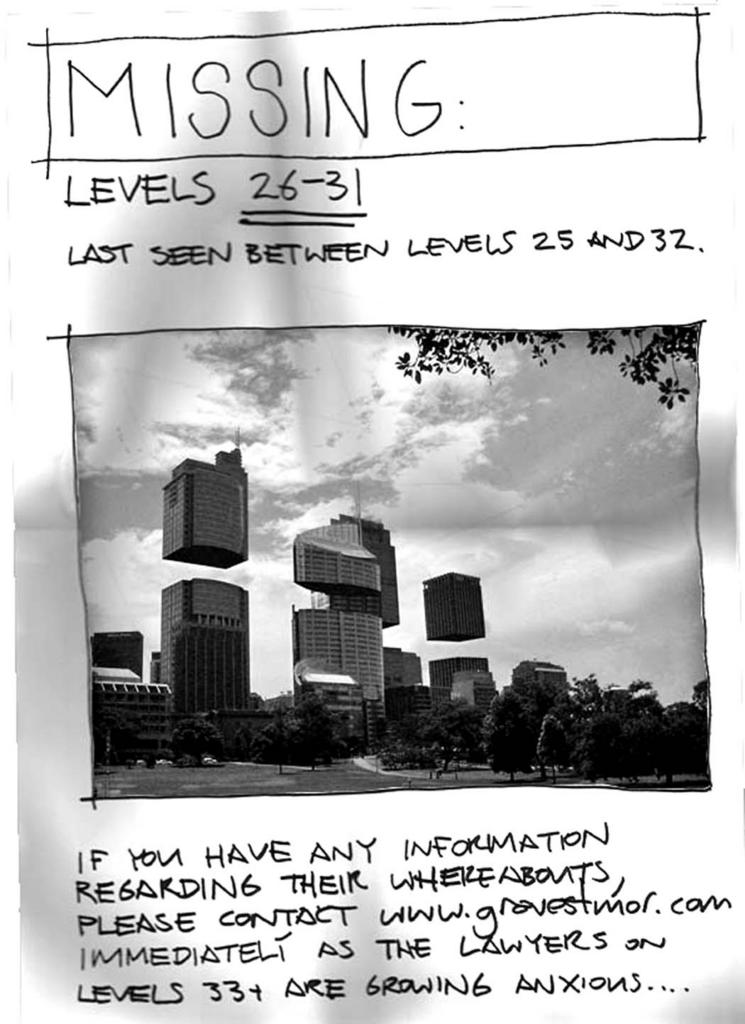

From, and by, gravestmor. You can hardly tell from the size of the image here, but it’s very well-done…

From, and by, gravestmor. You can hardly tell from the size of the image here, but it’s very well-done…

Sound dunes

“Sand dunes in certain parts of the world are notorious for the noises they make,” New Scientist reports, “as sand avalanches down their sides. Some [dunes] emit low powerful booms, others sound like drum rolls or galloping horses, and some are even tuneful. These dune songs have been reported to last for up to 15 minutes and can sound as loud as a low-flying airplane.”

To test for the causes, properties, and other effects of these sand dune booms, “Stéphane Douady of the French national research agency CNRS and his colleagues shipped sand from Moroccan singing dunes back to his lab to investigate.” There, Douady’s team “found that they could play notes by pushing the sand by hand, or with a metal handle.”

The transformation of a sand dune – and, by extension, the entire Sahara desert, indeed any desert – even, by extension, the rust deserts of Mars – into a musical instrument. Music of the spheres, indeed.

“When the sand avalanches, the grains jostle each other at different frequencies, setting up standing waves in the cascading layer, says Douady. These waves reinforce one another, making the layer vibrate like the surface of a loud speaker. ‘What’s funny is that in these massive dunes, only a thin layer of 2 or 3 centimetres is needed to set up the resonance,’ says Douady. ‘Soon all grains begin to vibrate in step.'”

Douady has so perfected his technique of dune resonance that he has now “successfully predicted the notes emitted by dunes in Morocco, Chile and the US simply by measuring the size of the grains they contain.” The music of the dunes, in other words, was determined entirely by the size, shape, and roughness of the sand grains involved, where excessive smoothness dampened the dunes’ sound.

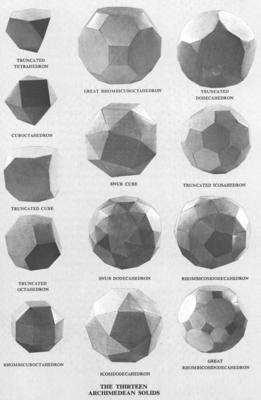

I’m reminded of the coast of Inishowen, a peninsula south of Malin Head in the north of Ireland, where the rocks endlessly grind across one another in the backwash of heaving, metallic, grey Atlantic waves. Under constant pressure of the oceanic, the rocks carve into themselves and each other, chipping down over decades into perfectly polished and rounded spheres, columns, and eggs – as if Archimedean solids or the nested orbits of Kepler could be discovered on the Irish ocean foreshore –

– all glittering. The rocks, I later learned, were actually semi-precious stones, and I had a kind of weird epiphany, standing there above the hush and clatter of bejewelled rocks, rubbing and rubbed one to the other in the depopulated void of a coastal November. It was not a sound easy to forget.

