[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

In a short story called “Reports of Certain Events in London” by China Miéville—a text often cited here on BLDGBLOG—we read about a spectral network of streets that appear and disappear around London like the static of a radio tuned between stations, old roadways that are neither here nor there, flickering on and off in the dead hours of the night.

For reasons mostly related to a bank heist described in my book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City, I found myself looking at a lot of aerial shots of Los Angeles—specifically the area between West Hollywood and Sunset Boulevard—when I noticed this weird diagonal line cutting through the neighborhood.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

It is not a street—although it obviously started off as a street. In fact, parts of it today are still called Marshfield Way.

At times, however, it’s just an alleyway behind other buildings, or even just a narrow parking lot tucked in at the edge of someone else’s property line.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

Other times, it actually takes on solidity and mass in the form of oddly skewed, diagonal slashes of houses.

The buildings that fill it look more like scar tissue, bubbling up to cover a void left behind by something else’s absence.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

First of all, I love the idea that the buildings seen here take their form from a lost street—that an old throughway since scrubbed from the surface of Los Angeles has reappeared in the form of contemporary architectural space.

That is, someone’s living room is actually shaped the way it is not because of something peculiar to architectural history, but because of a ghost street, or the wall of perhaps your very own bedroom takes its angle from a right of way that, for whatever reason, long ago disappeared.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

If you follow this thing from roughly the intersection of Hollywood & La Brea to the strangely cleaved back of an apartment building on Ogden Drive—the void left by this lost street, incredibly, now takes the form of a private swimming pool—these buildings seem to plow through the neighborhood like train cars.

Which could also be quite appropriate, as this superficial wound on the skin of the city is most likely a former streetcar route.

But who knows: my own research went no deeper than an abandoned Google search, and I was actually more curious what other people thought this might be or what they’ve experienced here, assuming at least someone in the world reading this post someday might live or work in one of these buildings.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

And perhaps this is just the exact same point, repeated, but the notion that every city has these deeper wounds and removals that nonetheless never disappear is just incredible to me. You cut something out—and it becomes a building a generation later. You remove an entire street—and it becomes someone’s living room.

I remember first learning that one of the auditoriums at the Barbican Art Centre in London is shaped the way it is because it was built inside a former WWII bomb crater, and simply reeling at the notion that all of these negative spaces left scattered and invisible around the city could take on architectural form.

Like ghosts appearing out of nowhere—or like China Miéville’s fluttering half-streets, conjured out of the urban injuries we all live within and too easily mistake for property lines and real estate, amidst architectural incisions that someday become swimming pools and parking lots.

*Update* Some further “ghost streets” have popped up in the comments here, and the images are worth posting.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

The one seen above, for example, is “another ghost diagonal that begins on 8th St. at Hobart, and ends at Pico and Rimpau,” an anonymous commenter explains.

Another example, seen below—

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

—is “a block in the Pico-Robertson area,” a commenter writes:

I lived there as a teenager, but never noticed the two diagonals until I looked at it with google maps. There are some lots on the west side of the next two blocks north which also have diagonals. And if you continue north across Pico Blvd, you can see diagonal property lines around St. Mary Magdalene Catholic School and the church.

Thanks for all the tips, and by all means keep them coming, if you are aware of other sites like this, whether in Los Angeles or further afield; and be sure to read through the comments for more.

*Second Update* The examples keep coming. A commenter named Lance Morris explains that he did an MFA project “about this very thing, but in Long Beach. There’s a long diagonal scar running from Long Beach Blvd and Willow all the way down to Belmont Shore. I tried walking as closely to the line as I could and GPS tracked the results. There are even 2 areas where you can still see tracks!”

This inspired me to look around the area a little bit on Google Maps, which led to another place nearby, as seen below.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

Again, seeing how these local building forms have been generated by the outlines of a missing street or streetcar line is pretty astonishing.

Further, the tiniest indicators of these lost throughways remain visible from above, usually in the form of triangular building cuts or geometrically odd storage yards and parking lots. Because they all align—like some strange industrial ley line—you can deduce that an older piece of transportation infrastructure is now missing.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view a bit larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view a bit larger].

Indeed, if you zoom out from there in the map, you’ll see that the subtle diagonal line cutting across the above image (from the lower left to the upper right) is, in fact, an old rail right of way that leads from the shore further inland.

To give a sense of how incredibly subtle some of these signs can be, the diagonal fence seen in the below screen grab—

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

—is actually shaped that way not because of some quirk of the local storage lot manager, but because it follows this lost right of way.

*Third Update* There are yet more interesting examples popping up now over in a thread on Metafilter.

There, among other notable comments, someone called univac points out that the streetcar scar that “begins on 8th St. at Hobart, and ends at Pico and Rimpau”—quoting an earlier commenter here on BLDGBLOG—”actually has one echo in the diagonally-stepped building here, and picks up again in the block bounded by Wilton, Westchester, 9th and San Marino, and ends at a crooked building just north of 4th and Olympic.”

