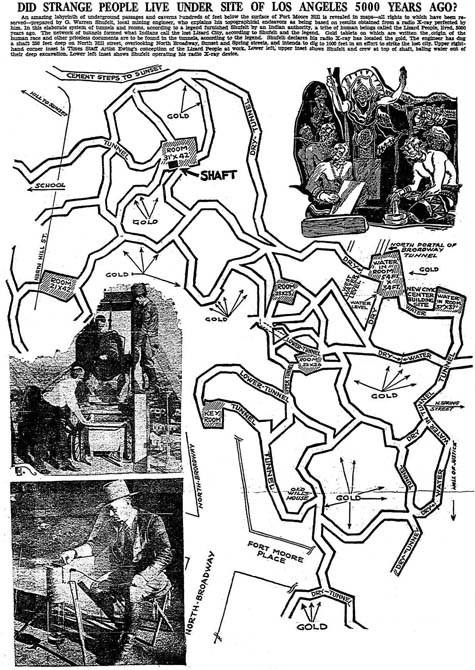

City Laid Out Like Lizard

[Image: View larger].

[Image: View larger].

Last week, Josh Williams, formerly of Curbed LA, emailed with an amazing link to an article, reportedly published back in 1934 by the L.A. Times, about a race of “lizard people” who once lived beneath the city.

“Did strange people live under site of Los Angeles 5000 years ago?” the article asks, supplying a bizarre treasure map through the city’s undersides in the process.

[Image: View larger].

[Image: View larger].

Although you can read the article in full through these links, I wanted to give you a taste of the story’s strange mix of gonzo archaeology, Poltergeist-like pre-Columbian cultural anxiety, and start-up geophysical investigation squad:

So firmly does [a “geophysical mining engineer” named G. Warren Shufelt] believe that a maze of catacombs and priceless golden tablets are to be found beneath downtown Los Angeles that the engineer and his aides have already driven a shaft 250 feet into the ground, the mouth of the shaft behind on the the old Banning property on North Hill Street overlooking Sunset Boulevard, Spring Street and North Broadway.

And so convinced is the engineer of the infallibility of a radio X-ray perfected by him for detecting the presence of minerals and tunnels below the surface of the ground, an apparatus with which he says he has traced a pattern of catacombs and vaults forming the lost city, that he plans to continue sending his shaft downward until he has reached a depth of 1000 feet before discontinuing operations.

The article goes on to suggest that this ancient subterranean city was “laid out like [a] lizard”; we visit a Hopi “medicine lodge,” wherein geophysical secrets are told; there are lost gold hoards; and, all along, the engineer’s “radio X-ray” apparatus continues to detect inhabitable voids beneath the metropolis.

“I knew I was over a pattern of tunnels,” Shufelt is quoted, “and I had mapped out the course of the tunnels, the position of large rooms scattered along the tunnel route, as well as the position of the deposits of gold, but I couldn’t understand the meaning of it.”

Perhaps this is what we’d get if Steven Spielberg hired Mike Mignola to write the next installment of Indiana Jones.

(Thanks to Josh Williams, and to vokoban, who originally uploaded the scan. Vaguely related: The Hollow Hills and Mysterious Chinese Tunnels).

The Comparative Literature of Massive Construction Sites

[Image: An etching by Daniel Stojkovich called Tower of Babel 2, exhibited as part of Top Arts 2007 at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia].

[Image: An etching by Daniel Stojkovich called Tower of Babel 2, exhibited as part of Top Arts 2007 at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia].

I was clicking around on a local university’s engineering school homepage yesterday morning when I misunderstood the way the page had been organized. For a second I thought that Comparative Literature had been re-classified as a sub-field, or specialty research group, within the university’s engineering school – and so I had to wonder what exactly those students might be reading.

Aside from technical manuals, what might be the comparative literature of engineering?

Before I realized that I’d simply misread the list of links, I thought that perhaps there should be a comparative literature of construction sites: famous monuments, tombs, bridges, houses, and cities throughout history, together with the thoughts of the people who built them.

You collect the oral histories of construction workers all over the world, only identifying what building they were working on in the footnotes; what emerges is a kind of architectural hivework with no clear purpose or outline taking shape all over the planet, with towers and stadiums and whole urban neighborhoods assembled in a fog of exhaustion and low-grade injury.

You then go back through all of literature, from the Bible to the Upanishads to The Odyssey to The New York Times, culling long quotations about construction sites. The private houses of emperors; the pyramids; recollections of the construction of jungle temples; mountain lookouts in a time of war; Victorian train lines; Dubai.

In fact, I’m reminded of the excellent book Dart by Alice Oswald in which conversations with people living along the river Dart have been combined into a single, long-running commentary about the riverine landscape; only here it would be a kind of Dart of architecture: thousands and thousands of construction workers and site engineers and geotechnicians and consultant elevator repair servicepersons all speaking about the act of putting architecture together in space.

Epic poems of building assembly.

I do wonder, meanwhile, if the temporary micro-culture of the construction site has been adequately documented by architectural historians. Industrial yards have certainly had their day, from documentaries about WWII dockworkers to historical surveys of Solidarity; and construction sites have obviously long been a focus for painters and photographers.

But have literature and history given the attention due to sites of architectural assembly?

Do we need a Construction Site Reader – the comparative literature of massive construction sites?

A Natural History of Mirrors

In his book Crystallography, poet Christian Bök describes “a medieval treatise on the use of mirrors.” This treatise, Bök tells us, suggests that when two mirrors reflect one other, the endless abyss of mirrors-in-mirrors created between them might form a kind of spectral architecture.

Further, Bök’s alleged medieval treatise says, “any living person who has no soul can actually step into either one of the mirrors as if it were an open door and thus walk down the illusory corridor that appears to recede forever into the depths of the glass by virtue of one mirror reflecting itself in the other. The walls of such a corridor are said to be made from invulnerable panes of crystal, beyond which lies a nullified dimension of such complexity that to view it is surely to go insane. The book also explains at length that, after an eternity of walking down such a corridor, a person eventually exits from the looking-glass opposite to the one first entered.”

Treatise’s author, according to Bök, “speculates that a soulless man might carry another pair of mirrors into such a corridor, thereby producing a hallway at right angles to the first one, and of course this procedure might be performed again and again in any of the corridors until an endless labyrinth of glass has been erected inside the first pair of mirrors, each mirror opening onto an extensive grid of crisscrossing hallways, some of which never intersect, despite their lengths being both infinite and perpendicular.”

The author of this hypothetical treatise warns, however, that one could become “hopelessly lost while exploring such a maze” – for instance, “if the initial pair of mirrors are disturbed so that they no longer reflect each other, thus suddenly obliterating the fragile foundation upon which the entire maze rests.”

In which case whole crystal cities of mirrored halls, in right-angled topologies of non-self-intersecting self-intersection, would simply disappear – along with anyone exploring inside them.

A kind of rogue experiment might ensue, aboard the International Space Station: an astronaut, crazed with loneliness, sets up two mirrors… and promptly escapes into a hinged labyrinth of crystallized earth-orbiters, his radio crackling unanswered in the control panel left behind.