Because the earth itself is already a musical instrument: there is “a deep, low-frequency rumble that is present in the ground even when there are no earthquakes happening. Dubbed the ‘Earth’s hum‘, the signal had gone unnoticed in previous studies because it looked like noise in the data.”

Elsewhere: “Competing with the natural emissions from stars and other celestial objects, our Earth sings like a canary – it drones on in a constant hum of a gazillion notes. If it were several octaves higher, and hence, audible to the human ear,” it could probably get recorded by the unpredictably omnidirectional antennas of ShortWaveMusic and… you could download the sound of the earth. Free Radio Interterrestrial. [Note: the “drones on” link, a sentence or two back, offers a contrary theory (published in 2000) about the origins of these planetary sound waves.]

Which, finally, brings us to Ernst Chladni and his Chladni figures, or: architectonic structures appearing in sand due to patterns of acoustic resonance. The architecture of sand, involving sound—or architecture through sound, involving sand. Silicon assuming structure, humming.

The gist of Chladni’s experiments involved spreading a thin layer of sand across a vibrating plate, changing the frequency at which the plate vibrated, and then watching the sand as it shivered round, forming regular, highly geometric patterns. Those patterns depended upon, and were formed in response to, whatever vibration frequency it was that Chladni chose.

So you’ve got sand, dune music, terrestrial vibration, some Chladni figures – one could be excused for wondering whether the earth, apparently a kind of carbon-ironic bell made of continental plates and oceanic resonators, is really a vast Chladni plate, vibrating every little mineral, every pebble, every grain of sand, perhaps every organic molecule, into complex, three-dimensional, time-persistent patterns for which we have no standard or even technique of measurement. Or maybe William Blake knew how to do it, or Pythagoras, or perhaps even Nikola Tesla, but…

The sound dunes continue to boom and shiver. The deserts roar. The continents hum.

Soil-bombing Iceland

The Soil Conservation Service of Iceland is in the midst of a rather heroic effort to de-desertify large parts of the country. Iceland, in fact, is the largest desert in all of Europe.

As the BBC says, “The only difference [between the Icelandic desert and] the Sahara is that the sand here is black. Pitch black – with glaciers towering above and the sea shimmering in the distance. And the wind howling in between.” Which sounds like quite a difference.

In any case, the desert’s origins are with human activity; it is an artificial landscape, bearing traces of the island nation’s earlier inhabitants: “Despite the rather frightening name of the country, Iceland was green when Vikings came to settle. About 60% of the country was covered in bushes, trees, grass and all that. (…) But the Vikings, aside from chopping down trees for their own needs, also brought along their sheep. And what do sheep do best? They eat anything that is green.”

What interests me here, aside from the ecological message – don’t overgraze your territory – is the Soil Conservation Service’s preferred method of re-seeding: they pack finely sorted and organized seeds – virtual ecosystems, yet to occur, chosen species by species – into bombs: “Iceland is big and sparsely populated. There are few roads. So, Icelanders decided to ‘bomb their own country’, dropping the fertiliser and seeds from a WW II DC 3 Dakota.”

Earth, delivered by warplane.

(You can also listen to this story, as I first did, through an often irritating BBC podcast.)

So the bombs collide with the planet, releasing condensed and virtual landscapes: seed-bombs. Soil-bombs. The Icelandic countryside soon becomes an ironic inversion of a warzone: where the bombs fall, trees, grass, and wildflowers grow.

Instead of the lunar landscape of the Nevada test site, for instance—

—you get the opposite: strange oases of green, or gardening by artillery.

Which, conveniently, brings me to a new BLDGBLOG project.

It’s a landscape proposal: Artillery Gardens.

Unfortunately, there already is, in London, a place called Artillery Gardens, but no matter. BLDGBLOG’s Artillery Gardens will require the following: a very large parcel of land; a Howitzer; several shotguns; a military engineer who can calculate launching arcs and target distances; and some seed-packing volunteers, preferably experienced gardeners. Constant gardeners, perhaps. Everyone would fill up as many shotgun shells and old Howitzer cases as they could, using odd, rare, or otherwise exciting combinations of exotic seed; we’d all don some earplugs; and then it could begin: you’d blast a garden into existence.

Landscape planning as field artillery calculation. Landscape-at-a-distance. Gardening by artillery.