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

You can see the middle stretch of that route in the image, above. For more, check out the thread on Metafilter.

Not only this, however, but the old right of way followed by that commenter actually extends much further than that, all the way southwest to a small park at approximately Pico and Queen Anne Place.

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

[Image: Via Google Maps; view larger].

In the above image, you can see a small structure—a garage or a house—turned slightly off-axis in the northeast corner, indicating the line of the old streetcar line, with some open lawns and small paved areas revealing its obscured geometry as you look down to the southwest.

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

This is purely promotional, but I wanted to mention that I am up in San Francisco for two nights to speak as part of

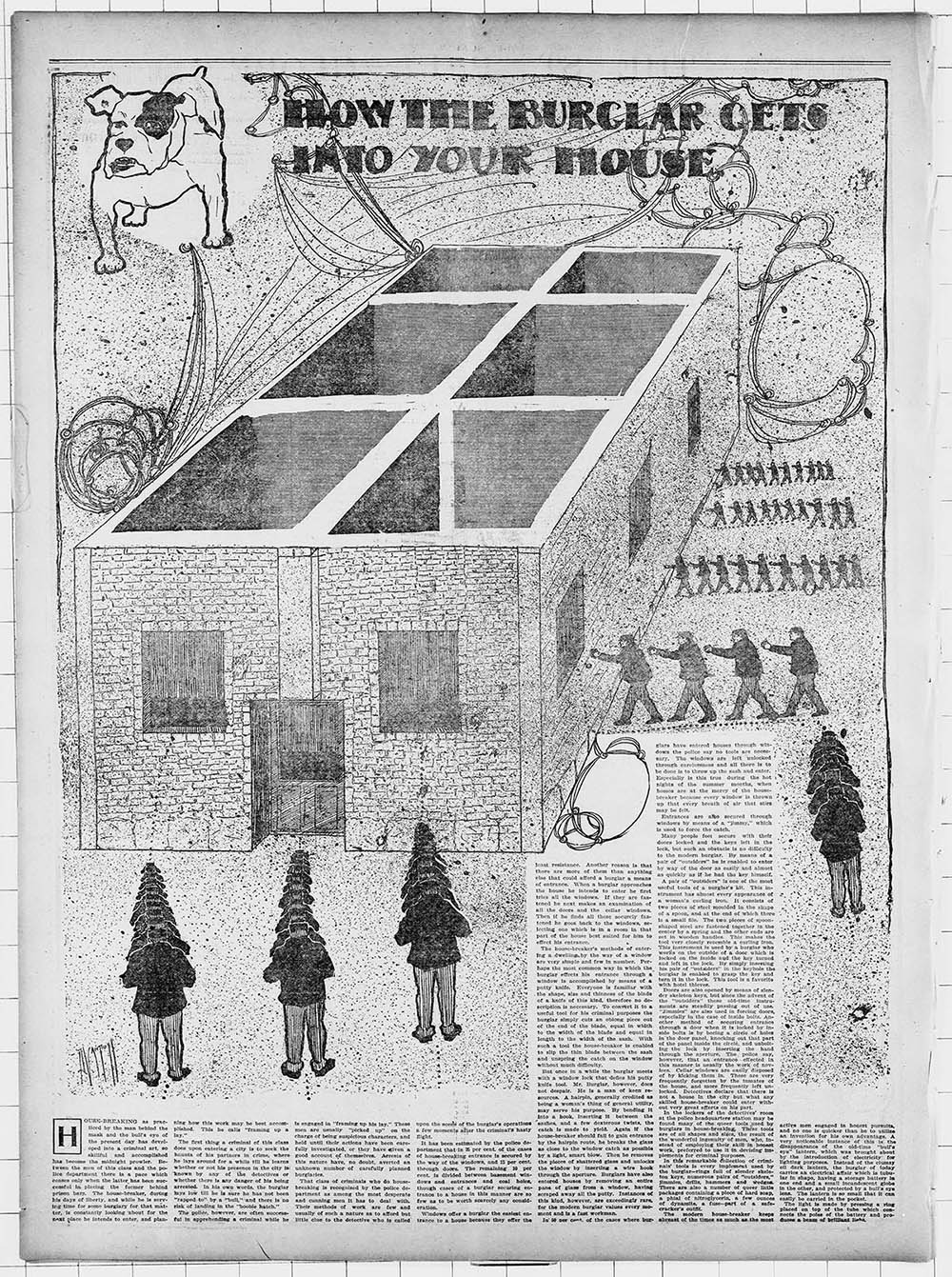

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via  [Image: A street in Athens, via

[Image: A street in Athens, via  [Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’

Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’  [Image: Unrelated surveillance footage].

[Image: Unrelated surveillance footage]. The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.

The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.  [Image: Published in the New York Tribune, September 11, 1910].

[Image: Published in the New York Tribune, September 11, 1910].

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: From

[Image: From