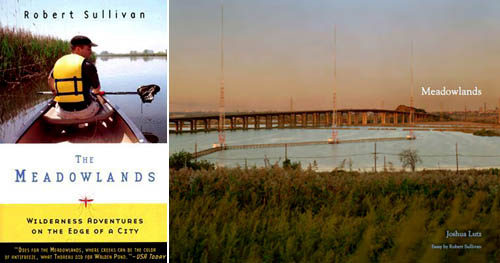

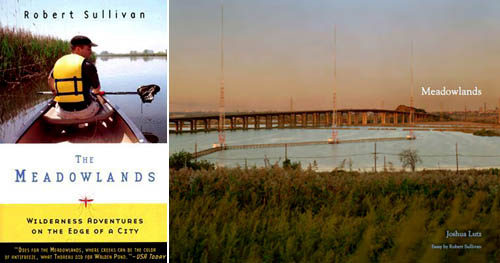

I’ve just finished reading The Meadowlands: Wilderness Adventures on the Edge of a City by Robert Sullivan, a book perfectly discussed in the visual context of Meadowlands, a collection of photographs by Joshua Lutz (for which Sullivan actually wrote an introduction).

[Image: From Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

[Image: From Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

“Just five miles west of New York City,” the back cover of Sullivan’s book reads, are the Meadowlands: “this vilified, half-developed, half-untamed, much dumped-on, and sometimes odiferous tract of swampland is home to rare birds and missing bodies, tranquil marshes and a major sports arena, burning garbage dumps and corporate headquarters, the remains of the original Penn Station, and maybe, just maybe, of the late Jimmy Hoffa.” It is “mysterious ground that is not yet guidebooked,” Sullivan writes inside, “where European landscape painters once set up their easels to paint the quiet tidal estuaries and old cedar swamps,” but where, now, “there are real hills in the Meadowlands and there are garbage hills. The real hills are outnumbered by the garbage hills.”

Lutz’s book describes the region as a “32-square-mile stretch of sweeping wilderness that evokes morbid fantasies of Mafia hits and buried remains.” As Lutz explained in a 2008 interview with Photoshelter, “When I first saw the Meadowlands I was completely blown away at this vast open space with the Manhattan skyline in the distance. It was this space that existed between spaces, somewhere between urban and suburban all the while made up of swamps, towns and intersecting highways. None of it made any sense to me, still doesn’t.”

All told, the area has become, Sullivan writes, “through negligence, through exploitation, and through its own chaotic persistence, explorable again.”

[Images: The Meadowlands: Wilderness Adventures on the Edge of a City by Robert Sullivan and Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

[Images: The Meadowlands: Wilderness Adventures on the Edge of a City by Robert Sullivan and Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

To write his book, Sullivan went on a series of explorations through the Meadowlands, including by canoe and in the company of a former police detective.

While there are definitely some moments of rhetorical over-kill, the book is so filled with interesting details that it proved very hard to stop reading; in between learning about the “discharged liquefied animal remains” that were dumped into the region’s streams and rivers, or the “major pet company and Meadowlands development firm” that “drove so many steel girders into the ground that people joked Secaucus would become a new magnetic pole,” or even the old—and, unfortunately, forgotten—mine shafts that began swallowing a development called the Schuyler Condominiums, Sullivan’s book, like any good and truly local history, builds to a level of narrative portraiture that is as braided and fractally involuted as the wetlands it documents.

[Image: From Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

[Image: From Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

For instance, Sullivan discovers a flooded radio transmission room, “its giant antenna felled in the water like a child’s broken toy,” as well as “little islands, composed wholly of reeds,” one of which, in the middle of soggy nowhere and accessible only by boat, was “surrounded by bright yellow police emergency tape: CAUTION, the tape said.”

Relating the litany of pollutions that exist in the swamps, he guides the reader’s eye toward ponds of cyanide, truckloads of “unregulated medical waste,” and soil so thoroughly contaminated with mercury that, “as recently as 1980, it was possible to dig a hole in the ground and watch it fill with balls of shiny silvery stuff.”

This might even have affected the New York Giants football team after they moved into Meadowlands Stadium: “In the mid-1980s, playing football in the Meadowlands meant possibly risking your life, because shortly after the stadium opened players for the Giants began developing cancer… ‘Players complained of occasionally foul-smelling water, and the high incidence of leukemia in adjacent Rutherford…'” No official medical link was either admitted or found. Indeed, certain streams are really a kind of “garbage juice”—an “espresso of refuse,” as Sullivan nauseatingly describes it.

In many places, the so-called ground is, in fact, trash—so much so that “underground fires are still common today… you can see little black holes where the hills have recently burped hot gases or fire… huge underground plumes of carbon dioxide and of warm moist methane, giant stillborn tropical winds that seep through the ground to feed the Meadowlands’ fires, or creep up into the atmosphere,” forming a particularly Dantean local climatology of reeking crosswinds. One of these fires “burned for fifteen years.”

[Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

[Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

The Meadowlands are, after all, a massive dump, more landfill than landscape. The effect, though, is a kind of new picturesque, an engineered sublime of artificial hills, deltaic chemical accumulants, cheap hotels overlooking it all on the periphery, and even entire lost buildings buried beneath three centuries of dumping. “If you put a shovel anywhere into the ground and dig just about anywhere in the Meadowlands,” Sullivan writes, “it won’t be long until you hit rubble from a building that was once somewhere else.”

In Kearny, one old dump contains pieces of what was once Europe. In 1941, under the auspices of the Lend-Lease Act, shipments of defense equipment went from the United States to Great Britain by boat. On their return trip, the boats used rubble from London bombings as ballast. William Keegan, a Kearny dump owner, contracted to accept the ballast. As a result, some of the hills of the Kearny Meadows are London Hills.

This is actually also true for New York’s FDR Drive, which is partially constructed on British war ruins used as fill.

[Image: An awesomely sinister photo from Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

[Image: An awesomely sinister photo from Meadowlands by Joshua Lutz].

There is an amazing chapter about mosquito control in the region, something I want to return to in a future post someday; another about treasure hunters on a quest for Revolutionary War-era gold and silver; and another about the construction of the hulking and monumental Pulaski Skyway. Before that oddly tunnel-like, 3.5-mile, elevated roadway was built, “ferries and sailboats took passengers from New York to Newark via Jersey City,” but, like something out of a Terry Gilliam film, “it was not unusual for papers to report that a ship making the trip had been blown out to sea and never been seen again.”

I could go on and on. There is even an entire subplot in which Sullivan hunts down the buried remains of New York’s Penn Station.

I want to end, though, with something said by the retired police detective who takes Sullivan under his wing on a series of driving tours toward the end of the book. When Sullivan asks the former investigator if he misses his job, the response is intelligent, thoughtful, and extraordinary. I’ll quote it in full:

“I miss it to this day, to this minute,” he said. “And do you know why? Because it takes you a long time to accumulate the knowledge.”

He pointed out the car. “Like for instance,” he continued, “look over there at that building, that warehouse. See how one door is open and one door looks like it’s closed up. Now, what I’ll do is store that. Keep it in my head. And see that sign over there in front of that building? You remember that. You remember that because you may need it someday. It may be useful. You accumulate the knowledge. Do you see what I mean? And then all of a sudden you’re supposed to just stop.”

He shook his head and started the car moving again, driving slowly up out of the swamp, up the hill. “The thing is, you just can’t,” he said.

This hermeneutic attention to everyday details—through which open warehouse doors or unusually parked cars all become raw data accumulated over decades for use in some later, possibly never-to-occur narrative dissection—is exactly the task not only of the detective but of the writer, and of anyone who would attempt to study an existing landscape in order to uncover its most unexpected and far-reaching implications.

In any case, together with Lutz’s photos of the region and its very particular anthropology—which Lutz discusses in an interview with Conscientious, remarking that the Meadowlands are “an astonishing mixture of towns, swamps, trains, motels and an amazing array of bisecting highways all trying to keep you out”—both books have been invigorating encounters over the past week or two, and each is worth checking out if you get the chance.

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via Wikimedia.]

[Image: A cockatoo in the background of Andrea Mantegna’s “Madonna della Vittoria” (1496), via Wikimedia.] [Image: From episode 9 of

[Image: From episode 9 of  [Image: From episode 9 of

[Image: From episode 9 of  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Illustration by

[Image: Illustration by

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: California’s Ivanpah Solar Energy Generating System photographed by

[Image: California’s Ivanpah Solar Energy Generating System photographed by

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Early rendering for

[Image: Early rendering for  [Image: Floating caisson during the construction of the original Bay Bridge; photo by Clyde Sunderland, courtesy

[Image: Floating caisson during the construction of the original Bay Bridge; photo by Clyde Sunderland, courtesy  [Image: Farming California, via Google Maps].

[Image: Farming California, via Google Maps]. [Image: Veduta dell’Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo (1776), by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; courtesy

[Image: Veduta dell’Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo (1776), by Giovanni Battista Piranesi; courtesy  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Image: Maria Thereza Alves’s Seeds of Change garden, via

[Image: The cover for

[Image: The cover for  [Image: The tree typeface from

[Image: The tree typeface from

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from

[Image: Borges, translated into trees, from  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  [Image: The introduced forestry of Ascension Island, via Google Maps].

[Image: The introduced forestry of Ascension Island, via Google Maps]. [Image: A suburban landscape being rolled out into the forest like carpet; photo by

[Image: A suburban landscape being rolled out into the forest like carpet; photo by

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Images:

[Images:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from

[Image: Bow-hunting amidst the reeds, from  [Image: An awesomely sinister photo from

[Image: An awesomely sinister photo from