Through explosion and gunfire and heavy artillery, a rare and fragile garden is born. Species by species, day by day, through blast radii and impact fields, with the “power of endless growth and self-reproduction,” these Artillery Gardens will grow.

War as a garden, pursued by other means.

Das Urpflanze Haus

In what is, by now, a very old Wired blurb, you can read about Stoner Age artist and alien implant conspiracist Paul Laffoley, apparently a trained architect, who has proposed “genetically engineered seeds as a solution to the housing shortage.”

The seeds, you see, would grow into plants, and those plants themselves would grow into the shapes of inhabitable buildings. They would actually be buildings. Imagine a rather light-headed Michael Crichton watching *Swiss Family Robinson* on DVD when Rem Koolhaas stops by – and you’d get what Paul Laffoley has named das Urpflanze Haus, or “the primordial plant house.”

[Image: the Urpflanze Haus… so small you can barely see it, however.]

You’d plant the seeds – or perhaps just one, like a new, Piranesian “Jack and the Beanstalk” – do some watering, perhaps spread a little fertilizer… and at some point your own house will grow.

Thomas De Quincey: “With the same power of endless growth and self-reproduction did my architecture proceed in dreams.”

But what then? Do you prune excess or unwanted rooms? Can you graft new floorplans into the tree’s genetic code?

And will you get sap all over your FCUKing clothes?

Instead of topiary gardens, rich feudal warlords of the somewhat immediate future, with coked-up guards patrolling razorwire perimeters holding AK-47s and driving stolen Humvees, will cultivate delicate architectural gardens full of intertwined Urpflanze Häusen, on well-watered terraces stretching off past the conflict-laden, desert horizon. The world’s eventual oldest living house will be planted by a fourteen year-old girl in the hills of Missouri, out-living the Anthropocene by uncountable hundreds of years.

“Laffoley’s portfolio,” Wired continues, which “includ[es] a human-powered vehicle and a time machine, echoes the weird science of Nikola Tesla and Buckminster Fuller: Intricate illustrations and collages graft ancient occultism, eccentric engineering, particle physics, and a dose of ufology onto obsessively detailed building plans for a surreal alternative future.”

Privateering America’s prisons, or: “criminal aliens needing beds”

The Economist recently published a short article about the privatization of the US prison system, a process being led by “America’s largest private prison operator, the Nashville-based Corrections Corps of America (CCA).” That company has a massive base of operation; indeed, we are told, with no apparent sense of irony, that its “potential market is growing all the time.”

“America now has 726 prison inmates for every 100,000 people, compared with 142 in England, 91 in France and 58 in Japan. With public prisons notoriously overstretched, private prisons have been quietly picking up the slack since the Reagan years.” No mention is made, however, of the impact that federal law enforcement practices have had on the rise of prison populations during and since that time, or of the role of race in disproportionate sentencing – the author, in fact, refers rather oddly to “a regrettable shortage of inmates at some facilities,” which even in its original context raises eyebrows.

Incredibly, the article seems to look at private prisons as a new source of housing.

Housing? For illegal immigrants. This “potential market” is referred to – almost fantastically – as “criminal aliens needing beds.” According to the article, “a surge in criminal aliens needing beds helped save CCA five years ago.” (Needing beds? Were they drunk?)

Private prisons, capacity problems, criminal aliens needing beds…

One of the ways the CCA plans to stay afloat and save itself money is through sacking people – a strategy which seems to have got them into trouble. According to a recent headline in Correctional News, yessir, “Private Prison Operators Overcharged State $13 Million.” “CCA and GEO were paid an extra $4.5 million because CPC did not require the companies to report position vacancies during most of the time the contracts were in effect. When position vacancies were reported, monthly per-diem payments were not reduced.”

So of course firing people was lucrative – those people never left the payroll. As John Ferguson, CEO of CCA, tells The Economist, “The public sector tends not to eliminate positions when they’re not needed” – which may, of course, be true, but: 1) we’ve just seen how CCA interprets that information; and 2) what actually interests me here are the architectural implications: building a prison without guards.

The “panopticon” is such an obvious reference point here that I’ll just skip it – though I do have two images:

![]()

![]()

In any case, the uneasy implication of an ascendant private prison industry, at least in the context of saving money through sacking people, is that, in several years, almost literally anything a human guard can do will simply be replaced, automated, and tax-deducted through and by the architecture itself. Or perhaps infrastructure is a more accurate word, but the point is that the building, the physical prison, will become more and more of an electronically automated total environment, overseen through tele-surveillance – in which case private prisons will effectively become like that game *Doom*, or that ridiculous movie *Cube*, or even that other ridiculous movie, *Fortress*, about “the Fortress, a maximum security prison run by a computer and a mysterious warden…” Which almost sounds like soft porn.

My point is that the economic policies behind prison privatization will, by necessity, exhibit effects in the realm of architectural design.

Where human resources, quote-unquote, could have taken care of certain administrative and organizational problems, and done so rather simply, the architecture itself will soon be required to step up to the plate and perform.

Will we see private prisons at the avant-garde of building automation? More to the point, do we already?

[Image: Piranesi’s prison fantasies – automated environments of drawbridges and wheels, arches and guardless vaults.]

BLDGBLOG: Architecturally Reviewed

Somewhat unbelievably, BLDGBLOG was just featured in the August 2005 issue of The Architectural Review (on page 105). For ease of reference, and because I’m clearly not at all moved by this journalistic appearance, I’ve scanned, cropped, contrast-corrected, highlighted, digitally archived, and, now, uploaded images of that review for your reading pleasure…:

That post – Lunar urbanism – can be found here.

Then the next mention is longer, but it’s kind of in the middle of the column, so the beginning and end of the following excerpt don’t make much sense (as per your standard BLDGBLOG post), but…:

Thanks to David Cuthbert at Architechnophilia for pointing this out to me.

White men shining lights into the sky

[Image, Michael Kamber, NYTimes: Check out the rocket imagery in this wall mural, how the rocket itself appears to be part of a mosque & minaret or even Taj Mahal-like architectural complex, complete with Russian Constructivist telecommunications satellite (and is that the Eiffel Tower on the left?) – but it’s the rocket-as-minaret that really does it for me, with its theological appropriation of space exploration architecture. Retro-Futurist Interstellar Islam.]

[Image, Michael Kamber, NYTimes: Check out the rocket imagery in this wall mural, how the rocket itself appears to be part of a mosque & minaret or even Taj Mahal-like architectural complex, complete with Russian Constructivist telecommunications satellite (and is that the Eiffel Tower on the left?) – but it’s the rocket-as-minaret that really does it for me, with its theological appropriation of space exploration architecture. Retro-Futurist Interstellar Islam.]

In what is surely one of the most fascinating, if short, articles to be published recently in the New York Times, we read about a runway in Baafuloto, Gambia, once rented by NASA to act as a “transatlantic abort landing site” – one of several back-up runways, in fact, located around the world in case of emergency space shuttle landings.

The foreigners who would descend on this village… set up giant lights in the middle of an overgrown field and pointed them toward the sky. They stood in front of electronic screens powered by generators and talked hurriedly into radios hanging from their hips.

But for the local residents who saw them come and go over the years, the visitors always behaved most strangely just before they packed up and left Baafuloto. They would bustle about and then suddenly clap their hands and shout.

Sanjaney Saidy, 29, was a night watchman for the foreigners, known as tubabou in the local Mandinka language, thrilled with the roughly $2 a night he was paid, and proud of his uniform: boots, dark pants and a light blue shirt with a shoulder patch bearing the name of his employer – NASA.

“It’s a company, but I don’t know what they do,” said Mr. Saidy, who was 14 when he first worked for the Americans. “They told me to guard the lights, but I didn’t know the purpose.” The lights in Baafuloto, a mile or so from Banjul International Airport in Gambia, would help a shuttle in an aborted ascent find its way back to Earth.

And it gets better: Lasanna Saidy, the chief of Baafuloto, quite sensibly decided to go ahead and ask NASA what the lights were actually for: “‘When I asked them about the lights, they pointed up in the sky,’ the 75-year-old chief said. ‘They said there was a door in the sky and that their big plane might come through the door. They said the lights would help the plane, but I never did see it.'”

Then we read about NASA’s socio-medical reinvention of the car park (or landscape design as quarantine strategy for low earth-orbiting objects); in other words, “NASA built a parking area at Banjul’s airport to isolate the shuttle in case it came down spewing hazardous substances.”

In any case, NASA’s moved on from Baafuloto – because they have “another emergency landing site in Africa, [at] an abandoned Strategic Air Command base near Ben Guerir, Morocco.” But someone needs to send this to J.G. Ballard, because I think he’s already written that novel…

Can a novelist sue NASA for making his or her own fictional future come true?

Podcasting the sun

[Image: Helioseismology, or earthquakes on the sun (because “Sunquakes” would sound too much like a breakfast cereal…)]

“Have you ever wondered,” the Stanford-Lockheed Institute for Space Research asks, “what the Sun would sound like if you could hear it?” Why yes.

Luckily, you can now listen to “sun sounds,” courtesy of the SOHO Michelson Doppler Imager (MDI) project, “part of an international collaboration to study the interior structure and dynamics of the Sun” – including what the sun sounds like.

[Image: Computer simulation of the sun’s convective interior]

As you probably know, “the Sun is essentially spherical” – but this also means that it “forms a spherical acoustical resonator with millions of different normal modes of oscillation. Due to the waves’ long life times, destructive interference filters out all but the resonant frequencies, transforming the random convective noise into a very rich line spectrum in the five-minute range. Thus, convection acts rather like a random clapper causing the Sun to ring like a bell.”

To measure these oscillations – indeed, to listen to the sun “ring[ing] like a bell” – a whole new kind of densely connected, architectural network is required: “an uneclipsed instrument in space, observatories at the Earth’s poles, and a network of observatories around the Earth.”

All of these, of course, would need unimpeded sonic access to the solar “clapping.”

[Image: The Wilcox Solar Observatory]

The sun can be listened to indirectly, of course, in the form of solar storms interfering with terrestrial radio and television broadcasts – which brings to mind the story of how radio astronomy was first discovered, at Bell Labs in New Jersey. Thinking that his antenna was generating its own heat and noise, and therefore interfering with the experiment at hand (which I believe had something to do with telephones: discovering the universe by telephone), Karl Jansky eventually realized that all that white noise was *coming from deep space* – it was the sound of stars – and that he had discovered the radio-noise background in which our entire universe hums, eternally, at every second of every day, a kind of quiet hiss or whisper that we now know is an omnipresent sonic fossil left over from the Big Bang.

Space is full of sounds.

It was reported by Reuters, for instance, almost exactly two years ago, that a “particularly monstrous black hole has probably been humming B-flat for billions of years, but at a pitch no human could hear, let alone sing” – and that scientists “believe it is the deepest note ever detected in the universe.”

“As the black hole pulls material in, [Andrew Fabian of the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge, England] said, it also creates jets of material shooting out above and below it, and it is these powerful jets that create the pressure that creates the sound waves.”

Seismology in B-flat.

Or – similarly, about two years ago – the consistently exciting magazine New Scientist revealed that the Big Bang sounded “rather like a large jet plane flying 100 feet above your house in the middle of the night”: “Giant sound waves propagated through the blazing hot matter that filled the Universe shortly after the Big Bang. These squeezed and stretched matter, heating the compressed regions and cooling the rarefied ones. Even though the Universe has been expanding and cooling ever since, the sound waves have left their imprint as temperature variations on the afterglow of the big bang fireball, the so-called cosmic microwave background.”

Enter Karl Jansky and his broken telephone, throw in some helioseismology – and you get landscapes of noise, in deep space.

(For some gorgeous MP3s of global shortwave radio music, full of radio hiss and strange sidereal cross-broadcasts – the sun whispering to itself, drenched in light – see the blog ShortWaveMusic; and for another post on a similar theme, see Radio Haloes of Earth).

[Image: This is actually a satellite measuring the earth’s magnetic field, but…]

Katrina 3: Two Anti-Hurricane Projects (on landscape climatology)

Project 1: “How do you slow down a hurricane?”

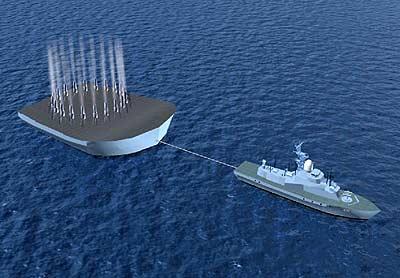

In the June 2005 edition of The Economist Technology Quarterly (subscription required), we read about Moshe Alamaro, “a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, [who] has a plan. Just as setting small, controlled fires can stop forest fires by robbing them of fuel, he proposes the creation of small, man-made tropical cyclones to cool the ocean and rob big, natural hurricanes of their source of energy. His scheme, devised with German and Russian weather scientists and presented at a weather-modification conference in April, involves a chain of offshore barges adorned with upward-facing jet engines.”

“Each barge creates an updraft, causing water to evaporate from the ocean’s surface and reducing its temperature. The resulting tropical storms travel towards the shore but dissipate harmlessly. Dr Alamaro reckons that protecting Central America and the southern United States from hurricanes would cost less than $1 billion a year. Most of the cost would be fuel: large jet engines, he observes, are abundant in the graveyards of American and Soviet long-range bombers.”

The creation of manmade tropical micro-storms, using heavy, greenhouse gas-burning jet engines towed through the waters of the equatorial Atlantic on what are, for all intents, artificial islands… is really a pretty ridiculous idea.

Yet it reminds me of a long-standing BLDGBLOG project that has otherwise gone unpublished. Till now:

Project 2: The Aeolian Reef

In Virgil’s *Aeneid*, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, we read about “Aeolia, the weather-breeding isle”:

“Here in a vast cavern King Aeolus

Rules the contending winds and moaning gales

As warden of their prison. Round the walls

They chafe and bluster underground. The din

Makes a great mountain murmur overhead.

High on a citadel enthroned,

Scepter in hand, he molifies their fury,

Else they might flay the sea and sweep away

Land masses and deep sky through empty air.

In fear of this, Jupiter hid them away

In caverns of black night. He set above them

Granite of high mountains – and a king

Empowered at command to rein them in

Or let them go.” (Book 1, Lines 75-89)

Thus: BLDGBLOG’s Aeolian Reef.

To be fair, this all began as nothing more than an idea for a new, artificial island that would be added to the Cyclades archipelago in Greece. It would be somewhere between Constant’s Babylonic mid-sea pavilion –

– the Maunsell Towers –

– and a kind of massive, off-shore, geotechnical saxophone.

Full of vaulted tubes and curved ampitheaters – and complex twists through a hollow, polished core – this modern Aeolia, an artificial island, would produce storms (and even, possibly, negate them).

A modern Aeolia, in other words, would be a “weather-breeding isle” – or a “weather-cancelling isle,” as the case may be: because then there was Katrina.

What would happen, I thought, if you built a manmade, weather-cancelling isle that could *stop hurricanes from forming*? I realized, of course, immediately, that you would actually need hundreds of these tuba-like, anti-hurricane islands – even an entire manmade archipelago of them – because the atmospheric paths of storms are far too unpredictable.

You would need, that is, an Aeolian Reef.

The Aeolian Reef – and the current author, who cannot draw, hint-hint, would *love* to collaborate with any BLDGBLOG readers who want to illustrate some of these things – would consist of oil derrick-like platform-islands built in climatologically influential patterns throughout both the Gulf of Mexico and the larger, equatorial Atlantic.

The Aeolian Reef would: 1) trap and redirect high-speed winds from any burgeoning tropical storms and hurricanes, thus preventing them from actually forming; 2) provide incredibly exciting meteorological/atmospheric observation platforms far out at sea; and 3) be readily exportable to other countries and other climates, for other purposes – land-based anti-tornado clusters, for instance.

This would therefore take the subject of an earlier BLDGBLOG post a few steps further: it would use architecture, or landscape architecture, as a way to directly influence, change, or redirect the climate.

It would, in short, be *landscape climatology*.

One could imagine alternative uses, of course; even a computer glitch or global supervillain who rearranges all the internal valves of the Aeolian Reef to generate the mother of all hurricanes… in which case the Reef would be something of a national security threat.

This thread continues in Katrina 1: Levee City (on military hydrology); and Katrina 2: New Atlantis (on flooded cities).

Katrina 2: New Atlantis (on flooded cities)

New Orleans is not the only city to be faced with a future of indefinite flooding – nor is it the only city in the world below sealevel.

The entire nation of the Netherlands, for instance, provides perhaps the most famous example of urbanized land reclaimed from the Atlantic seafloor. “Polders” is the Dutch name for such rigorously flood-controlled territory, and an exhibition literally even now being held at the Rotterdam-based Netherlands Architecture Institute explores the polders’ geotechnical creation.

The polders’ “rationally organized landscape is unique, but also vulnerable,” the NAI explains. Vulnerable to overdevelopment – as well as to catastrophic flooding.

The 2005 Rotterdam International Architecture Biennale, in fact, takes nothing less than “The Flood” as its central, organizing theme – with one particular sub-focus being Water City*.

[Image: The metropolis, the flood, the boundaries of architectural design.]

In April and May, 2005, The New Yorker ran a three-part article by Elizabeth Kolbert, called “The Climate of Man,” on the subject of human-induced climate change. The third part, published on 9 May 2005, ends with a description of how “one of the Netherlands’ largest construction firms, Dura Vermeer, [has] received permission to turn a former R.V. park into a development of ‘amphibious homes'” – a floating city. (The Guardian also has an article about this.)

“The amphibious homes all look alike,” Kolbert says. Floating on the River Meuse in Maasbommel, “they resemble a row of toasters. Each one is moored to a metal pole and sits on a set of hollow concrete pontoons. Assuming that all goes according to plan, when the Meuse floods the homes will bob up and then, when the water recedes, they will gently be deposited back on land. Dura Vermeer is also working to construct buoyant roads and floating greenhouses” – the entire human race gone hydroponic.

As Dura Vermeer’s environmental director says: “There is a flood market emerging.”

[Image: A floating house, moored to the earth, in Maasbommel.]

Further afield, the year 2005 has seen major flooding in Europe, India, and Bangladesh, to name but a few sites of major hydrological catastrophe.

In Mumbai, India, *The Economist* explains, the 2005 floods “uncovered long-term failures. Not enough had been done to maintain Mumbai’s ageing infrastructure, such as storm-drains and sewers. Worse, new building had weakened the city’s defences. Large areas of protective mangrove had been razed – in one notorious example, to make way for a golf course. Developers have built on wetlands, clogging natural drainage channels. River banks have been reclaimed and become slums.”

And then there is Bangladesh. “From the air,” we read, also in The Economist (most of their articles are for subscribers only, it’s really irritating), “Bangladesh looks less like a country than one vast lake, dotted with thousands of tiny islets, clumps of trees and houses. Few boats ruffle the placid floodwaters: there is nowhere to go.” And yet “[t]he great lake of Bangladesh is in reality a network of nearly 250 rivers.”

New Orleans, Rotterdam, Bangladesh, Mumbai: 2005 will be the year of flooded infrastructure and overwhelmed cities.

And so if Atlantis sets the gold standard for civilizations lost to floods – forget Noah – then it’s interesting that Atlantis, even before Katrina occurred, was back in the news this year (though I suppose it is every year). As already explored elsewhere on BLDGBLOG, Atlantis’s island home may (or may not) be in the Straits of Gibraltar.

The real issue, however, that the infrastructural possibility of Atlantis brings to the fore – or, rather, that Katrina brings to the fore, through the hydrological destruction of New Orleans – is revealed quite clearly in the following artist’s representations of what Atlantis might have looked like:

Atlantis, city of dikes and levees, city of canals and inland seas, city of water-smart urban design and hydrological planning – it, too, was swallowed by the oceans, and destroyed.

This thread continues in Katrina 1: Levee City (on military hydrology); and Katrina 3: Two anti-hurricane projects (on landscape climatology) – both on BLDGBLOG.

Katrina 1: Levee City (on military hydrology)

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

It’s too easy, not to mention slightly vindictive, to blame all of hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic impact and aftermath on the Army Corps of Engineers; but it is worth remembering that New Orleans – in fact the near totality of the lower Mississippi delta – is a manmade landscape that has become, over the last century at least, something of a military artifact. To say that New Orleans is, today, under martial law, is therefore almost redundant: its very landscape, for at least the last century, has never been under anything *but* martial law. The lower Mississippi delta is literally nothing less than landscape design by army hydrologists.

New Orleans as military hydrology.

Or, military urbanism as a hydrological project.

According to The Economist, “For much of the 20th century the federal government tampered with the Mississippi, to help shipping and – ironically – prevent floods. In the process it destroyed some 1m acres of coastal marshland around New Orleans – something which suited property developers, but removed much of the city’s natural protection against flooding. The city’s system of levees, itself somewhat undermaintained, was not able to cope.”

When even people within the Army Corps of Engineers began to warn that the hubristic landscape design methods of the US military might actually be inappropriate for what is a very muscular, flood-prone, not-to-be-fucked-with drainage basin, the warnings were taken – well, frankly, they were probably taken to be blatantly unpatriotic, knowing what’s happened to this country. But I digress.

“There is an irony,” The Economist elsewhere continues, “in this warning coming from the Corps of Engineers. Just as with the Everglades in Florida, New Orleans’s vulnerability has been exacerbated by the corps’ excellence in reshaping nature’s waterways to suit mankind’s whims. In the middle of the last century, engineers succeeded in re-plumbing the great Mississippi… [which simply] hastened erosion of the coastal marshes that used to buffer New Orleans, leaving the city needlessly exposed. Most of the metropolitan area lies below sea level on drained swamp land. Levees normally hold back the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain, but those were not designed to handle the waters that would come with such a powerful hurricane.”

Those same levees, in fact, as we all know, are actually now responsible for keeping the flood waters in:

“‘We’ve been living in this bowl,’ said Shea Penland, a coastal geologist who has studied storm threats to Louisiana for years,” in an interview with The New York Times. “‘And then Katrina broke channels into the bowl and the bowl filled. And now the bowl is connected to the Gulf of Mexico. We are going to have to close those inlets and then pump it dry.'”

But pumping the flooded city dry will be a “hard task,” according to the somewhat characteristic understatement of the BBC, in an article that then outlines the various steps of the engineering strategy involved (included new causeways, steel sheets, and 300-lb. sandbags).

But even if New Orleans is “pumped dry,” even if the city is eventually drained, even if commerce returns and the Big Easy’s population goes back to life as usual, there is still a much larger problem to face.

The Economist: “America’s Geological Survey has estimated that if nothing is done by 2050, Louisiana will lose another 700 square miles of coastal wetlands. Various local groups have long called for reconstruction of the marshes along the lines of the troubled $10 billion Everglades rejuvenation project. The New Orleans version, which would cost $4 billion more, would divert some 200,000 cubic feet of water each second from the Mississippi 60 miles through a channel to feed the existing marsh and to build two new deltas. The plan, which would also shut canals and locks to keep out salt water and would build artificial barrier islands, may find more adherents.”

Artificial barrier islands; 200,000 cubic feet of water each second; two new deltas: if at first you don’t succeed… try ever more elaborate feats of hydrological engineering. More of the disease is the cure for the disease. (See here for a much older – yet no less impressive for being small-scale – example of complex hydrological engineering).

Katrina, in this context, becomes a problem of landscape design.

The “hurricane” as an atmospherically-interactive, military-hydrological landscape problem.

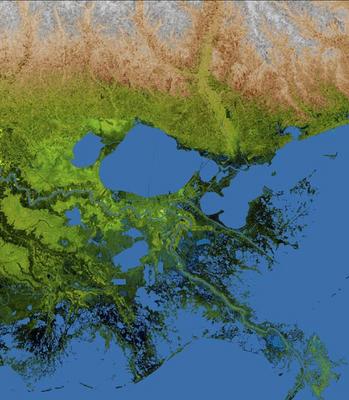

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

It’s a question, in other words, of human geotechnical constructions and how they interact with the complex dynamics of the earth’s tropical atmosphere and waterways.

[Image: Nearly all of the Atlantic’s equatorial reserves of warm water contributed to the strength of the storm. A few levees didn’t stand a chance.]

So what may soon become known as the destruction of New Orleans was simply the violent and undeniable clarification of how bad certain examples of landscape architecture really can be. This should surprise no one – horrify everyone, but surprise no one.

[Images: The total collapse of the manmade landscape has all but drowned the city, turning it, in the words of the Associated Press, into “a ruined city awash in perhaps thousands of corpses, under siege from looters, and seething with anger and resentment”; and the complete failure of urban infrastructure – including federal emergency response, management, and planning, which has hamstrung itself by sending first-responders to fight in Iraq – has made what is fundamentally a problem of landscape design much worse.]

[Images: The total collapse of the manmade landscape has all but drowned the city, turning it, in the words of the Associated Press, into “a ruined city awash in perhaps thousands of corpses, under siege from looters, and seething with anger and resentment”; and the complete failure of urban infrastructure – including federal emergency response, management, and planning, which has hamstrung itself by sending first-responders to fight in Iraq – has made what is fundamentally a problem of landscape design much worse.]

Financially, could things have been different? Could the money now being spent in Iraq and on bogus Homeland Security projects have gone elsewhere – into FEMA, for instance, or into hydrologically better-designed levee projects on the outskirts of New Orleans? Or into some of those “artificial barrier islands” mentioned above (that BLDGBLOG would love to help design)?

Yes, the money could have been spent differently. But is further entrenching a particular manmade landscape – really, a kind of prosthetic earth’s surface, a concrete shell, of valves, dams, locks, levees, and holding ponds installed upon the lower Mississippi – really the answer? Perhaps; but equally possible is that *there should not be a city there*.

As Mike Davis writes in *Dead Cities*: “Nature is constantly straining against its chains: probing for weak points, cracks, faults, even a speck of rust. The forces at its command are of course colossal as a hurricane and as invisible as a baccilli. At either end of the scale, natural energies are capable of opening breaches that can quickly unravel the cultural order. (…) Environmental control demands continuous investment and systematic maintenance: whether building a multi-billion-dollar flood control system or simply weeding the garden. It is an inevitably Sisyphean labor.”

Davis then describes the 19th century novel *After London: or, Wild England* by Richard Jefferies, a book in which “the medievalized landscape of postapocalyptic England” is explored “less [as] a nightmare than [as] a deep ecologist’s dreamwish of wild powers re-enthroned. (William Morris reported that ‘absurd hopes curled around my heart as I read it.’)”

After its destruction, then, this is London: “As fields, house sites, and roads were overrun, the saplings of new forests appeared. Elms, ashes, oaks, sycamores, and horse chestnuts thrived chaotically in the ruins while more disciplined copses of fir, beech, and nut trees relentlessly expanded their circumferences.”

The city is soon home to huge flocks of kestrel hawks and owls; wild cattle; and thousands and thousands of cats, “now mostly grayish and longer in body than domestic ancestors.” (As per the film *Logan’s Run* – or see CNN: “New Orleans residents who return to their homes [will] face ‘a wilderness’ without power and drinking water that will be infested with poisonous snakes and fire ants.”)

Eventually, Davis recounts, “new species or subspecies [evolve] out of other former domesticates, (…) [and] the monstrous vegetative powers of feral nature begin a full-scale assault on London’s brick, stone, and iron skeleton.”

“As marsh recovered the floodplain, (…) [t]he hydraulic pressure of the flooded substratum of the city – underground passages, sewers, cellars, and drains – soon burst the foundations of homes and buildings, which in turn crumbled into rubble heaps, further impeding drainage.”

A “200-mile-long inland sea” soon forms: “Jefferies’s extinct London, in short, is a giant stopped-up toilet, threatening death as an ‘inevitable fate’ to anyone foolish enough to expose themselves to its poisonous miasma.”

It becomes, that is, a flooded city.

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]

This thread continues in Katrina 2: New Atlantis (on flooded cities); and Katrina 3: Two anti-hurricane projects (on landscape climatology) – both on BLDGBLOG.